Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Gates, 1979–2005 (view across the pond looking southeast) (photo: Wolfgang Volz) © 2005 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

Nearly thirty years after the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude first conceived of The Gates, this logistically complex project was finally realized over a period of two weeks in New York’s Central Park. Each gate, a rectilinear three-sided rigid vinyl frame resting on two steel footings, supported saffron-colored fabric panels that hung loosely from the top. The gates themselves matched the brilliant color of the fabric. The statistics are impressive: 7,503 gates ran over 23 miles of walkways; each gate was 16 feet high, with widths varying according to the paths’ width. Despite a brief exhibition period—February 12th through 27th 2005—The Gates remains a complex testament to two controversial topics in contemporary art: how to create meaningful public art and how art responds to and impacts our relationship with the built environment.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands, Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida, 1980–83 (photo: Wolfgang Volz) © 1983. Estate of Christo V. Javacheff

Wrapped, surrounded, suspended

Since the 1960s, Christo and Jeanne-Claude have introduced eye-catching color into the landscape, for example pink in Surrounded Islands, 1980–83 in Biscayne Bay, Florida.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Valley Curtain, Rifle, Colorado, 1970–72 (photo: Wolfgang Volz) © 1972 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

The saffron color in The Gates was used to create “a golden ceiling creating warm shadows” for the visitor walking along the Central Park path. [1] The same color also appeared in an earlier work by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Valley Curtain, in Rifle, Colorado.

In contrast to many of their works that directly intervene in urban structures like the Pont Neuf in Paris or the German Parliament building in Berlin, where architectural masses are literally wrapped, Surrounded Islands and Valley Curtain engage, rather than seek to contain nature: a pink border of fabric floating around islands or a curtain suspended across a remote valley.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Gates, 1979–2005 (photo: Wolfgang Volz) © 2005 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

A public art

The Gates respond to spaces designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux within the dense urban grid of Manhattan. The artists complicate an environment that was, in fact, entirely invented in the mid-19th century to express the Victorian ideal of the pastoral and picturesque landscape.

This intrusion into Manhattan’s “natural environment” left many visitors uneasy, as in the case of Joanne Landy:

Whoever…wrote about the way the exhibit draws aesthetic attention to the park itself is off the mark, in my experience anyway. The flags just draw attention to themselves, period, and there appears to be no particular relationship to the shapes and colors of the park. That’s part of the problem. [2]

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Gates, 1979–2005 (photo: Wolfgang Volz) © 2005 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

Storm King Art Center (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A point of contrast can be seen at the Storm King Art Center, a renowned sculpture park 52 miles north of New York City that has successfully cultivated a dialogue between sculptures and their landscape for over fifty years. Whereas sculptures are installed within the meadows and rolling hills of Storm King’s grounds, The Gates were tied to the paths that meander through the park. This was done for two reasons: to avoid drilling thousands of holes into the soil and potentially harming the root systems of adjacent trees, and because Christo and Jeanne-Claude were inspired by the way the city’s pedestrians navigate its paths. Thus, in contrast to the works in Biscayne Bay and Rifle that divide and isolate forms in the landscape, The Gates aligned itself along pre-existing pathways of movement.

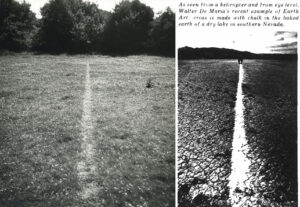

Left: Richard Long, A Line Made by Walking England, 1967 © Richard Long; right: Walter De Maria, One Mile Long Drawing, 1968, Mohave Desert © Estate of Walter De Maria

Pathways

A path cut into a pristine natural environment is very much an intervention, as evidenced in Richard Long’s A Line Made by Walking, 1967 and Walter De Maria’s One Mile Long Drawing, 1969.

However Central Park, a much-loved urban oasis, is one of the most famous examples of urban planning. The Gates reinforce and highlight pre-existing routes within this manmade environment. Critiques of The Gates that are rooted in the issue of the artwork’s relationship with nature are therefore curious since the Park itself is not an untouched natural space.

This installation alters the experience of seeing and walking along the paths that run throughout the park. The title alludes to a threshold, a point of exit and entrance. In fact, in some places, the structures form an oval. There is no starting point and no end point and moreover, no favored point from which to view the work. It is an installation made for the pedestrian in motion and not a static object that asks us to stand still before it.

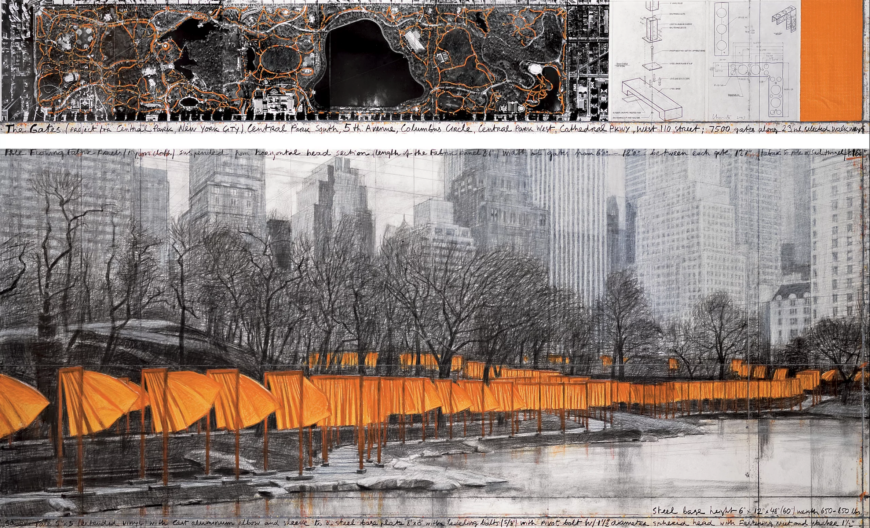

Christo, The Gates (Project for Central Park, New York City), 2003, 38 x 244 cm and 106.6 x 244 cm, pencil, charcoal, pastel, wax crayon, fabric sample, aerial photograph, and hand-drawn technical data (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; photo: André Grossmann) © 2003 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

Bureaucratic collaborators

The Gates cost 21 million dollars and both the artists and the supporting institutions (the City of New York and the Central Park Conservancy) were quick to emphasize that Christo and Jeanne-Claude financed the project themselves and that the installation was free to the public. The artists sold preparatory drawings related to The Gates, and other works, before the exhibition opened; they rely on this method to independently fund their projects since they do not accept sponsors. Though the City and the Central Park Conservancy did not use public money to support this project, their approval and support were seen as an invaluable currency by many critics. Months before The Gates debuted, both institutions had worked in concert to prevent United for Peace from holding an antiwar demonstration in Central Park to coincide with the Republican National Convention which was held in New York that year.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Reichstag, 1971–95 (photo: Gertrud K., CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) © Christo

It is important to remember that Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s favorable turn with the powers that be was 26 years in the making. The artists submitted proposals, attended meetings, and made presentations throughout this period, persisting even after they received a 251-page official rejection only three years into their campaign. Many consider the 2001 mayoral election of Michael Bloomberg—a Christo and Jeanne-Claude collector—as the turning point in this saga. The artists are accustomed to bureaucratic battles, an inevitability given subjects that reshape iconic structures such as their The Pont Neuf, Wrapped, 1975–85, Wrapped Reichstag, 1971–95, and The Gates.

Art designed to end

It might seem odd that Christo and Jeanne-Claude invest so much time, effort, reputation, and money in creating ephemeral non-collectible artwork. Yet they are completely devoted to this kind of artistic practice:

The temporary quality of the projects is an aesthetic decision. Our works are temporary in order to endow the works of art with a feeling of urgency to be seen, and the love and tenderness brought by the fact that they will not last. Those feelings are usually reserved for other temporary things such as childhood and our own life. These are valued because we know that they will not last. We want to offer this feeling of love and tenderness to our works, as an added value (dimension) and as an additional aesthetic quality. [3]

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Gates, 1979–2005 (photo: Wolfgang Volz) © 2005 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Foundation

In the end the show took about six weeks to install and The Gates came down the day after the exhibition ended, with most of the materials headed for recycling. The artists maintain a thorough archive of their work on their website; along with projects that never materialized (including several for New York City) and current projects (not surprisingly these are decades in the making). With Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s passing in 2009 and 2020 respectively, of the past, present, and future is poignant in its meticulous documentation and optimism—evidence of the duo’s perseverance and monumental dreams.

Notes:

[1] Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Gates.

[2] Jesse Lemish, “Art for the People? Christo and Jean-Claude’s ‘The Gates,’” New Politics, volume 10, number 3 (Summer 2005).

[3] Christo and Jeanne-Claude in Their Own Words, NYC.gov, 2005.

Additional resources