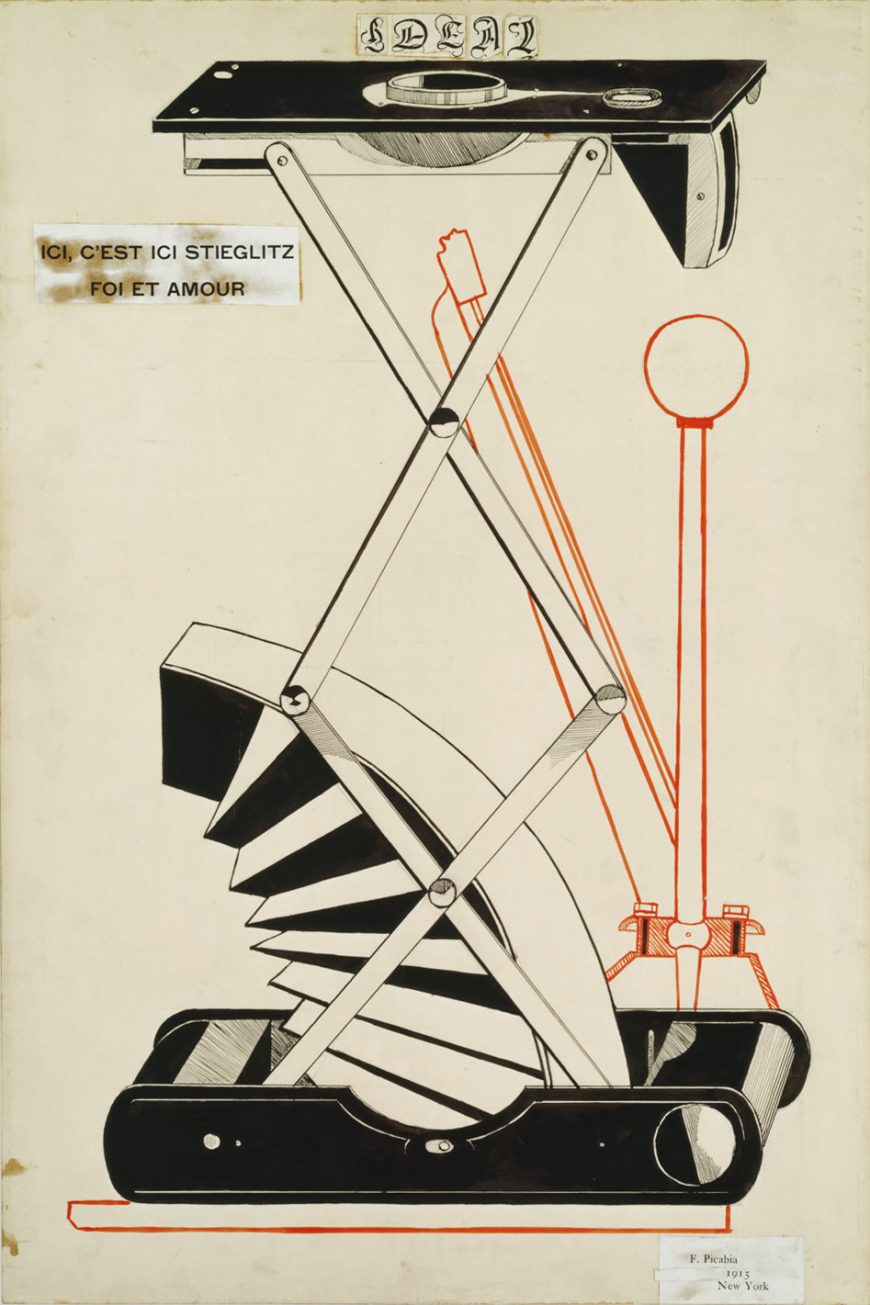

Francis Picabia, Ideal, 1915, ink, graphite, and cut-and-pasted painted and printed papers on paperboard, 75.9 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When you first see Francis Picabia’s Ideal, a mixed media piece consisting of drawing, painting, and cut and pasted letters, you might wonder, “Just what is this unusual contraption?” Despite the image’s reliance on a machine aesthetic (resemblance to sleek modern machinery that inspired many early twentieth-century artists) a closer look reveals that this is not a functional apparatus—at least, it would not function in any way we can easily identify. In this sense, the image undermines the whole point of technical drawings and modern inventions: to make life easier, not harder, for the people who use them.

Picabia’s industrial forms, inspired in part by his enthusiasm for technical manuals and diagrams, embrace the mechanical age. Yet the pictorial elements suggest dysfunction and when combined with its enigmatic captions, deflate any overblown pride that often results from technological achievement. If this resembles an image we might see in a catalogue, the machine being advertised has no known purpose. One could say, however, that the drawing calls attention to the radical rethinking of the status of art in the early twentieth century, an age of mechanical reproduction in which devices such as the camera showed the potential to replace the artist’s hand in the creative process.

New Forms for the Modern Age

The text Picabia included provides clues about his point in producing the image. Antiquated gothic letters at the top center of the picture spell the word “IDEAL,” a philosophical term referring to concepts and standards of perfection (such as ideal beauty) that were important to the Symbolist art movement at the turn of the twentieth century and, indeed, to much of the art produced in the west since the Italian Renaissance. Picabia had dabbled in the Symbolist style (which focused on dreams and personal visions) but, like many artists of his day, eventually turned instead to imagery more attuned to the modern age. In fact, for Picabia, the machine was the ideal form to communicate the new rush of sensations and possibilities that characterized modernity. He depicted odd combinations of machine parts in his art, however, to represent both human invention and fallibility—a combination that resonated in the context of World War I , which saw new technologies deployed, for the first time, in global warfare.

The tensions between utopic and dystopic views of modern machines play out in Picabia’s drawing, where he has rearranged and combined parts of a camera with what look to be an automobile brake and gearshift, forming something new, abstracted, and quasi-comical. The fact that this odd camera appears to be flipped onto its back and fitted with some kind of shifter might also allude to Picabia’s love of cars (he owned many and liked to drive fast). But the assortment of levers, accordion arm, and conveyor belt-like base could also suggest a heavy construction vehicle, the kind used to clear old structures from the sites on which modern skyscrapers are built. These towers of industry also attracted Picabia, who proclaimed, upon first seeing the New York skyline in 1913, that he would make art that speaks to “the rush of upward movement” and humankind’s “desire to reach the heavens, to achieve Infinity.” [1]

New York, new ideas

Using a wartime mission to obtain supplies in the Americas as a ruse, Picabia (who was French) travelled to New York in 1915 to escape the war. There, he reunited with friends he had made on his first trip to New York for the 1913 Armory show (the first large-scale exhibition of modern art in the United States). One of these friends was the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who was also a prominent gallery owner and patron of modern art in New York.

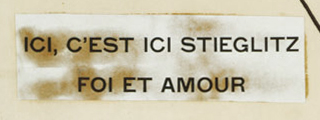

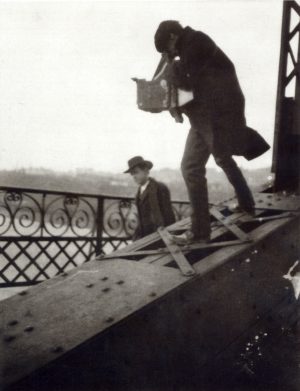

The caption at the upper left of the piece uses a modern typeface, and offers clues to the meaning of the image. It proclaims in French, “Ici, C’est Ici Stieglitz Foi et Amour” (“Here, Here is Stieglitz Faith and Love,” usually translated as “Here, This is Stieglitz Here”), and tips us off that what we are looking at is actually a kind of portrait. Instead of a naturalistic rendering of Stieglitz, Picabia represents the photographer as a hybrid machine made from a large camera not unlike the one the photographer was known to have carried to photograph the New York cityscape.

Alfred Stieglitz Photographing on a Bridge, c. 1905, gelatin silver print, 10.3 x 7.9 cm (source)

Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 in New York served as a nexus of activity for photographers and the few modern artists practicing or exhibiting in the United States at that time, and Picabia showed his work there in 1913 and 1915. He also became involved with gallery activities and even contributed to the journal titled 291 that Stieglitz and his cohorts published, featuring Ideal on one of its covers.

With the artistic encouragement of Stieglitz and the group of artists, photographers, and writers at Gallery 291, Picabia made a series of mechanical portraits, including Ideal, that he called “Mechanomorphs,” creating a veritable who’s who symbolized by a readymade vocabulary of machine parts and plans. In each of these mechanical portraits, Picabia used elements gleaned from advertisements and technical manuals to represent key features of his sitters. To depict Stieglitz, the rendering comprised of camera parts seemed ideal. The title ‘Mechanomorph” seems fitting for the piece as well, since it combines machine parts and suggests shifting, ambiguous functions. Yet, this camera appears to be broken and may signify a growing tension between Picabia and the photographer.

Cover of 291 journal featuring Picabia’s Ideal, 1915, relief print on paper, 44 x 28.9 cm (National Portrait Gallery)

A mechanical riddle

Flipped on its back, an accordion arm raises its lens (or eye) upward, an image in keeping with the idealism Picabia saw in Stieglitz’s circle promoting modern art in New York. It was an idealism that Picabia shared, to some extent, but rejected in his embrace of the Dada movement—an international collection of artistic approaches that seemed worlds away, yet also in close physical proximity, to 291. Dada is a nonsensical term loaded with connotations about the joys of youth and the idiocy of the absurd that was characterized by an ironic stance in relation to culture and especially to any of the traditions that had led to the war. Along with his friend Marcel Duchamp, who had also fled the war in Europe, Picabia became a leader of the Dada movement in New York, where he combined enigmatic, absurd, yet witty imagery that often featured texts that read like riddles. Ideal is perhaps one of the most intriguing of these riddles, referring, in its way, to Picabia’s exploration of the relationships between human beings, machines, and creativity.

1. Francis Picabia, statement made to the New York Times, February 16th, 1913 (“Picabia Art Rebel, Here to Present the New Movement,” section V, p. 9).

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cover of 291 featuring this work at the National Portrait Gallery

Maria Lluisa Borràs and Francis Picabia, Picabia (New York: Rizzoli, 1985).

Leah Dickerman and Brigid Doherty, Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris (Washington [D.C.]: National Gallery of Art in association with Distributed Art Publishers, New York, 2005).

Francis Picabia, Statement made to the New York Times, February 16th, 1913 (“Picabia Art Rebel, Here to Present the New Movement, ” Section V, p. 9).

Francis Picabia, Statement made to the New York Tribune, October 24th, 1915 (“French Artists Spur on American Art”).

Francis Picabia, William A. Camfield, Beverley Calté, Candace Clements, Arnauld Pierre, Pierre Calté, and Imogen Forster, Francis Picabia catalogue raisonné (Brussels: Mercatorfonds, 2014).

William A. Camfield, Francis Picabia (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1970).