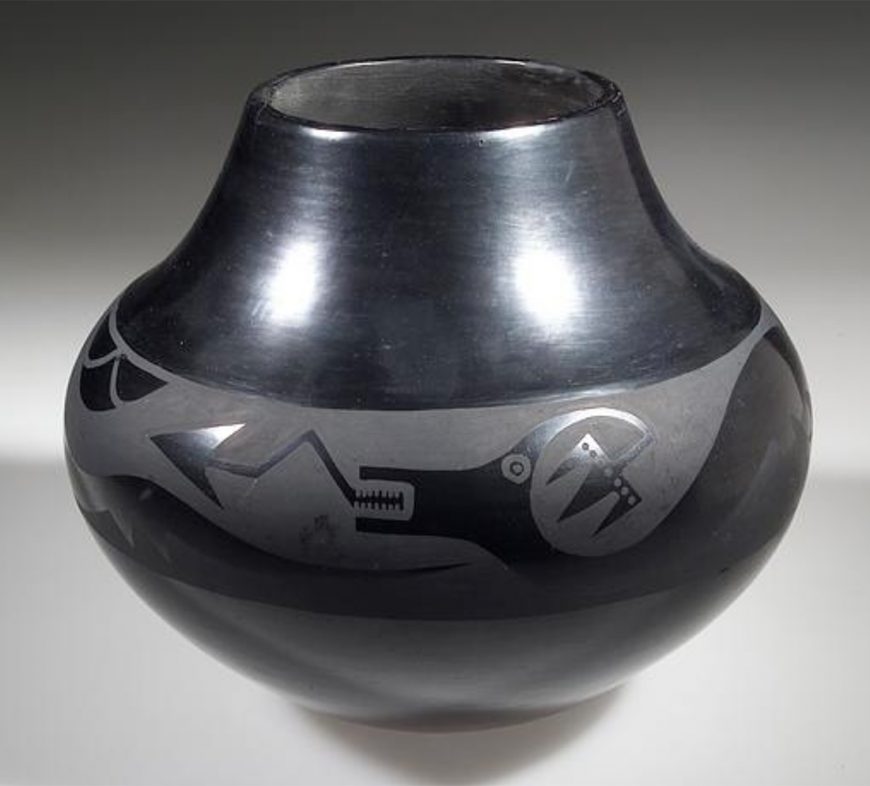

Maria and Julian Martínez, pot with avanyu design, 1934-43, 21.7 x 26.7 cm (National Museum of the American Indian)

Famous Pueblo pottery

As an artist, Julian Martínez from San Ildefonso Pueblo is best known for the ceramics he made with his wife, Maria Martínez. Together, they produced the matte-black on polished-black pottery for which they and their Pueblo colleagues gained international fame.

Maria formed the pots into elegant shapes and Julian painted the designs, both geometric and figurative, including historic motifs such as the feather pattern from Mimbres pottery and the avanyu, the horned serpent similar the Mesoamerican deity Quetzalcoatl.

Julian Martínez also worked at the Museum of New Mexico, where he took advantage of the opportunity to study the Museum’s collection of Southwestern pottery, and he learned more during the summers when he worked at the field school at the Pajarito Plateau (later renamed Bandelier National Monument). In addition to his work on pottery, Martínez drew on paper; he always kept a notebook where he sketched ideas and recorded what he had seen. Though most of his images were painted on paper, he created a few murals on walls and, on rare occasions, he painted on hide, as he did for his Buffalo Dancers from about 1930, now in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City (below).

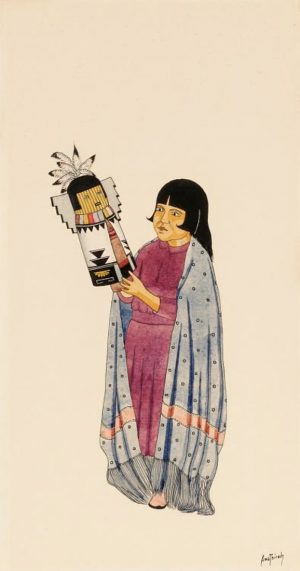

Awa Tsireh (Alfonso Roybal), Girl Holding Kachina, c. 1920-30, watercolor and pencil on paper (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Pueblo painting

Painting has long been part of Pueblo life; it can be found on the walls of the kivas (the round ceremonial structures usually partially underground) and on dance regalia such as wands, tablitas (ceremonial headdresses), clothing, and other items. A thriving art community developed around 1900 during a difficult time in Pueblo history: due to illness and outward migration, the population was reduced to less than 200. When the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railway extended its track to the area in 1880, the economy of the Pueblo was transformed as more outside goods were purchased and more items, especially ceramics and paintings on paper, were made to sell to tourists traveling to the area.

An important group of Pueblo artists called the San Ildefonso Self-Taught Group, active from around 1900 to around 1930, included Julian Martínez, Tonita Peña, Crescencio Martínez, and Awa Tsireh (Alfonso Roybal). Most of their work depicted scenes common to Pueblo life, mainly ceremonial dances and genre scenes.

The Buffalo Dance

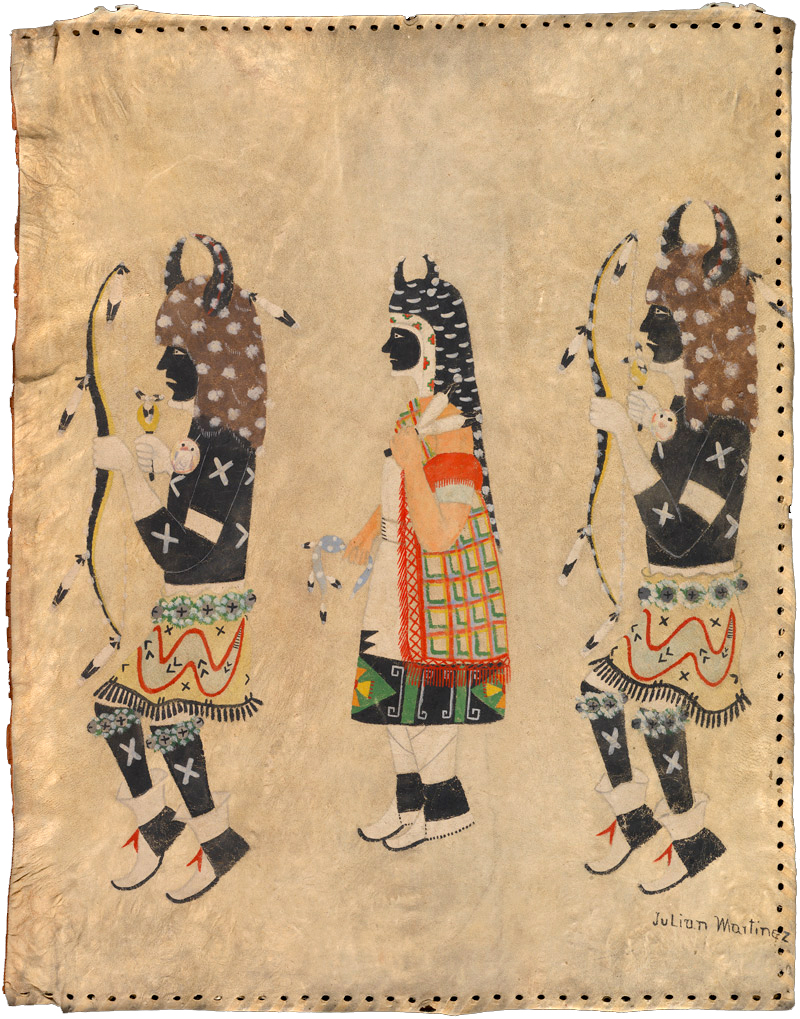

Martínez was elected governor of San Ildefonso in 1925 and he served as a leader in ceremonies. Like other Pueblo painters, he refrained from depicting ritual objects, sites, and altars that were considered private, and focused instead on dances that were open to the public. The Buffalo Dance is one of the most commonly represented of all Pueblo dances by the Self-Taught Group. Art historian J.J. Brody described it as one of the most “comprehensible to outsiders of all public ritual dances of the Pueblo people.” [1] Performed annually on January 23rd to honor the Pueblo patron saint, San Ildefonso, the Buffalo Dance enacts a hunting scene, with three dancers playing the roles of a hunter, buffalo, and a buffalo maiden (or buffalo mother) who has the power to induce the animals to sacrifice themselves to provide food and hide.

Early twentieth-century Pueblo paintings by artists including Tsireh, Peña, and Martínez all depict the Buffalo Dance in the same way, with the three figures in profile, facing the same direction as they would be during the dance. The men wear a buffalo headdress and dance kilts with depictions of avanyu (a horned serpent), and their skin is painted black. The buffalo maiden wears an embroidered one-shouldered manta, or dress.

Julian Martínez, Buffalo Dancers, c. 1930s, hide and paint, 79 x 61 cm (National Museum of the American Indian)

In this hide painting, Martínez gave all three figures the same facial features, focusing instead on varying details in their clothing and regalia. There is no sense of space; the figures lack modeling and do not cast shadows. The flatness of the figures and the lack of a background suggest the influence of early Modernist abstraction. The empty space might also symbolize an area that is sacred—unbound by place or time. Paintings of such dances might even portray a space where the viewers themselves also participate in the dance, because, as anthropologist Alfonso Ortiz from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo has observed, everyone in the community dances in ceremonies.[2]

Though Martínez painted several versions of the Buffalo Dance, the NMAI version is unusual for its material: animal hide. More commonly used in art from the Plains, hide is stronger and suppler than paper as a base. This particular hide has small holes on three of its sides, suggesting that it was used to cover a portfolio or large book, with a string or leather cord run through the holes to attach it over a group of drawings.[3] Later, the image may have been unlaced and cut along one side, accounting for the smooth edge.

Pueblo painting continues

With its bright colors and strong forms, Julian Martínez’s Buffalo Dancers exemplifies the early period of Pueblo painting. In 1932, the Santa Fe Indian School (whose painting program became known as “The Studio School”) started teaching art, and developed the Santa Fe Indian School Style. This new style retained the earlier emphasis on dance and genre scenes with the same flatness and lack of modeling, but the work became more decorative and lost the intimacy of the earlier works.

During Martínez’s life, local artists, anthropologists, and ethnographers expressed their appreciation for his work, noting his radiant colors, technical skill, and mastery of form. Martínez’s Buffalo Dancers, like other paintings produced by the San Ildefonso Self-Taught Group, conveys a sense of movement and energy in its figures and shares the joy of the ceremonies.

[1] J.J. Brody, Pueblo Indian Painting: Tradition and Modernism in New Mexico (School for Advanced Research Press, 1997).

[2] Alfonzo Ortiz, The Tewa World: Space, Time, Being and Becoming in a Pueblo Society (Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1969).

[3] I am indebted to Dr. Jonathon Batkin and Dr. Bruce Bernstein for sharing this idea.

Additional resources:

This work in the Infinity of Nations exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian

Claremont Colleges Digital Library, “Pueblo and Plains Indian Watercolors.”

Mimbres Pottery (from the Smithsonian)

Anthes, Bill. Native Moderns: American Indian Painting, 1940–1960. (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2006).

Bruce Bernstein, and Jackson Rushing. Modern by Tradition: American Indian Painting in the Studio Style. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1995).

J.J. Brody, Pueblo Indian Painting: Tradition and Modernism in New Mexico, 1900-1930. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of Advanced Research Press, 1997).

—. Anasazi and Pueblo Painting. (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1991).

—. Indian Painters and White Patrons. (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1971).

Ruth Bunzel, The Pueblo Potter: A Study of Creative Imagination in Primitive Art. (1911) (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1972).

Ina Sizer Cassidy, Art and Artists of New Mexico. (Bureau of Publications, State of New Mexico, 1943).

Katherin L Chase, Indian Painters of the Southwest: The Deep Remembering. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of Advanced Research, 2002).

Dorothy Dunn, .American Indian Painting of the Southwest and Plains Area. (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1968).

—. “The Studio: 1932-1937: Fostering Indian Art as Art,” El Palacio vol. 83, no. 4, pp. 5-9.

Aaron Fry, “Local Knowledge and Art Historical Methodology: A New Perspective on Awa Tsireh and the San Ildefonso Easel Painting Movement,” Hemispheres: Visual Cultures of the Americas 1 (Spring, 2008): pp. 46-61.

Jessica Horton and Janet Catherine Berlo, “Pueblo Painting in 1932: Folding Narratives of Native Art into American Art History,” in John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill, and Jason D. LaFountain, editors, A Companion to American Art. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015).

Alice Marriott, Maria: The Potter of San Ildefonso (1948) (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987).

Elizabeth A Newsome, “Reflexivity and Subjectivity in Early Native American Painting: A Critique of Perspectives on the Traditional Style,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 25:3 (2001), pp.103-142.

Alfonzo Ortiz, The Tewa World: Space, Time, Being and Becoming in a Pueblo Society (Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1969).

—, “Dual Organization as an Operational Concept in the Pueblo Southwest,” Ethnology, vol. 4, No. 4. (October 1965), pp. 389-396.

David W Penney. and Lisa Roberts. “America’s Pueblo Artists: Encounters on the Borderlands,” in W. Jackson Rushing III, editor, Native American Art in the Twentieth Century. (London: Routledge Press, 1999).

Susan Peterson, Living Tradition of Maria Martinez. First published in 1977. (Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International, 1989).

—. Pottery by American Indian Women: The Legacy of Generations. (New York, New York: Abbeville Press, 1997).

Rushing, W. Jackson, and Allan Houser. Allan Houser: An American Master (Chiricahua Apache, 1914-1994). (New York, New York: H.N. Abrams, 2004).

W. Jackson, Rushing, Native American Art in the Twentieth Century. (London: Routledge Press, 1999).

Sasha T. Scott, A Strange Mixture: The Art and Politics of Painting Pueblo Indians. (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015).

Tryntje Van Ness Seymour, When the Rainbow Touches Down: The Artists and Stories Behind the Apache, Navajo, Rio Grande Pueblo, and Hopi Paintings in the William and Leslie Van Ness Denman Collection. (Phoenix, Arizona: Heard Museum, 1988).

Julie Solometo, “The Context and Process of Pueblo Mural Painting in the Historic Era,” Kiva vol. 76, no. 1 (2010), pp. 83-116.

Richard Spivey The Legacy of Maria Poveka Martinez. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2003).

R. Strickland, “Where Have All the Blue Deer Gone? Depth and Diversity in Post War Indian Painting,” American Indian Art Magazine v. 10 (Spring 1985), pp. 36-45

Jill Drayson Sweet, Dances of the Tewa Pueblo Indians: Expressions of new life. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: School for Advanced Research on the, 2004).

Clara Lee Tanner, Southwest Indian Painting: A Changing Art. (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1971).

Sharyn Rohlfsen Udall, Contested Terrain: Myth and Meanings in Southwest Art. (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1996).

Edwin L. Wade, “Straddling the Cultural Fence: The Conflict for Ethnic Artists within Pueblo Societies,” in The Arts of the North American Indian: Native Traditions in Evolution, ed. Edwin L. Wade (New York, New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1986), pp. 243-254.