Pablo Picasso, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, oil on canvas, 39 9/16 x 26 9/16 inches (Art Institute of Chicago)

Over a hundred years after it was made, Pablo Picasso’s portrait of his art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler remains a mysterious painting. Viewers often wonder if they are looking at it correctly. Is there an angle of view from which the rudimentary shadowy forms will suddenly fall into place and clearly reveal the image of a man? The answer is no, or at least not in the way that optical puzzles often reveal their subjects.

Pablo Picasso’s and Georges Braque’s Cubist paintings can, however, be deciphered. To help us understand the portrait of Kahnweiler we will look at how Picasso’s representation of the human figure changed from emphasizing solid forms to a more linear schematic approach in which the boundaries between figure and space dissolve.

Abstracting solid mass

Although the objects and figures depicted in the earliest Cubist paintings are often distorted and abstracted they are not difficult to recognize. In these paintings Picasso experimented with the representation of objects in space by emphasizing three-dimensional mass and form. The woman’s head in Woman with Pears is depicted using blocky geometric shapes.

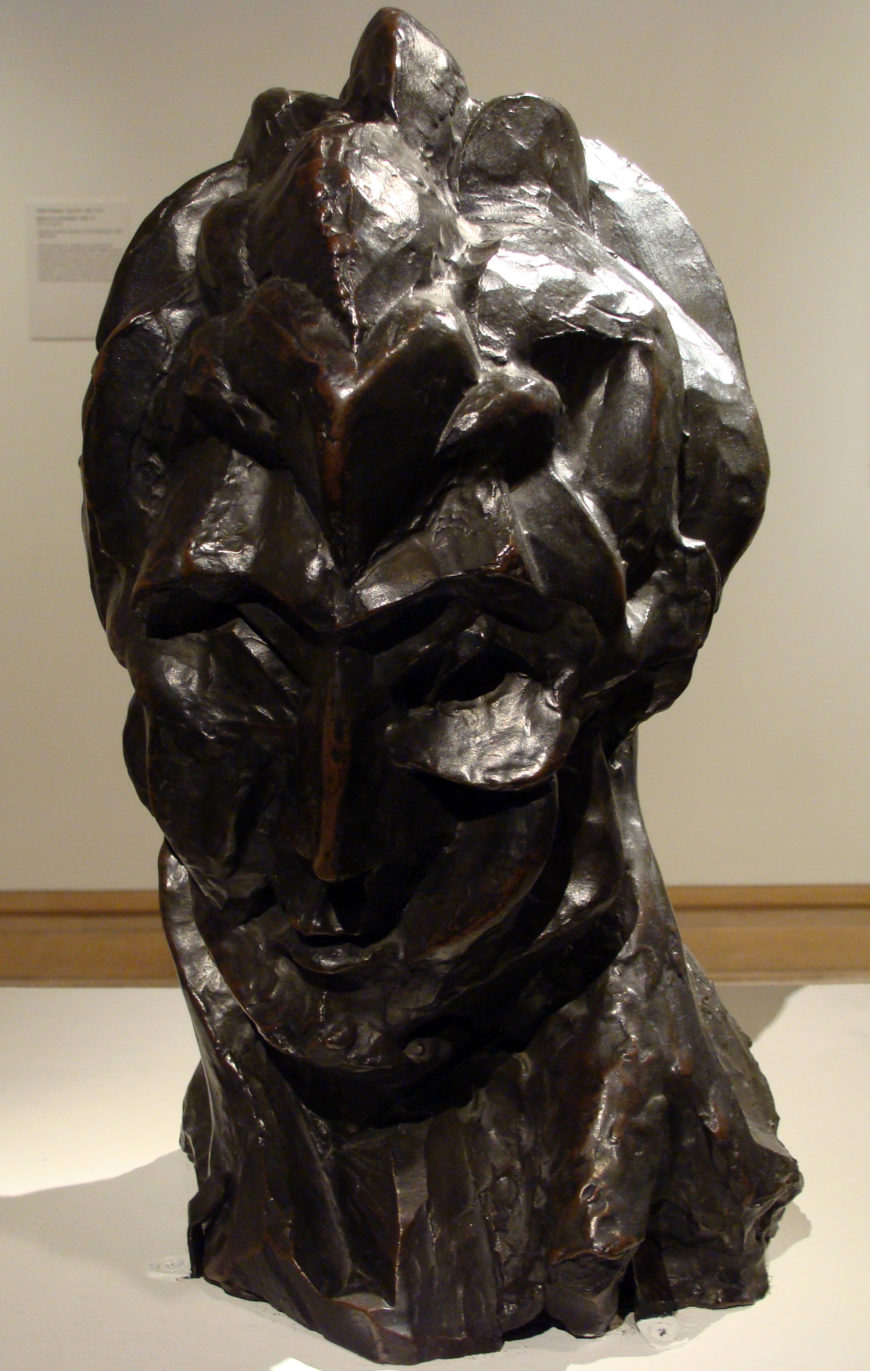

Picasso does not just simplify the surface planes of her head into basic geometric forms; he exaggerates shapes to invent a new abstracted structure. The forehead becomes a series of separate projecting and recessed cubic forms, while the tendons of the neck look like massive concrete supports buttressing the head. Picasso similarly abstracted the head into a complex of geometric shapes in the sculptures he made at this time as well.

Pablo Picasso, Woman’s Head (Fernande), 1909, bronze, 16 ¼ x 9 ¾ x 10 ½ inches, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (photo: Ben Sutherland, CC BY 2.0)

One thing that makes Woman with Pears easier to read than Kahnweiler’s portrait is Picasso’s use of contrasting colors to clearly separate figure from background. However, we can also see that the angular abstracted shapes in the background echo the forms of the woman’s head. This has the effect of creating a strong pattern on the surface of the canvas. Instead of receding into the background, the folds of the green curtain parallel the structure of the neck, and the scattering of fruit on the table imitates the shapes of the woman’s face. It is the complex ambiguity of representing three-dimensional objects in space on a painting’s two-dimensional surface that would become a central focus of Picasso’s (and his colleague Braque’s) Cubism.

Shattering form and space

In Portrait of Ambrose Vollard, painted a few months before the portrait of Kahnweiler, Picasso has shattered the figure into a collection of angular planes that extend into the surrounding space like pieces of a broken window. The head is easy to identify, largely because it is painted in naturalistic flesh tones and stands out next to the surrounding grays. Shadowed facets on the forehead and eyes are reminiscent of the woman’s boxy forehead in Woman with Pears, but unlike the figure in that painting, the rest of the body has no solidity and merges entirely with the background.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Ambrose Vollard, 1910, oil on canvas, 36 1/4 x 25 5/8 inches (Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow)

Rather than sculptural form, Picasso’s Portrait of Ambrose Vollard is largely composed of lines and floating abstract planes defined by apparently random chiaroscuro shading. Other than the face, nothing seems solid or certain. The vague outlines of a bottle in the upper left and the suggestion of architectural forms in the upper right are more legible than Vollard’s body in the foreground. We can just distinguish the suggestion of shoulders and arms in the shaded planes below the head. Perhaps the white planes in the center indicate the man’s shirt front.

Between Woman with Pears of 1909 and Portrait of Ambrose Vollard painted the following year, Picasso’s investigations into the abstract representation of three dimensional forms in space changed significantly. The same change is evident in Braque’s contemporary works. The two artists’ early analysis and abstraction of solid masses emphasized solidity at the expense of surrounding space. The later paintings emphasize the representation of space at the expense of solid three-dimensional forms.

A traditional portrait?

The portrait of Kahnweiler extends this breakdown of solid form even further. The simplification of complex three-dimensional forms to arrangements of angular facets that advance and recede into a flickering gridded arrangement of shadows and highlights creates a ghostly appearance. It is as if Kahnweiler and his surroundings are simultaneously materializing and dematerializing as we look at the painting.

Left: Pablo Picasso, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, oil on canvas, 39 9/16 x 26 9/16 inches (Art Institute of Chicago); Right: Diego Velazquez, Juan de Pareja, 1650, oil on canvas, 32 x 27 1/2 inches (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Unlike Vollard’s portrait, Kahnweiler’s face has no color to distinguish clearly it from the surrounding space. Suggestive areas of dark forms indicate the general shape of the figure. Although difficult to see, the figure dominates the center of the canvas as it does in Vollard’s portrait. This is the traditional format used in European half-length portraits like Diego Velazquez’s Juan de Pareja. Within this centralized dark area, lighter quadrilaterals and triangles on the upper portion suggest Kahnweiler’s face, neck, white shirt, and tie. At the bottom of the canvas another central area of lighter forms reveals his folded hands, and a few lines indicate the basic shapes of his fingers.

A few legible references

When we examine the upper portion of the figure we can see more details in the face. Simplified cubic forms describe the eyes and surrounding facial structure, while a shaded cylinder suggests the nose. A parallel set of linear curves arching above the face indicate the art dealer’s slicked back hair, and another curve under the nose suggests a mustache or simplified mouth.

Below the projecting angle of the chin there is a suggestion of a white collar, tie and pleated shirt front, and further down two light horizontal curves indicate Kahnweiler’s watch chain gleaming against his dark jacket. Picasso said he added these legible references to natural forms to the overwhelmingly abstract composition late in the painting process in order to help viewers recognize the subject.

Kahnweiler is not portrayed in an abstract empty space. There is a tabletop still life in the bottom left corner of the painting, with the upper portion of a long-necked bottle easily discernible. Suggestions of architectural elements and other objects appear as well.

Art historians have identified the shadowy forms of an African mask in the upper right and an Oceanic sculpture from New Caledonia in the upper left, both artifacts owned by Picasso. Non-western works from Africa and Oceania were key inspirations for Picasso’s initial abandonment of Western techniques of representation and his later development of the abstract approaches associated with Cubist sculpture and collage.

Picasso’s portrait of Kahnweiler presents the essential innovations of Analytic Cubism. Three-dimensional forms are simplified into geometric shapes and combined with nonrepresentational geometric planes to create ambiguous relationships between mass and space. The use of light and shade further emphasizes the spatial ambiguities and abstract pattern on the surface of the canvas. A visible mosaic of brushstrokes adds to the surface pattern and enhances the modernist tension between the painting’s representation of objects in space and the painting as a flat plane.