It’s hard to imagine a time when we weren’t all posting photos on social media, sharing images of our vacations, meals, special occasions, or even constructing an online persona. In the 1970s, no such technology existed. But that doesn’t mean that images didn’t circulate. Or that they didn’t generate “likes” in their own way. Before the advent of Facebook or Instagram, the artist group Asco invented a novel way to freely circulate artwork to their friends and “followers”: the No Movie—photographs of ephemeral, often impromptu performances. Asco’s No Movies traveled across the world through the mail, projecting cinematic fantasy and evoking mystery. Provocative artworks in their own right, they were also part of an international network of artists that exchanged artwork through the mail, carrying Asco’s images to Europe, Latin America, and across the United States. As a No Movie, the photograph titled À la Mode is a sort of conceptual “post” before the advent of social media, and, as we’ll see, a photograph of a rather peculiar “meal.”

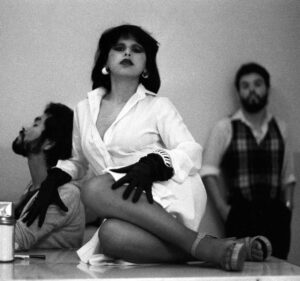

Harry Gamboa Jr., À La Mode, 1976, from the Asco era, performers (l-r): Glugio Gronk Nicandro, Patssi Valdez, Harry Gamboa Jr., printed 2010, chromogenic print, 32.4 x 47.6 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.) © 1976, Harry Gamboa Jr.

Nausea

Asco was an art group that originated in the early 1970s. Taking its name from the Spanish word for “nausea,” the group worked to convey the disgust, anger, and nausea they felt as young Chicanos growing up in East L.A. Inadequate schools, police brutality, the Vietnam War, and residential segregation were fixtures of their reality. They accordingly wanted to instill their disgust and nausea in the viewer. In fact, their name was taken from their first group exhibition entitled “Asco,” which was a collection of their “worst” works.

The group initially consisted of four people: Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk, Willie Herrón, and Patssi Valdez. Over the years, however, they enlisted a number of other collaborators. While they began working together to produce the artwork and illustrations for the Chicano-movement magazine Regeneración, their work would eventually encompass a range of media. They are perhaps best known, however, for their ephemeral actions, unauthorized public performance art, like Walking Mural (1972), Instant Mural (1974), or Stations of the Cross (1971), pieces that survive only through photographic documentation. While working collaboratively, they also all pursued individual projects including photography, printmaking, painting, and muralism.

No Movies

Some of their most unique and enduring creations were No Movies. These were photographic stills, circulated as phony press kits for movies that never existed. The group would devise a concept and pose for photographer Harry Gamboa Jr.’s camera, creating evocative scenarios that gestured toward cinematic narratives. Not coincidentally, the members of Asco were avid consumers of film. From the revolutionary art cinema of Jean Luc-Godard to low-budget B movies, the group found creative inspiration in the absurd, the sublime, and the unexpected. And Valdez recalls that her broader interest in photography, fashion, and self-styling also transformed her lack of resources into an emulation of Hollywood glamor: “I created personas of high fashion that I could not afford to buy or own, so I made up my own look, reinvented myself. I wanted to challenge the stereotypical images of Chicanas in the media at that time as well as our erasure from popular media.” [1]

As Valdez’s comments imply, Asco generally lacked the finances to make a film, despite their interest in cinema. The No Movies allowed them to project a concept for a film, to even evoke a set of associations for the viewer, who might then create in their imaginations a film that never existed. These works were a way for Asco to play creatively with cinema, but they were also a statement about the near impossibility of creating a grassroots Chicano cinema with meager resources. And they functioned as an implicit critique of Hollywood’s near exclusion of Chicanos. The No Movies were then a statement about a lack of means, access, and visibility. They were also an attempt to creatively overcome them. Harry Gamboa Jr. once explained that with No Movies “a multimillion dollar project could be accomplished for less than ten dollars and have more than 300 copies circulating around the world.” [2]

Mail artists

But for whom were these No Movies made? From the late 1960s to the 1980s, there was a vibrant, international network of mail artists that exchanged artwork through the postal service. Some artists tested the limits of what could be sent through the mail by sending unorthodox objects or sexually explicit content. What did all these artists have in common and why did they gravitate toward this medium? For a generation of avant-garde artists, many from marginalized communities, these informal networks were a way of bypassing art-world institutions such as museums and art galleries. It was an alternative means of creating, distributing, and experiencing art, and one that sought to remove barriers erected by money, formal education, and the gatekeepers of the art world. Mail art was generally inexpensive to produce and anyone could participate. And by the 1970s, the widespread availability of copy machines allowed artists to generate multiples cheaply. Not coincidentally, it was a practice embraced by many who found themselves entirely excluded from the mainstream art world, including Chicanos, political dissidents, and sexual minorities. Some of these mail artists are now recognized as important artists and collectives of the late 20th century: CUOM Transmissions in the U.K., the Fluxus group, General Idea in Canada, Clemente Padín in Uruguay, Ray Johnson in the U.S., and, of course, Asco and other Chicano artists like Teddy Sandoval and Gilbert “Magú” Luján.

Asco sent No Movies all over the world, usually emblazoned with a red “Asco” stamped on the photograph. As an extension of their No Movie project, they also orchestrated a clever parody of the Oscars: the Aztlán No Movie Awards. For this, mail artists, as No Movie creators, would be nominated in multiple categories, some of them clearly satirical. It is hard to imagine, for instance, how a piece of mail art could win an award for “Best Sound Design.” But this was also part of the evocative nature of No Movies, of allowing a viewer to construct an imaginary cinematic spectacle on the basis of a still image. Both emulating and skewering the pretensions of Hollywood, winners would be given a plaster cobra (purchased from a dollar store) that was spray-painted gold.

Figures (detail), Harry Gamboa Jr., À La Mode, 1976, from the Asco era, performers (l-r): Glugio Gronk Nicandro, Patssi Valdez, Harry Gamboa Jr., printed 2010, chromogenic print, 32.4 x 47.6 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.) © 1976, Harry Gamboa Jr.

This particular No Movie, À la Mode, features members Harry Gamboa Jr., Gronk, and Patssi Valdez. Striking a glamorous pose, Valdez occupies the center of the frame. Looking directly at the camera, she simultaneously exudes confidence and sensuality. But her deliberately composed position—reminiscent of fashion models—would seem to contrast with her environment. Closer inspection reveals that she is sitting on the table of a restaurant alongside a napkin dispenser and salt and pepper shakers. As it so happens, the photo was taken at Philippe in downtown Los Angeles, a local institution that claims to have invented the French dip sandwich. And according to Gronk, Valdez is portraying the scoop of ice cream atop a slice of pie. But why is she posing so dramatically in such a mundane environment? How are the other “characters” related to her or the space of the restaurant? Are they also portraying food or another aspect of the environment? Is there a story here or are the artists merely injecting a sense of cool defiance and glamor into their everyday surroundings?

While the image may inspire these questions (and others), it also refuses to provide clear answers. Even as a work of art, it eludes easy definition. Is the photograph the actual work of art? Or Is it instead only the photographic documentation of a collaborative performance work? Perhaps both? We could even imagine that the mail art exchanges and networks that Asco helped to sustain were also an artistic production of sorts. Almost 50 years later, these questions are difficult to resolve. While some would justifiably consider them collective works created by Asco, others argue that Harry Gamboa Jr. should receive sole credit for the photographic image. The answer to these questions ultimately depends on how we define No Movies as works of art.

Between standing or sitting

In some ways, this was part of the enduring impact and power of Asco. While using and commenting upon the built environment of Los Angeles, they also often refused to make meaning or to send a clear, uniform message. Gronk described the No Movies in aptly enigmatic terms: “Life/art standing and sitting repeatedly until you’re doing neither. The point between standing or sitting.” [3] In an era that often saw Chicano artists espousing specific causes or taking clear positions on political issues, Asco’s work often proved more ambiguous, even absurd. Perhaps this refusal inspired more “asco” and frustration than any other aspect of their work. But rage, confusion, and absurdity were part of their everyday realities, just as humor, glamor, and creative resilience were part of their artistic practice and a means of survival. And while somewhat misunderstood at the time, their work, as it fought against invisibility while circumventing mainstream institutions, is now understood as being just as political as it was conceptual. Their brand of conceptual art—embracing both absurdity and glamor, mixing genres and media, and prioritizing ephemeral action over enduring objects—continues to inspire new generations of artists.

Notes:

[1] Patssi Valdez, personal correspondence with author, August 1, 2023.

[2] Harry Gamboa Jr., Urban Exile: Collected Writings of Harry Gamboa Jr., edited by Chon A. Noriega (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), p. 28.

[3] Gronk quoted in Gamboa Jr. (1998), p. 30.

Additional resources

This work at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

C. Ondine Chavoya and Rita Gonzalez, Asco: Elite of the Obscure: A Retrospective, 1972–1987, exhibition catalogue (Williamstown and Los Angeles: Williams College Museum of Art and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2011).

C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz, Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., exhibition catalogue (Los Angeles: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries, 2017).

Harry Gamboa Jr., Urban Exile: Collected Writings of Harry Gamboa Jr., edited by Chon A. Noriega (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998).

David James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

Marci McMahon, “Self-Fashioning through Glamour and Punk in East Los Angeles: Patssi Valdez in Asco’s Instant Mural and À La Mode,” Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies, volume 36 number 2 (Fall 2011), pp. 21–49.

Carolina A. Miranda, “These ‘70s East L.A. Chicano Artists Are Having a Major Revival—But Infighting Threatens Their Legacy,” Los Angeles Times, May 5, 2023.

Chuck Welch, editor, The Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1995).

This essay is part of Smarthistory’s Latinx Futures project and was made possible thanks to support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.