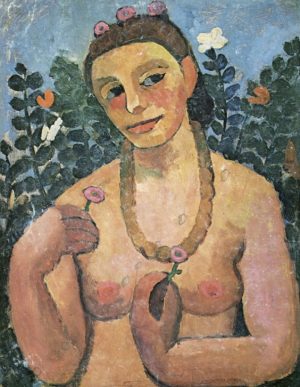

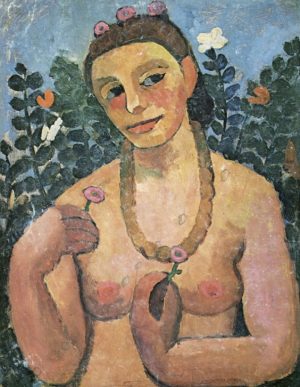

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait Nude with Amber Necklace, 1906, oil on cardboard, 62.2 x 48.2 cm (Museen Böttcherstraße, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen)

A first in art history

We don’t usually hear of relationship dramas in art history, but on the night of February 23, 1906, the German artist Paula Modersohn-Becker secretly left her husband and stepdaughter in the German town of Worpswede and boarded a train for Paris. As she wrote the next day in her journal, “I left Otto Modersohn and I’m poised between my old life and my new life. I wonder what the new life will be like… Whatever must be will be.”

During Modersohn-Becker’s time in Paris between 1906 and 1907 she almost single-handedly invented a new genre in European modern art: the nude, female self-portrait. In doing so Modersohn-Becker depicted female self-understanding in a way never quite seen before in the history of modern art—precisely at a time when European women were increasingly demanding their social and political independence.

Self-Portrait Nude with Amber Necklace, Half-Length I is one of two similar paintings Modersohn-Becker produced in the hot Paris days of August 1906. In the work, the artist depicts herself nude in a natural, botanical setting. Wreathed in her signature necklace (a motif that appeared often in this period), she decorates herself in pink flowers. Three flowers dot the top of her head, while she gently carries two more in each hand. Behind her, a verdant mass of green leaves and stems sprawls upwards; two white flowers appear on either side of her as butterflies flit about and encircle her. Most striking in the painting is, naturally, Modersohn-Becker’s nude figure, with her breasts occupying the lower center of the image as they rhyme with the swoop of the necklace. The artist seems utterly at ease in her lack of dress; her posture is casual, even happenstance. She glances upwards with a sly smile.

Though “Self-Portrait Nude” conveys a sense of calm and contentment, the painting should be understood as a near-revolutionary act in the history of modernism. The female nude had long been a staple in the repertoires of male painters, from Italian Renaissance artists (like Titian) to key figures in nineteenth-century French painting (such as Édouard Manet). Around the beginning of the twentieth century in particular, modernists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse (artists whom Modersohn-Becker studied closely) revamped the female nude for the sake of artistic experimentation, whether they wanted to investigate the possibilities of abstraction or explore themes of free sexuality and uninhibited morality.

As feminist art historians began arguing in the 1970s, these works by artists like Picasso and Matisse seemed to objectify the female body. Their sitters were made sexually available, even defenseless; they were designed for a male viewer and his desire. The question is then, if a woman artist depicted herself in the nude, could this be an act of agency or self-assertion? How could female artists position their work within the ground-breaking aesthetics of modernism while expressing their own gendered experience?

Detail, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Girl blowing a flute in birch forest, 1905 (Museen Böttcherstraße, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen)

Being an artist and a woman

For all of her career, Modersohn-Becker, born Paula Becker, struggled to find her footing as a professional artist. She only sold two works during her lifetime and after disastrous reviews of an early exhibition in 1899, she shied away from showing her work publicly. Few women artists in Europe achieved any real celebrity and a sustainable career typically required independent wealth. Moreover, a woman artist’s educational opportunities were far more restricted than those of their male counterparts. While drawing from live, nude models was considered the standard for a proper (male) artist’s training, women had difficulty accessing these lessons due to moral codes and gender-segregated schooling. Modersohn-Becker could only first practice so-called “life drawing” at age 20 at an art school in Berlin intended for female students. However, different educational opportunities began cropping up in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century—for both men and women.

Worpswede

In 1899, Modersohn-Becker joined the artists working at the so-called Worpswede Artist Colony in a small, moorland town north of the German city of Bremen. (Male) artists, including Fritz Mackensen, Hans am Ende, and Otto Modersohn established the colony, drawing influence from the rustic landscape and experimenting with styles and approaches not taught in the formal art academies.

In 1899, Modersohn-Becker joined the artists working at the so-called Worpswede Artist Colony in a small, moorland town north of the German city of Bremen. (Male) artists, including Fritz Mackensen, Hans am Ende, and Otto Modersohn established the colony, drawing influence from the rustic landscape and experimenting with styles and approaches not taught in the formal art academies.

At Worspwede, Modersohn-Becker worked with these figures, including the poet Rainer Maria Rilke and the sculptor Clara Westoff, eventually marrying Otto Modersohn in 1901 and adding his last name to her own.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Child on red cube pillow, c. 1904, 66,2 cm x 58 cm (Museen Böttcherstraße, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen)

In the Worpswede environment, Modersohn-Becker began practicing the format that would come to dominate her career, portraits of women and girls, especially mothers and their children. This latter theme was not new in the history of art (think of all the Madonna and Child paintings from the medieval period onwards), but Modersohn-Becker avoided the typical approaches that male artists adopted; instead of focusing on the idealized virtues of the family-unit, she depicted maternity, childhood, and femininity as elemental, psychologically charged experiences. In Child on Red Cube Pillow, for example, a toddler sits somberly on a pillow that seems to be elevating in ambiguous perspective. Despite the child’s age and her somewhat elaborate dress, the sitter carries an intense, introspective quality.

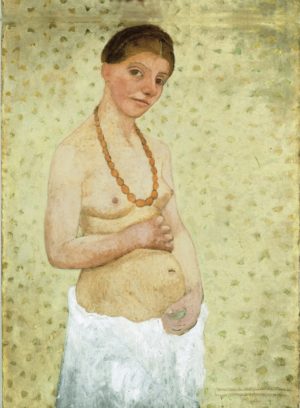

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-portrait on the 6th wedding anniversary, oil and tempera on cardboard, 1906 (Museen Böttcherstraße, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen)

While in Worspwede, Modersohn-Becker was already traveling to Paris frequently to develop her work. In 1900, she took life classes at the Colarossi Academy, attended anatomy lectures open to the public at the School of Fine Arts, and sketched works on display at the Louvre Museum. By the time she visited again in the late winter of 1905, she had absorbed the influences of artists like Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, and Vincent van Gogh. Despite Worpswede’s experimental ethos, for Modersohn-Becker, Paris offered an ideal context in which to work and live alone outside a disappointing marriage (Paula and Otto would not consummate their marriage for five years).

Once in France, Modersohn-Becker struggled to make a living but was nonetheless prolific. In May 1906, she painted Self-Portrait on Her Sixth Wedding Anniversary, 25th of May, considered to be the first nude female self-portrait created in modern art (and with the artist imagining herself pregnant, to boot.) However, with Otto’s frequent attempts to save their marriage and her own financial difficulties, Modersohn-Becker eventually reconciled with her husband and in March 1907, moved back to Worpswede with the caveat that she’d return to Paris each winter. In November of that year, at age 30, she died of an embolism, three weeks after giving birth to her only daughter, Mathilde.

Self-Portrait Nude with Amber Necklace

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait Nude with Amber Necklace, 1906, oil on cardboard, 62.2 x 48.2 cm (Museen Böttcherstraße, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen)

Seen in light of her biography, Modersohn-Becker’s Self-Portrait Nude represents the artist’s claim to her own self-depiction, even if her immediate life circumstances prevented a sustainable sense of autonomy. In the painting, the artist luxuriates in her body and her gender; she presents herself as part of nature, set as she is against the green leaves, but she also insists on adornment. While there is a sensuality to the image, it’s not a sexuality per se that requires male validation or even acknowledgement. Scholars believe that Modersohn-Becker in fact painted Self-Potrait Nude in front of a mirror in her studio; the painting is a dialogue between the artist and how she understands herself at a particular moment. This work is not just about a timeless, eternal sense of femininity or a totally fixed sense of self.

At the formal level, Modersohn-Becker distinguishes each brushstroke and gesture through relatively discrete sections of skin tone and color; the very making of the painting is visible. Moreover, the butterflies in the background certainly represent the natural world, but they also signify change: just as larvae metamorphose into cocoon states and then butterflies, so too can the artist constantly transform through their practice. As Modersohn-Becker wrote in an early letter to the poet Rilke, “What is finished? And when is one finished? Hopefully never.”