Robert Colescott, I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees De Koo, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 213.36 x 167.64 cm (The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University)

Robert Colescott’s massive painting, I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees De Koo, vibrates with vigorous brushstrokes in brightly saturated colors—peachy pinks and seafoam greens crash into patches of coral, teal, yellow, and gestural black marks. Standing close to the painting allows it to dissolve into abstract form but stepping back reveals a female figure wearing a kerchief on her head, her brown skin adorned with pastel pink cheeks and glossy lips.

On the surface, Colescott’s painting is a parody of Woman I, the most famous work by Abstract Expressionist painter Willem de Kooning—the “de Koo” of Colescott’s title. De Kooning was a dominant figure in American art when Colescott parodied his work—he was known for his innovative use of paint and fusion of figuration and abstraction.

Parodies that reflect on race, gender, and art history

Colescott is most well-known for a series of parodies he began in 1975 that use a similar tactic to I Gets a Thrill Too—he repainted canonical European and American paintings but changed some or all of the figures into racist caricatures of Blackness. For example, he repainted Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434), and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). These works ask us to reflect on the way stereotypes about race and gender communicate, and to think about what kind of stories they tell, in both popular culture and art history.

Left: Robert Colescott, Natural Rhythm: Thank You Jan van Eyck, 1976, acrylic on canvas (Collection of Robert H. Orchard, St. Louis, Missouri); right: Robert Colescott, Les Desmoiselles d’Alabama: Vestidas, 1985, acrylic on canvas, 96 x 92 in. (Seattle Art Museum)

Critics often discuss de Kooning’s Woman I as a painting about the images of women that circulated in the 1950s, an image shaped by widespread gender inequality and sexist stereotypes (discussed more below). Colescott’s parody of Woman I complicates de Kooning’s image of women by highlighting the different ways that white and Black women are (mis)understood and discriminated against in a patriarchal society such as the United States. Colescott’s work underscores the idea that de Kooning’s Woman I is not a universal woman, but a white woman. In contrast, Colescott’s painting asks, what are the implicit messages about Black womanhood embedded in American visual culture?

The philosopher king

De Kooning’s prominence in the mid-century art world made him a loaded figure for emerging painters in the 1970s—he was both a role model of avant-garde innovation and an oppressively famous “father figure” to painters like Colescott. By the late 1970s, when Colescott painted I Gets a Thrill Too, de Kooning had become a kind of contemporary “old master.” Case in point—in 1972, The New York Times, art critic Peter Schjeldahl crowned de Kooning the “philosopher-king” of contemporary painting and declared, “few younger painters are any longer being misled by his example into thinking that because they have a sense of what he’s doing, they can do it too. There can be only one de Kooning, and by now, everybody knows it.” [1] While critics like Schjeldahl lauded de Kooning’s innovation, some feminist scholars accused de Kooning of outright misogyny. For critic Carol Duncan, de Kooning was typical of the so-called “geniuses” of avant-garde art in his presentation of women as monstrous and loathsome sexual objects. [2]

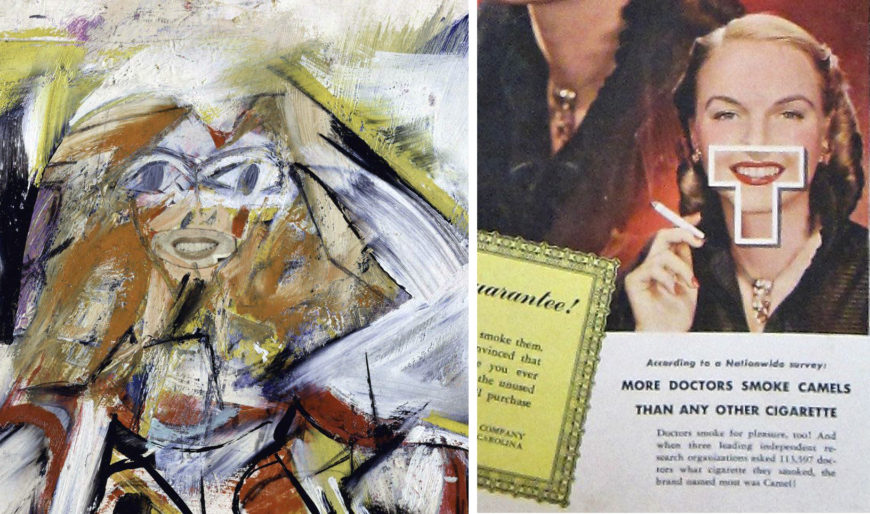

Left: detail of Willem de Kooning, study for Woman I, 1950, oil, cut and pasted paper on cardboard, 37.5 x 29.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: T-Zone, detail from Camel cigarette ad, back cover of Time Magazine, January 17, 1949.

Robert Colescott, I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees De Koo, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 213.36 cm x 167.64 cm (The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University)

Like Colescott, de Kooning looked to both art history and popular culture as models for his work. Woman I was inspired by archetypal images of women, from ancient fertility figures and Renaissance-era madonnas to pin-up girls and Hollywood bombshells. In early studies for his version of Woman I, de Kooning experimented with facial and anatomical elements cut directly from advertisements, such as lips and teeth meant to make cigarettes seem healthful and sexy.

If de Kooning’s Woman I shows a woman who is both alluring and terrifying, Colescott’s I Gets a Thrill Too does something startlingly similar. In I Gets A Thrill Too, Colescott also looks to the representation of women on product packaging. Colescott’s revised woman appears to be a “mammy” figure—a racist trope embodied most famously by the syrupy sweet brand icon, Aunt Jemima. Colescott’s mammy smiles, but her smile seems a bit tentative, and her eyes have a sidelong gaze.

The “mammy” archetype derives from 19th-century depictions of enslaved older women, who were often tasked with the most intimate forms of labor, such as rearing children, cooking, and managing their enslavers’ households.

“Old Aunt Jemima” was originally a song sung by enslaved field workers, adapted and sung countless times during minstrels shows by white (and usually male) performers in blackface makeup and drag. Cultural studies scholar Michele Wallace describes how the mammy symbolized a paradoxical combination of opposites—she was both comforting and monstrous, complicit and rebellious. [3] Colescott’s mammy figure is both adorable and grotesque, her cartoony smile made unsettling by the way her head seems to float, disembodied in the picture plane.

Willem de Kooning, Woman I, 1950–52, oil on canvas (MoMA) ;right: Robert Colescott, I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees De Koo, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 213.36 x 167.64 cm (The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University)

Looking at Colescott and de Kooning’s paintings side by side reveals some of the subtle aesthetic differences between the two. In I Gets a Thrill Too, Colescott emphasizes flat, cartoonish planes of color in his mammy’s face by juxtaposing them with the more expressionistic marks used by de Kooning. Where de Kooning had applied layer upon layer of oil paint in muddy tones, adding and subtracting paint by scratching at the surface, Colescott has filled in thin patches of brightly colored acrylic. Colescott’s graphic style resonates with the tactics of Pop Art by alluding to American product packaging, where the mammy stereotype continued to be seen in the 1970s.

Who gets a thrill?

The title of Colescott’s painting requires a little extra context to unpack. Try reading “I Gets A Thrill Too When I sees de Koo” aloud to get a better sense of its sound. Colescott modeled this linguistic style after white renditions of Southern Black speech found in pre-Civil Rights era media such as Mark Twain’s novels or advertisements for Aunt Jemima’s maple syrup. While African Americans did not actually speak in a significantly different accent than white Southerners, writing their voices in so-called “dialect,” as if they were speaking a foreign language, was a dominant convention of literature intended to express the otherness of enslaved (and formerly enslaved) people. While some Black writers, such as Zora Neale Hurston and Claude McKay, used dialect in their story-telling—this linguistic form was controversial among the Black literati because of its strong link to the tradition of Blackface minstrelsy. [4] The phrase “de Koo” in Colescott’s title, when spoken aloud, seems to suggest the derogatory slur “coon.”

Colescott’s title has another intriguing element—the word “too.” If he gets a thrill too when he sees “de Koo,” who got the first thrill? Earlier in 1978, Colescott participated in an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art called “Art about Art,” which surveyed the phenomenon of contemporary American artists who were copying, reproducing, and altering images from art history in bold, unprecedented ways. The exhibition exposed Colescott to several parodies of de Kooning, including one by an artist named Mel Ramos, I Still Get a Thrill When I See Bill #3.

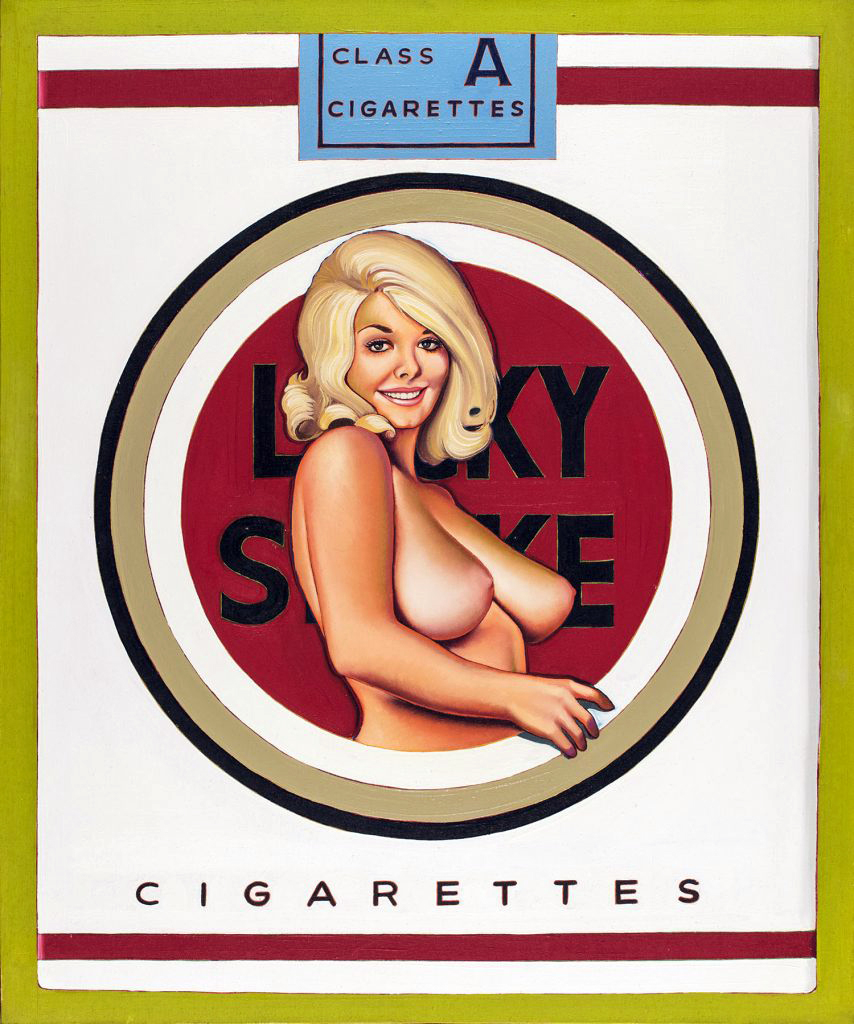

Mel Ramos, I Still Get a Thrill When I See Bill #3, 1977, watercolor on Paper, 301/2” x 22 1/2” (Collection of Mr. and Mrs James S. Morgan, Prairie Village, Kansas)

In Ramos’s version of Woman I, the artist mimicked the body of de Kooning’s figure in rough strokes, but replaced her head with a glamorous blonde bombshell. Ramos didn’t usually paint like de Kooning but instead made slick, seductive images of women posing evocatively with consumer products.

Ramos’s paintings draw on the style of vintage pin-ups, Hollywood posters, and pulp magazines. They push advertising imagery from implicit to explicit sexuality with slick images of beautiful, flirtatious women and mass-produced American commodities, as in his work Lucky Lulu Blonde. Ramos’s paintings of women posing with commodities are both objectifying and potentially subversive—they highlight the way that marketers use sexual desire to drive consumerism while also reveling in that desire. Ramos’s parody of de Kooning’s Woman I seems to mock de Kooning’s objectification of women, but also participate in it with his own style.

But, as Ramos’s title indicates, the painting was the third iteration in his “I Still Get a Thrill When I See Bill” series, which includes more than twelve works. Ramos’s I Still Get a Thrill When I See Bill #1, the first of these paintings, is a devoted brushstroke for brushstroke reproduction of de Kooning’s original Woman I. As he explained,

I was just really troubled by Willem de Kooning’s paintings at one time. So it was quite a challenge for me actually to try to attempt to do that painting just sort of outright, blatant, straightforward—here’s Woman No. 1—and still make it, you know, a Ramos painting . . . it was the kind of thing that I was doing with that painting, that is, the involvement with the paint itself, the painting of brushstrokes, the reconstituting of those brushstrokes, painting them visually the way they appear in magazines, as opposed to the way they actually appear on the paint, on the surface, which has nothing to do at all with the way they appear in magazine. Mel Ramos [5]

In one sense, the title “I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees de Koo,” may be the voice of the mammy figure, who gets a thrill, just like de Kooning’s female figure. In another sense, perhaps the title is a reference to Colescott, who, like Ramos, is thrilled by the legacy of de Kooning’s work even as he makes fun of it. To this day, African American art is often sidelined by mainstream narratives of art history, as if Black artists worked in a vacuum, without being influenced by artists of other races. Colescott’s parody of de Kooning emphasizes that he, too, is following in de Kooning’s footsteps as a participant in the ongoing progression of American avant-garde painting.

Installation view, Colescott and Ramos’s de Kooning parodies (photo: Deborah Barlow). Left: Robert Colescott, I Gets a Thrill Too When I Sees De Koo, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 213.36 cm x 167.64 cm (The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University); right: Mel Ramos, I Still Get a Thrill When I See Bill #1, 1976, oil on canvas, 203.2 x 177.8 cm (The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University)

Ramos and Colescott’s dual parodies now live together in the collection of the Rose Museum at Brandeis University. Together, they offer an opportunity to reflect on appropriation, the creative act, and the way images of women circulate through art history and popular culture.