Marcel Janco, Portrait of Tristan Tzara, 1919, mixed media, 55 x 25 x 0.7 cm (Centre Pompidou, image: public domain)

This mask doubles as a portrait of the poet and Dada co-founder Tristan Tzara. Created in 1919 by the painter and architect Marcel Janco (also known in Romanian as “Iancu”), the mask-portrait is an important and rare document of the Dada movement and an embodiment of the so-called “approximate man” — a term that encapsulates many of the movement’s characteristics (“Approximate Man” is the title of a book-length poem by Tzara).

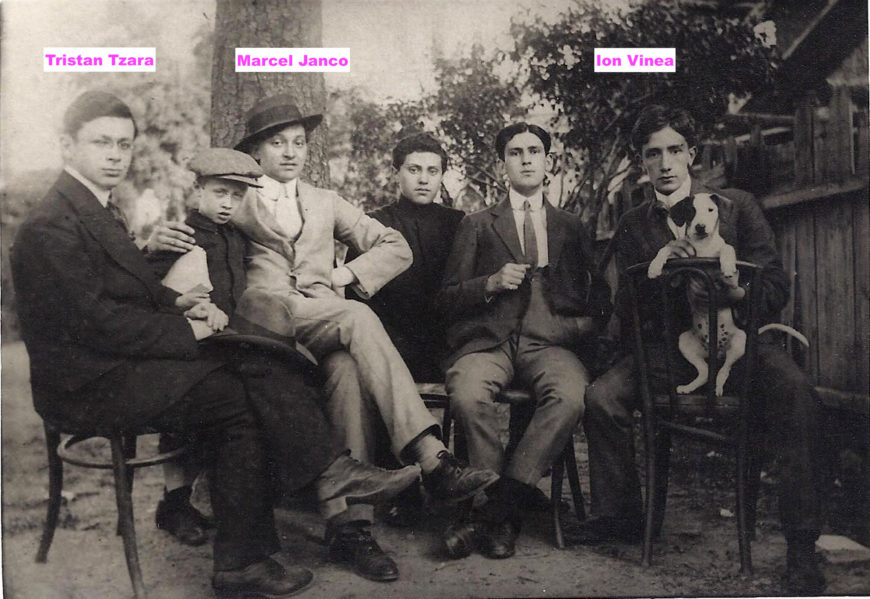

Tzara and Janco were both Jewish Romanian intellectuals at the epicenter of the European avant-garde during World War I; their artistic pursuits were instrumental in the emergence of the Dada movement in Zurich, at the now-famous Cabaret Voltaire.

The outbreak of World War I made many of Europe’s youth to flee to Zurich, in the neutral country of Switzerland, where they could pursue their studies, avoid being drafted, and even express their opposition vis-à-vis the absurdity of war.

Both Janco and Tzara were among these youth; Janco arrived in Zurich in 1914, Tzara in 1915. They both enrolled at the University, where they met again, since they had already established a friendship as high schoolers in Bucharest. There, in 1912, together with another friend, Ion Vinea, they established the literary magazine Simbolul (“The Symbol”), in whose pages Tzara had published his first Romanian-language poetry, illustrated with drawings by Janco.

Tristan Tzara is the poet’s pseudonym, which he fully adopted in 1915 in Zurich (he was born Samuel Rosenstock). “Tristan” is a reference to Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde, while “Tzara” is a variant of the Romanian word for “(home) country.”

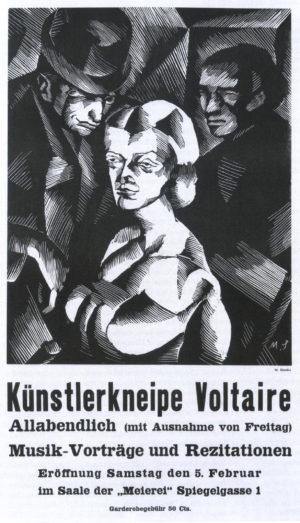

Poster for the opening of Cabaret Voltaire, 1916, lithograph by Marcel Slodki (Kunsthaus Zurich, image: public domain)

In Zurich, Janco and Tzara entered a closely-knit group of artists, all of whom are now remembered as the core members of Dada. Among these artists was the Alsatian sculptor and painter Hans/ Jean Arp, who fled to Zurich in 1915, simulating a mental illness in order to eschew being drafted for war. There he met the Swiss dancer and visual artist Sophie Taeuber, who would become his wife. In the same circles were the writer Hugo Ball and his partner, the poet and cabaret singer Emmy Hennings. Ball was discharged from war service on medical counts and had become a staunch pacifist. In a similar situation was Ball’s friend Richard Huelsenbeck, an antiwar writer who later became a psychiatrist in Long Island, NY.

It was Ball who founded, in 1916, the Cabaret Voltaire, named after the French Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire.

At this cabaret, these interconnected artists established Dada. The origin of this unusual name for the group remains controversial. Tzara claimed to have coined it; according to the most recounted narrative, Tzara would have found this word by chance in a Larousse dictionary he opened at a random page.

Marcel Janco, Portrait of Tristan Tzara, 1919, mixed media, 55 x 25 x 0.7 cm (Centre Pompidou, image: public domain)

The portrait of Tzara by Janco is one of several visual sources that help us understand what went on at the Cabaret Voltaire. In an era where video recordings were not yet possible, the only documentation we have of the creative output of the Dada group is in the form of literary sources like memoirs and diaries and some visual sources, namely paintings and photographs.

What these sources show us is that the Cabaret Voltaire became home to multimedia performances combining poetry, music, visual arts (notably collage and posters), and dance (often entailing the use of masks and puppets). These performances were modeled on the aesthetic principles of Richard Wagner and Wassily Kandinsky and echoed the notion of a “total work of art” (a work of art that makes use of many art forms, also called Gesamtkunstwerk).

Amid the resources for visualizing these Dada performances was a painting by Marcel Janco from 1916, titled Cabaret Voltaire. Although the painting no longer exists, we still have a grayscale photograph and a color lithograph of it.

The painting offered a bird’s eye view of the incendiary atmosphere of those Dadaist soirées. People in the audience, seated at tables, look like an electrified crowd: they laugh, chat, yell, and gesticulate.

One of them points to the word „DADA”, legible on a banner above the pianist. Of all the faces, only one appears to be unchanged: a skull-like mask, reminiscent of African art, likely authored by Janco.

Left to right: Grayscale photograph of oil on canvas painting by Marcel Janco, 1916, Cabert Voltaire; color lithograph of the same painting; annotated lithograph identifying portrayals of Dada artists within the painting and, in yellow, a man pointing to the word “Dada” and a mask, probably by Janco (images: Eduard Andrei)

Marcel Janco’s masks, costumes, and stage props were the artist’s most significant contribution to Dada performances. The simple materials he employed for their creation, such as burlap, paper, and rope, suggest that his masks and props were meant to be ephemeral, like the shows for which they were made, all conceived as one-time events. For this reason, some art historians think that the few Janco masks that are still extant are, in fact, later copies.

One of three masks attributed to Janco in the collection of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the mask known as the Portrait of Tristan Tzara is eerily oversized and stitched together of diverse materials (cardboard, jute canvas, string, ink, and gouache). As it has been noted, by Dadaist Hugo Ball and many others, art works like Janco’s mask redefined art making, relinquishing traditional drawing and paintings methods for unexpected juxtapositions of materials achieved by means of collages and montage.

In Portrait of Tristan Tzara, the unusual size and the childlike combination of heterogenous textures demonstrate Janco’s playful approach to his art. He does not stifle or control the accidental creases of the cardboard or the unraveling of the canvas bits, but uses them to increase the expressive force of the ensemble. For example, the casual drop of the string is utilized to call to mind the strap of Tzara’s monocle. This is not the only such use of string in Janco’s work; in another mask (shown here to the right), the string is used to stand in for the moustache of the figure.

Chance and spontaneity are key concepts for Dada artists. Janco’s Portrait of Tristan Tzara presents yet another key Dada element, namely asymmetry. For example, while one eye is round and seemingly enlarged due to the monocle that cover it, the other eye is merely suggested by the angled line that stands in for the eyebrow.

Anthropomorphic mask, early 20th century, Ivory Coast, formerly owned by Tristan Tzara (Musée du Quai Branly)

The elongation of the face, like an inverted triangle, demonstrates the influence of African masks. A mask that once belonged to the private collection of Tristan Tzara is now housed in the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. The Portrait of Tristan Tzara epitomizes the Dada artists’ interest in African art — an interest shared by both Tzara and Janco. However, Janco’s masks were not direct quotations of specific African or Oceanic masks. Instead, his masks were original creations that drew on the formal characteristics of African masks, translating some of their visual identity by means of strikingly different, ephemeral materials.

This source of inspiration for Dada needs to be understood in the context of the highly problematic “primitivism” and “exoticism” of the early 20th century, fueled by colonialism.

Romanian folk mask (The National Museum of the Romanian Peasant, Bucharest)

At a strictly formal level, European artists’ encounter with the plastic vocabulary of African art — though devoid of any understanding of that art’s context and meaning — contributed to revolutionizing European artistic expression.

According to the Dada-Afrika exhibition of 2016, organized on the occasion of the Dada centennial by the Rietberg Museum in Zürich, the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, and the Berlinische Galerie, there may be other influences in Janco’s masks, for example, the Swiss carnival masks from the Lötschental region.

Another source of inspiration, as shown by some scholars, could have been the folk masks worn by carolers in Romanian villages.

These different sources have in common a quest for a return to an archaic, mythical time, construed differently by different cultures across Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Sophie Taeuber dancing with a mask by Janco, 1916-7, photographer unknown (image: Stiftung Hans Arp und Sophie Taeuber-Arp)

In a rare period photograph of Dada artist Sophie Taeuber, we see her wearing one of Janco’s masks while dancing. Unlike the Portrait of Tristan Tzara, this mask is three-dimensional, cubic, and fully enveloping the dancer’s head. However, this mask is similar to the Portrait of Tristan Tzara in that it, too, bears the influence of African art and achieves its expressive potential by means of a playful, geometric composition.

Whether three-dimensional like this mask or flatter like the Portrait of Tristan Tzara, Janco’s masks reveal the artist’s interest in space. On a side note, Janco’s investment in the spatiality of his art will gain full force in his later activity as an architect upon his return to Romania.

The use of such masks in performance affected the performer wearing the mask, dictating an attitude verging on pathos, if not madness. As Hugo Ball wrote in a note from May 24, 1916, on his first performance with a mask by Janco, the masks as props called to mind aspects of Japanese and ancient Greek theatre, while being squarely rooted in modern times.

“Janco has made a number of masks (…) They are reminiscent of the Japanese or ancient Greek theater, yet they are wholly modern. (…) Their varied individuality inspired us to invent dances, and for each of them I composed a short piece of music on the spot. (…) What fascinates us all about the masks is that they represent (…) characters and passions that are larger than life. The paralyzing horror of our time was thus made visible.”Hugo Ball, 1916, included in Die Flucht aus der Zeit, 1927

During World War I, the raw finish of Janco’s masks and the use of red paint might have been intended to evoke the blood, disfigurement, and widespread use of gas masks in war, which the Dada artists were against. After the war, in 1919, the Dada group experienced a series of internal problems leading to the (unofficial) dissolution of the group. The Dadaist notions of art and life give way to new ideas, notably the desire for a universal abstract art that can play an active, positive role in society.

From their first appearance at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 to the final soirée at the Saal zur Kaufleuten in 1919, Janco’s masks constituted an essential component of the Dadaist aesthetic. Complicated by their affinity and partial reliance on primitivist and exoticizing ideas of the time, Janco’s masks embodied an artistic credo of the Dada group. In Janco’s words, his masks expressed “our belief in a direct, magical, organic and creative art.” Notably, the Portrait of Tristan Tzara epitomized the notion of an “approximate man.” Tzara himself chose this phrase as the title of a poetry book of his from 1931 since it so aptly encapsulated Dada.