Otto Dix, Dr. Mayer-Hermann, 1926, oil and tempera on wood, 58 3/4 x 39 inches (MoMA)

Jan Gossaert, Portrait of a Merchant, c. 1530, oil on panel, 25 x 18 3/4 inches (National Gallery of Art, Washington)

Otto Dix painted the successful Berlin throat specialist Dr. Wilhelm Mayer-Hermann surrounded by medical equipment in his own examination room. Wearing the white smock and head mirror of his profession he stares straight out of the painting at us. The reflective globe of a machine used for light treatments seems to be part of his head and intensifies our sense of being under close observation.

Just as we are being observed by the doctor, we are observing him. Dix painted Dr. Mayer-Hermann using a painstaking, realistic technique, showing us that Dix himself carefully studied the doctor and his surroundings. Both the realistic style and the medium (oil and tempera paint on a wood panel) are old-fashioned and consciously imitate the highly-refined portraits of Northern Renaissance painters. In Portrait of a Merchant, Jan Gossaert depicted the 16th-century merchant surrounded by the tools of his trade, just as Dix does in his portrait of the 20th-century throat specialist.

The convex reflective surface of the light machine above the doctor’s head shows us a distorted image of the rest of the examination room. Dix is here quoting another very famous Renaissance painting, Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, in which a convex mirror similarly reflects the room in front of the depicted figures.

Left: Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait, 1434, oil on panel, 82.2 x 60 cm (National Gallery, London); right: Otto Dix, Dr. Mayer-Hermann, 1926, oil and tempera on wood, 58 3/4 x 39 inches (MoMA)

Realism and abstract forms

The meticulous realism used in Renaissance portraits by van Eyck and Gossaert reveals a world of deep colors and rich, soft textures that is very different from the metal machinery, hard tile surfaces, and dirty white, grays, and browns of the modern doctor’s examination room. In addition, the flat composition shows Dix’s modernist concern with abstract geometric form. The doctor is centered in the painting, framed by the metal structure of the machine on the right and the hanging electrical cord on the left. Seated in a symmetrical pose that emphasizes his rotundity, he is positioned squarely in front of a flat wall covered in a grid of tiles. Above his curved shoulders various mechanical objects create a repeating pattern of circles that echoes his round torso and face. The effect is both humorous and ominous.

A critical attitude

Dix was a leading representative of the realist tendency in post-World War I German art known as Neue Sachlichkeit, usually translated as New Objectivity. The name of the tendency originated in a 1925 exhibition of figurative painters that included Dix, George Grosz, and Max Beckmann. Some of the painters associated with Neue Sachlichkeit had previously been associated with German Expressionism or the Dada movement and maintained a critical attitude toward modern Germany. Dix abandoned his early Expressionist style to paint what he saw as a corrupt contemporary German society with a pitiless “objective” eye.

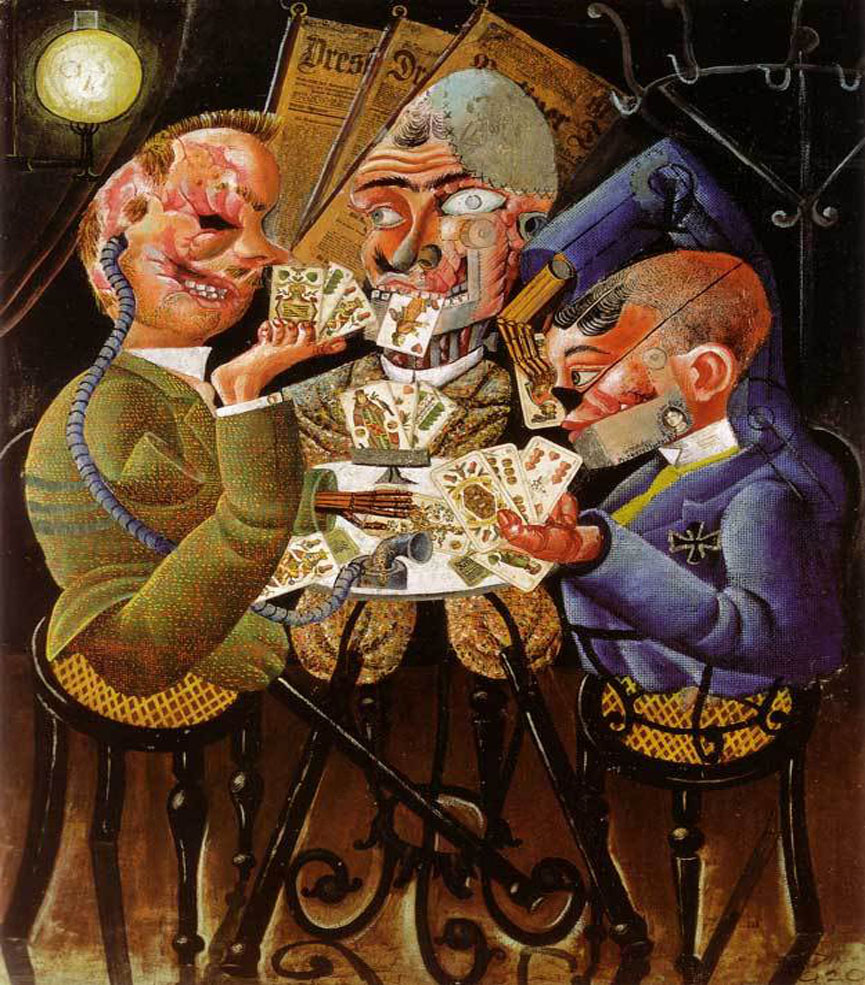

Otto Dix, The Skat Players — Card-Playing War Invalids, 1920, oil and collage on canvas, 110 x 87 cm (Nationalgalerie, Berlin)

In The Skat Players Dix depicted disabled war veterans in excruciating detail. The combination of collage and oil paint he used in this work reflects early plastic surgery (first practiced on a mass scale in World War I), which was often unsuccessful and extremely disfiguring. Dix shows the veterans enjoying a card game together despite their severe physical mutilations.

Otto Dix, Sylvia von Harden, 1926, oil and tempera on wood, 121 x 89 cm (MNAM, Pompidou Center, Paris)

Dix also painted successful members of German society in unflattering, even caricatural ways. He depicted the writer Sylvia von Harden as an androgynous “new woman” — a then-popular term for the modern, sexually-liberated woman. She seems vaguely menacing with her gesturing, over-large hands, lit cigarette, and black-rimmed monocle. Posed to emphasize the sharp angles of her head and body, and dressed in a boldly-patterned red and black check dress, she clashes with the traditionally feminine curves of the table, chair and glass, as well as the pink walls behind her.

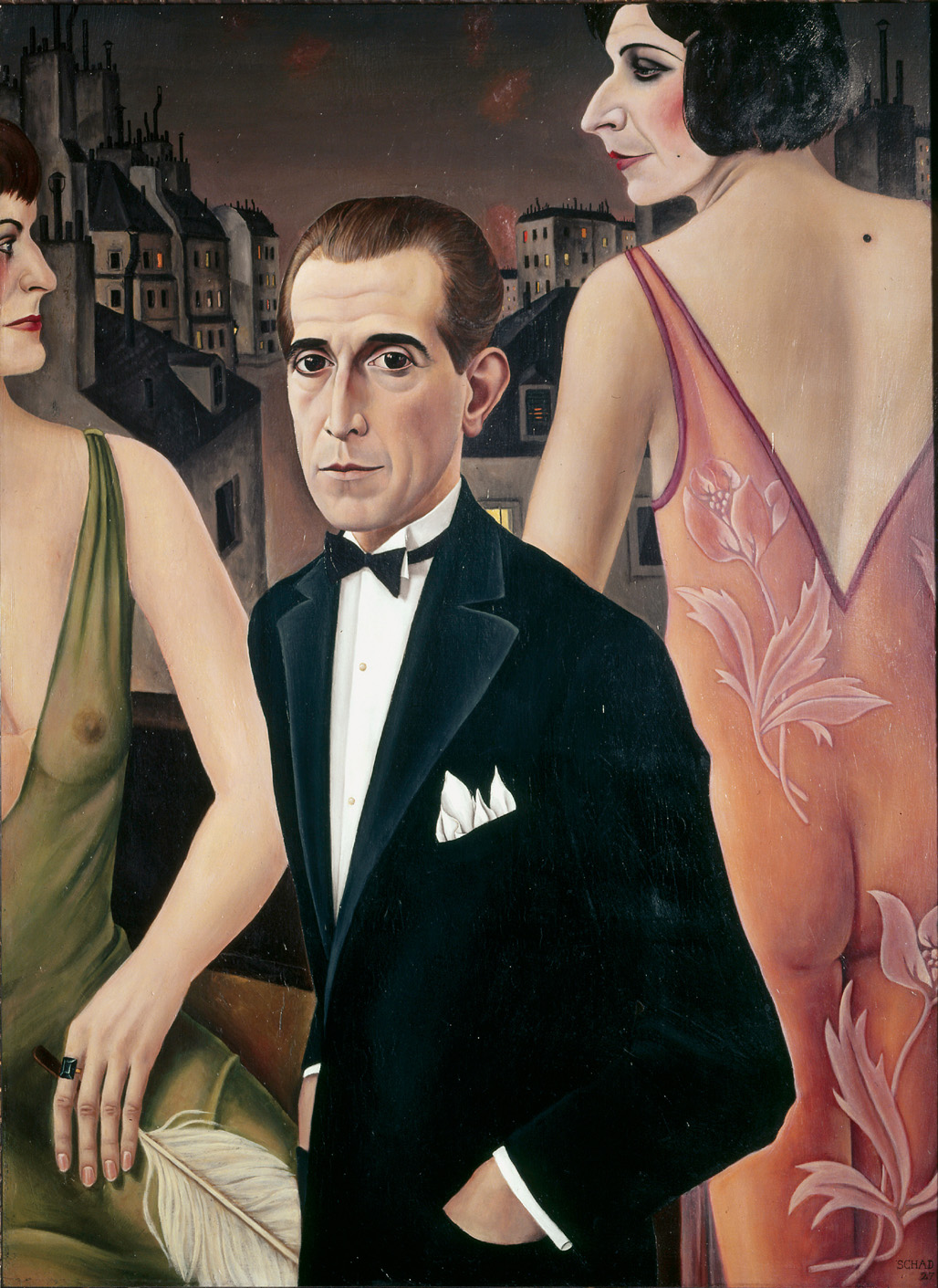

Christian Schad, Count St. Genois d’Anneaucourt, 1927, oil on panel, 86 x 63 cm (MNAM, Pompidou Center, Paris)

Christian Schad, previously associated with the Dada movement, was another artist associated with Neue Sachlichkeit who adopted a meticulous realistic painting technique. His portrait Count St. Genois d’Anneaucourt depicts the subject as part of a decadent bohemian world. Standing on a balcony with a Paris skyline in the background, the Count is dressed in an evening jacket and black tie. He looks out at us while two large, rather masculine-looking women in transparent dresses lock gazes behind him. In fact, the heavily made-up figure on the right was a cross-dresser from the Eldorado cabaret in Berlin, adding to the sexual tension created by the figures’ transparent dresses and challenging stares.

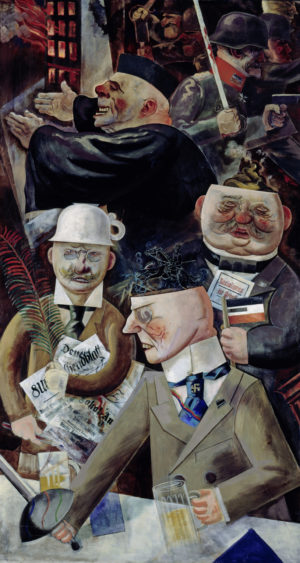

George Grosz’s Pillars of Society uses caricature to condemn the ruling classes of Germany’s Weimar Republic. In the foreground, a member of the old aristocracy, holding beer mug and sword, sports a Nazi swastika pin on his tie. The top of his head is cut off to reveal his outdated dreams of military triumph on horseback.

Rising behind him are a journalist (wearing a chamber pot on his head), a politician (with a pile of excrement in his head), a church minister (with his arms out to embrace the burning city), and helmeted soldiers, one carrying a bloody sword and gun. Here, Neue Sachlichkeit can be seen as more an attempt to reveal the truth about the ruling classes in a direct manner than a realistic style of painting.

Grosz did occasionally use the realist style most often associated with Neue Sachlichkeit. In a portrait of the writer Max Hermann Neiss, Grosz emphasizes his friend’s large head and hands and coldly records their wrinkles, veins, bone structure, and tonal variations. The brightly flowered cushions create a marked contrast to the frail figure dressed in his black suit and slumped down in the chair. This is a portrait in which it would seem objective truth takes precedence over affection for his friend.

Exposing the corruption of society

Max Beckmann participated in the original Neue Sachlichkeit exhibition in 1925 and is considered an important representative of the tendency, although his painting remained generally expressionist in style through the 1920s. Beckmann’s subject matter was also often highly personal, idiosyncratic, and allegorical rather than an objective depiction of reality. He is, however, similar to other Neue Sachlichkeit painters in his dedication to exposing the corruption of modern society, which he saw in terms of the spiritually fallen condition of humanity.

Max Beckmann, The Night, 1918-19, oil on canvas, 133 x 153 cm (Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf)

The Night is a claustrophobic scene of seven people crammed into a small space. Violence and torture are illuminated by a large burning candle in the foreground, while the window in the background opens onto black night. On the left a man in a nightshirt is being hanged with a scarf. Another man with a bandaged head squats barefoot on a table and smokes a pipe while he twists the arm of the hanged man. On the right we see a woman with her hands bound and her legs split apart. She appears to have been violated; her corset hangs open to reveal her bare torso and buttocks, her red stockings slide down, and she is only wearing one shoe. A girl is being carried upside down by a man wearing a cap pulled down over his eyes. He reaches behind himself to lower a blind over the window. Although the painting has been interpreted in relation to contemporary events, it is an image of human brutality and degradation that takes no explicit political stand.

The German Neue Sachlichkeit painters lived through the violence of World War I and its aftermath. Their art reveals the disillusionment and cynicism that resulted from their often psychologically-shattering experiences. The political upheavals of the post-war period and the brief economic boom of the 1920s were reflected in their paintings, which depict German society and its people as decadent and corrupt.