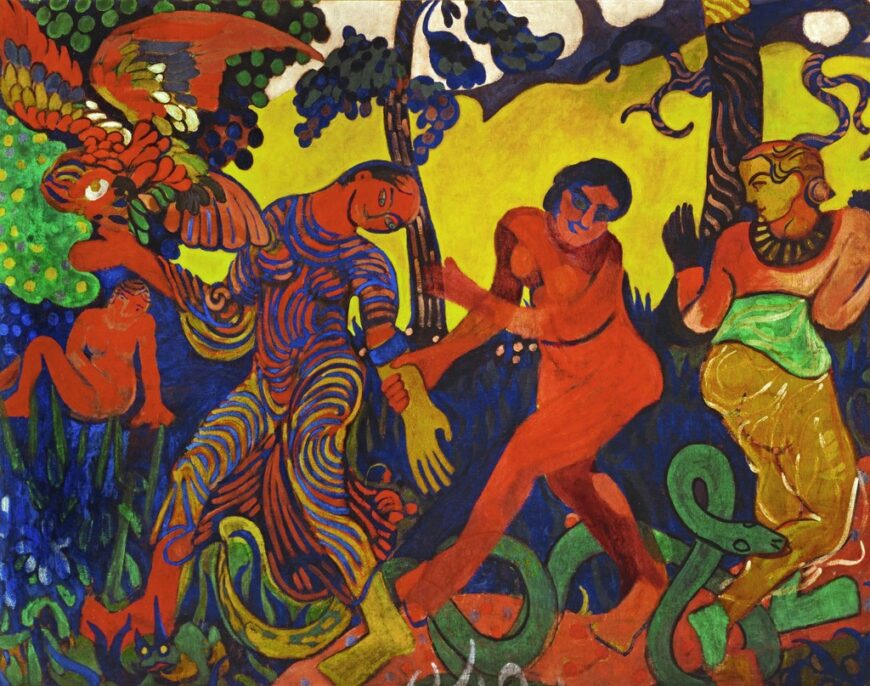

André Derain’s The Dance is an ambitious and remarkably eclectic painting that combines references to multiple European and non-European sources. The highly saturated palette of the primary colors (red, blue, and yellow), with the addition of the secondary green, is characteristic of Fauvism, a pictorial style associated with wild and unrestrained expression. In its attempt to synthesize a disparate collection of sources and references, The Dance testifies to the multi-layered, hybrid approach modern artists adopted as they attempted to create art works imbued with so-called primitive qualities.

Exotic and primitive motifs

At seven and a half feet wide, The Dance is as large as Henri Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre (Joy of Life), historically cited as a Fauve masterpiece, which was painted the same year. The subjects of the two paintings, female figures cavorting in an imaginary landscape, are similar, and both paintings suggest a fundamental union between humans and nature. Matisse’s references are, however, classical and Arcadian, while Derain’s are more exotic and primitive.

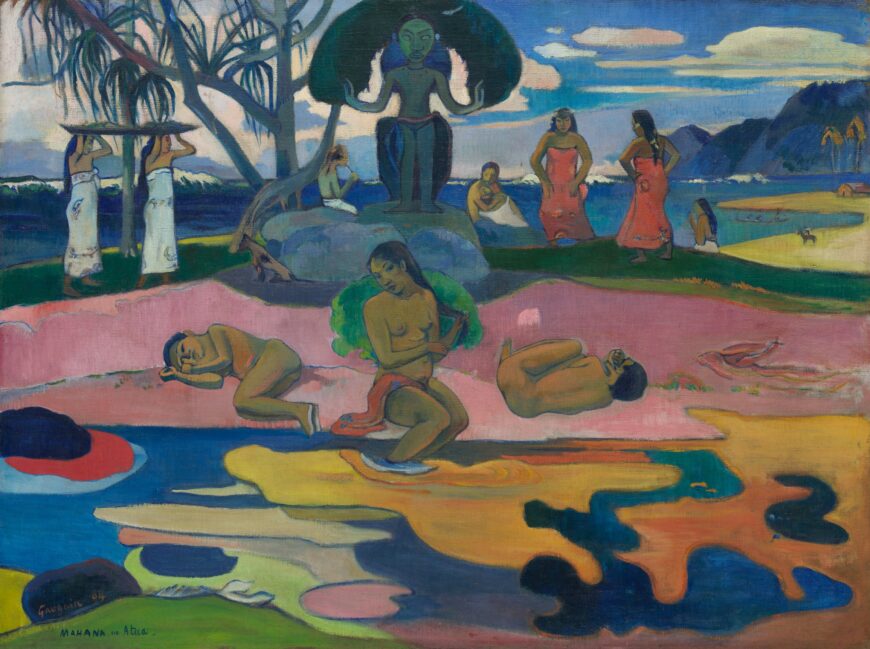

Paul Gauguin, Mahana no atua (Day of the God), 1894, oil on canvas, 68 x 91 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

The Dance echoes the paintings of Paul Gauguin in both style and subject matter. Like Gauguin, Derain uses simplified forms and unmodulated areas of bright color in a composition that emphasizes flat, decorative qualities. The subject is overtly exotic with nude and partially nude women displayed in a fantastic landscape along with a huge scarlet macaw and a green snake. These creatures allude to both their non-European native habitats and to an Edenic world where humans live in harmony with nature.

Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers, 1834, oil on canvas, 180 x 229 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Derain also followed Gauguin in his eclectic combination of cultural references. However, unlike his predecessor, whose primitivist pastiches resulted from a sincere commitment to the discovery of universal symbols and spiritual forms, Derain’s eclecticism is a more superficial adoption of varied exotic motifs. Art historians have identified references to Indian carved reliefs, African masks, Romanesque sculptures, European folk art, and Japanese prints in The Dance. The figure on the right is directly derived from another painting of “exotic” non-European women, Eugène Delacroix’s Women of Algiers. The Black woman on the right in Delacroix’s imagined harem scene has become a racially ambiguous, mostly nude blonde woman with multi-colored skin in Derain’s Fauve painting.

New and exotic forms of dance

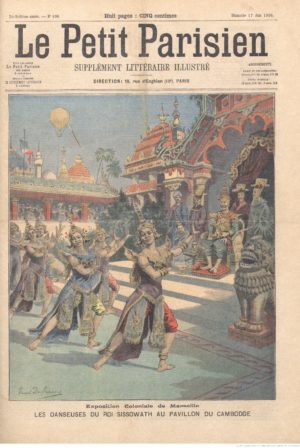

The Dance belongs to a well-established tradition of imagined primitivist scenes in European art that feature sexualized images of non-European women. It is also specifically of its time in its focus on dance. At the turn of the 20th century there was widespread interest in non-Western dance forms. International expositions often included performances of traditional court and folk dances from non-Western countries. Derain saw the Cambodian court dancers at the 1906 Colonial Exposition in Marseille around the time that he painted The Dance.

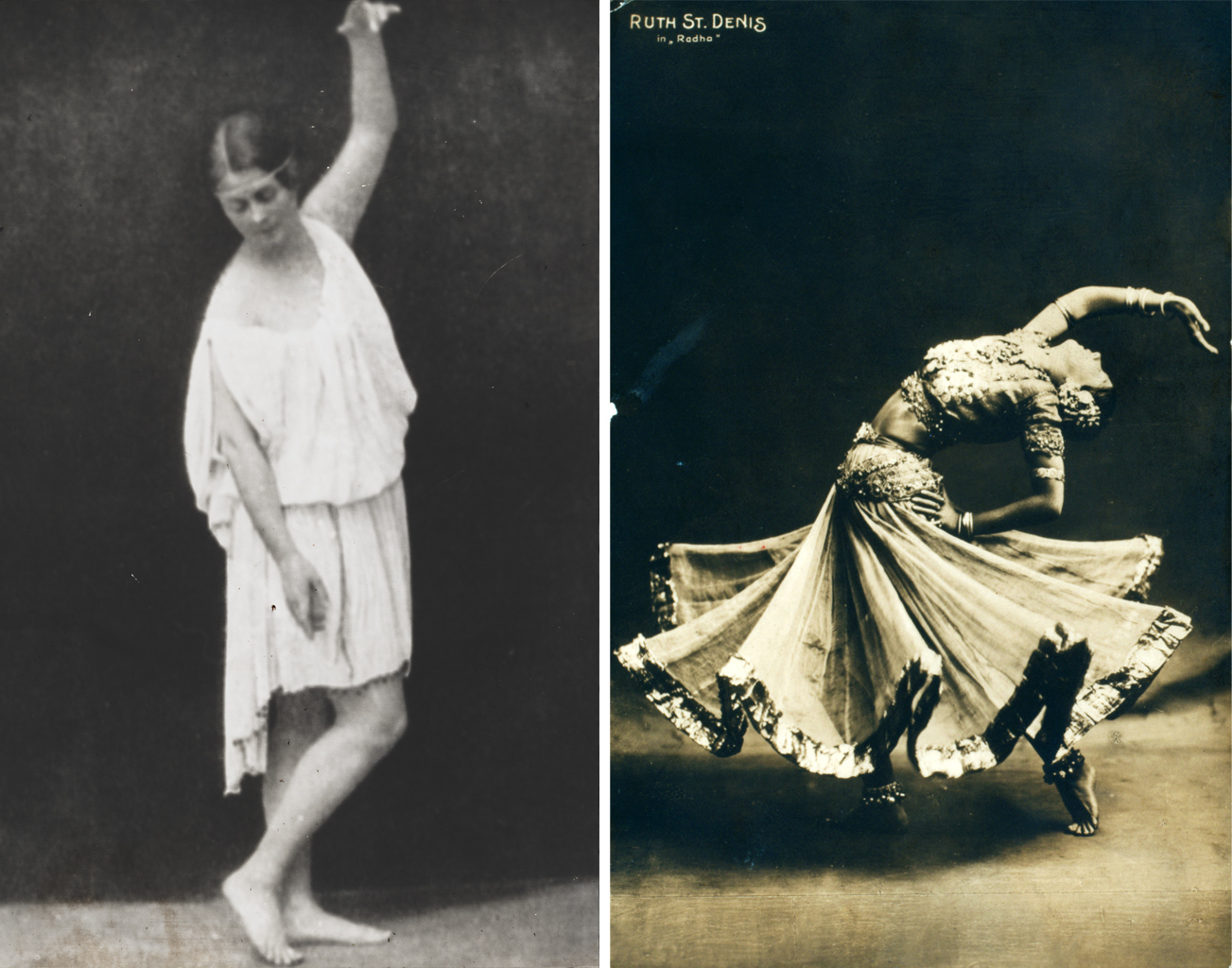

Modern dance also had its origins during this period. Dancers such as Loïe Fuller and Isadora Duncan rejected the stylized forms of classical ballet and focused on the body as a vehicle of direct, unfettered expression. Duncan saw her dancing as an expression of universal natural forces linked to Ancient Greece. Another popular dancer of the period, Ruth St. Denis, created “exotic” dances loosely based on Indian, Egyptian, and Babylonian mythology.

Left: Isadora Duncan dancing, 1903; right: Ruth St. Denis in Radha, c. 1906 (New York Public Library)

Fauvism and African art

Cultural eclecticism is a hallmark of European modern art in the early years of the 20th century, and Derain and his fellow Fauves Maurice Vlaminck and Henri Matisse were significant contributors to the trend. They were among the first modern artists to acquire African masks and sculptures, and Derain visited ethnographic collections in Paris and London to see non-Western artifacts. These became increasingly available for purchase during this period as a consequence of Europe’s escalating investment in its overseas colonies.

Women in nature with decoration (detail), André Derain, The Dance, 1906, oil on canvas, 175 x 225 cm (Fridart Foundation Collection)

With its combination of references to many different cultures and styles, Derain’s The Dance is a prime example of the period’s cultural eclecticism. Aggressive primary colors, simplified non-naturalistic forms, and an emphasis on decoration combines with eroticized images of women in nature to signify the primitive.

For many modern artists the use of intense colors and rudimentary forms was considered a means to regain contact with the natural energies of the universe and express themselves directly. Their appreciation of the non-Western works they collected was primarily formal (in other words, concerned with their appearance, and not their cultural context), and they adopted similar abbreviated and simplified forms in their own works.

Matisse remarked on the difference between the European approach to sculpting the human body and the African sculptures he saw in a Paris curio shop around 1905. European sculptors were interested in the naturalistic representation of musculature, while the African sculptures were “made in terms of their material, according to invented planes and proportions.” [1]

André Derain, Crouching Man, 1907, sandstone, 33 x 28 x 26 cm (Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna)

Primitivist styles and subjects

Both Matisse and Derain made sculptures of human figures that radically abstracted the body in response to the African sculptures they encountered. Derain’s roughly-carved sandstone Crouching Man simplifies and reduces the human figure to a cube, using exaggerated forms to convey a mood of introspective despair.

Matisse’s more conventional Reclining Nude also uses simplification and exaggeration of body parts, as well as twisting the angle of the head, to explore alternative strategies for representing the human figure.

Henri Matisse, Reclining Nude I (Aurora), 1907, cast in bronze c. 1912, 34.76 x 50.16 x 27.94 cm (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo) © Succession H. Matisse

Matisse’s painting The Blue Nude was developed from similar formal concerns. The traditional European subject of the reclining nude, often associated with Orientalist fantasies in the 19th century, is here situated outdoors in a vaguely exotic setting suggested by the palm-like plants in the background. As in Matisse’s sculpture, the shapes of the body are simplified and exaggerated to emphasize the buttocks and breasts.

Henri Matisse, Blue Nude (Memory of Biskra), 1907, oil on canvas, 92.1 x 140.3 cm (Baltimore Museum of Art)

Matisse’s materials—paint on canvas—are emphasized, as is the artist’s labor. We see his brushstrokes and, in places, the canvas underneath the paint. Matisse has not covered up changes he made to the figure, giving us the sense that we are seeing a work still in progress—further enhancing our awareness of the painting’s materiality. Subtitled Memory of Biskra, after a town in Algeria Matisse had visited, the painting is the result of an encounter between European erotic fantasy and abstracted forms derived from African sculpture.

In Blue Nude and The Dance, Matisse and Derain used a liberated Fauve approach to color and form to depict female figures in an exotic setting. They combined what was considered a crude and primitive style with references to so-called primitive cultures. The paintings demonstrate how closely the Fauve painters’ concerns were bound up with both primitivist fantasies of enjoying leisure and women in tropical landscapes and the formal qualities associated with primitivism—simplified drawing, flattened space, and bright decorative color.

Notes:

[1] Quoted in Sarah Whitfield, Fauvism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991), p. 161.

Additional resources