Ni Zan, Six Gentlemen, 1345, hanging scroll, ink on paper, 61.9 x 33.3 cm (Shanghai Museum; photo: Difference engine)

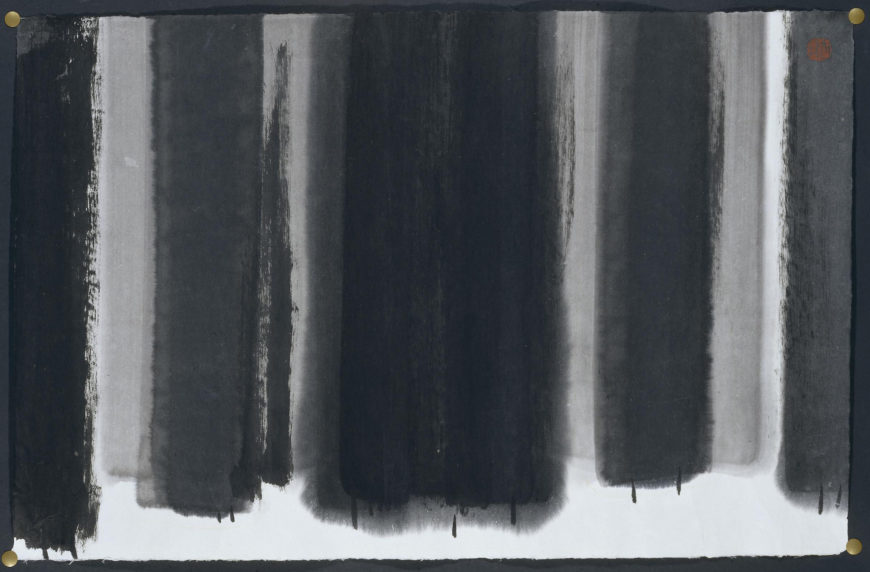

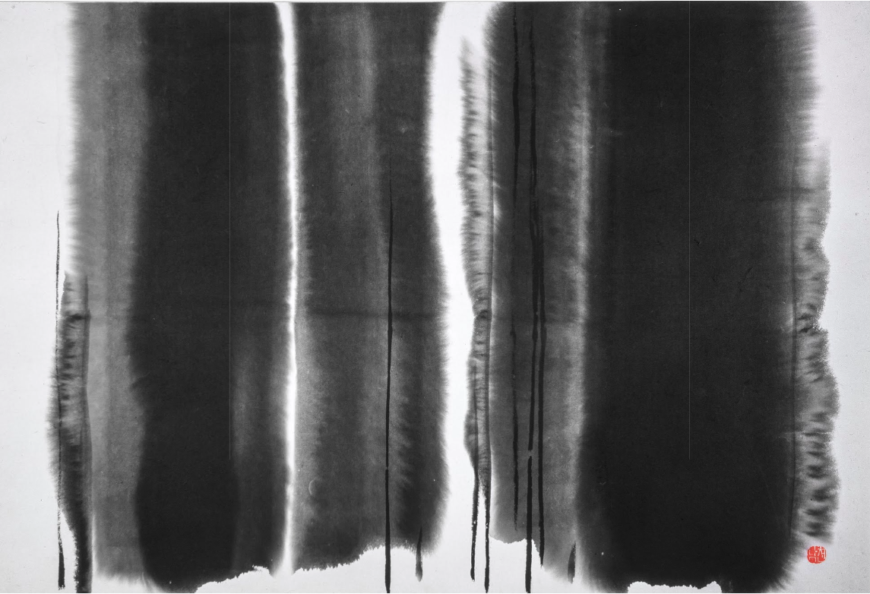

To choose the medium of ink on paper was important for the artist‚ a leader of Korea’s Sumukhwa or Oriental Ink Movement of the 1980s. Sumukwha is the Korean pronunciation of the Chinese word for “ink wash painting,” also called “literati painting.” The “literatus” can be defined as a “scholar-poet” or “scholar-artist,” a type of ideal man that emerged in China in the 11th century or before. Chinese poetry was considered the noblest art, and “ink wash painting” was its twin, because writing a poem and making a painting used the same tools and techniques—one resulting in words, the other a picture. In their simplicity and reductiveness, the style of ink wash paintings created centuries ago often seem to match Western notions of abstraction.

In Chinese poetry, mountainous landscapes and the plants that grow in them serve as metaphors for the ideal qualities of the literatus himself—qualities such as loyalty, intelligence, spirituality, and strength in adversity. The world the literatus wants to live in is one of beauty, deep in nature, away from the centers of power and money. These themes provided painters with a library of motifs. From the 1970s–90s, Song created many such landscapes, executed unconventionally, with and without titles. Summer Trees may also reference a traditional theme: a group of pine trees can symbolize a gathering of friends of upright character. Whatever his intention with this title, Song was clearly alluding to the special world of the literati. Highly educated and a respected professor, he stood among the modern literati of Korea.

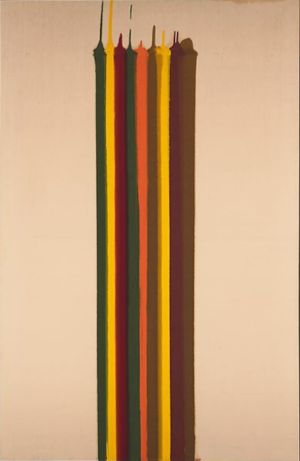

Song’s interest in abstraction and the formal properties of ink has led some art historians to attribute the inspiration for his work to that of American artists like Morris Louis, who used the medium of acrylic resin on canvas in his “Stripe” paintings of the 1960s, which resemble Song’s works of later decades such as Summer Trees. But in Korea during the 1980s, there was a tension between the influence of Western art that used oil paint (whether traditional or contemporary in style), and traditional Korean art that used an East Asian style, the vocabulary of traditional motifs, and the medium of ink for calligraphy and painting. Song felt very strongly that the materials and styles of Western art did not express his identity as a Korean.