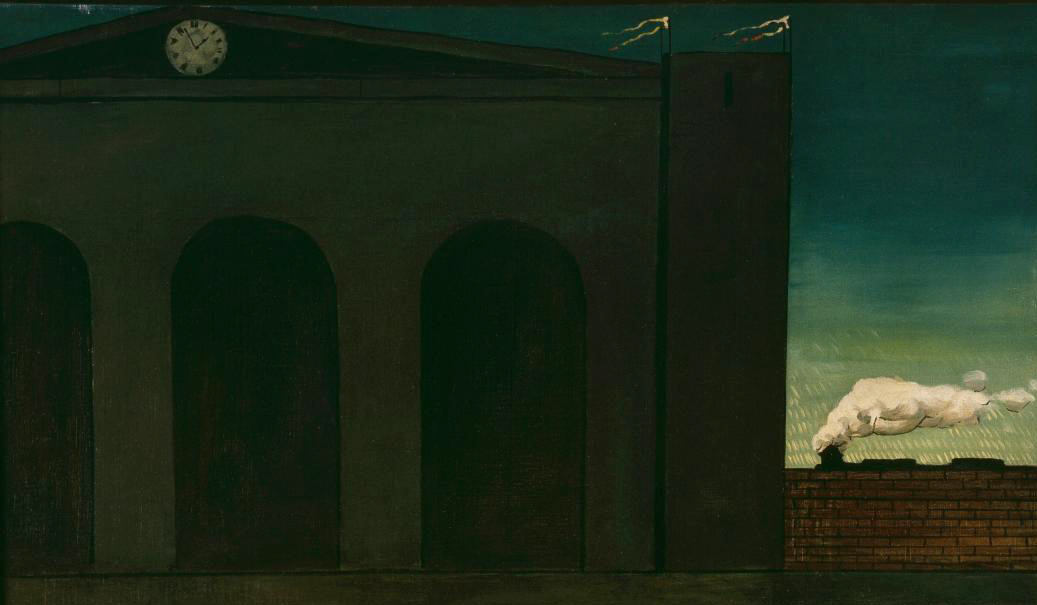

Giorgio de Chirico, The Soothsayer’s Recompense, 1913, oil on canvas, 135.6 × 180 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Giorgio de Chirico’s painting The Soothsayer’s Recompense presents a desolate piazza (city square) occupied by only a statue. In the background a train, barely visible behind a brick wall, arrives at a station. An arch frames several palm trees rising from behind the same wall. An evening sky renders the scene full of long shadows, sharp contrasts between light and dark, and sickly colors. The large-scale painting presents a subtly disquieting space that sparks many questions. Why does a statue of a woman languish in the empty space? What is the meaning of this puzzling work?

Although The Soothsayer’s Recompense remains open to interpretation, the painting contains elements that allude to the artist’s life, to popular myth, and to his interpretation of the philosophy of metaphysics. The Soothsayer’s Recompense was painted in 1913, during the artist’s famed Metaphysical period (1910–19).

Sleeping Ariadne, Roman copy after a Pergamon school original, early 2nd century B.C.E., Phrygian marble (Vatican Museums) (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Sleeping Ariadne, 2nd century C.E., marble, 2.26 x 1.29 x 1.03 m with significant 16th century restorations (Uffizi, Florence)

Classical mythology and personal symbolism

The classical statue languishing in the piazza is a painted representation of the mythological figure of Ariadne. More specifically, de Chirico’s rendering is based on his own viewing of multiple Roman copies of a Hellenistic Greek sculpture known as the Sleeping Ariadne statue. De Chirico combines different elements from versions of the sculpture that he saw at the Vatican Museums in Rome, the Uffizi Galleries in Florence, and the Louvre Museum in Paris. One of the most renowned sculptures of antiquity, Sleeping Ariadne is a symbol of the Greco-Roman past.

In Greek mythology, Ariadne helped the Athenian hero Theseus to escape the Labyrinth on the Island of Crete after he slew the Minotaur. Afterwards, abandoned by Theseus, she slept on the shore waiting for love and rescue. While the conclusion to her story varies depending on the source, her desertion and subsequent melancholy became a popular source for both poetic and visual interpretation. In The Soothsayer’s Recompense, de Chirico emphasizes the statue’s despondence and isolation by taking her out of the museum and positioning her in the empty piazza. Moreover, the sculpture is significantly altered in form. Elongated and repositioned on a stark square slab, de Chirico’s Ariadne appears to sink into the stone base beneath her. The statue’s body is repositioned from reclining partially upright to lying down with both breasts exposed. Yet her head remains at the same cocked angle, framed by both her arms.

In many ways the subtle alterations of the Sleeping Ariadne statue reflect the personal significance that the Ariadne myth acquired for de Chirico during the 1910s. Born in Greece to Italian parents, the artist moved to Munich in 1905 where he became interested in the work of German philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer. De Chirico then relocated to Milan, Florence, and eventually Paris in 1911. While in Paris, de Chirico expressed his homesickness for Greece and Mediterranean culture in letters to his family. Some critics have observed resonances of this feeling of isolation in the artist’s Metaphysical Paintings. De Chirico’s identification with the Ariadne myth communicates not only a shared sense of solitude, but also offers a dreamy escape into the classical past and a retreat into de Chirico’s memories of his childhood in Greece.

Giorgio de Chirico, The Transformed Dream, 1913, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 151.8 cm (St. Louis Art Museum)

The personal nature of de Chirico’s painting is further revealed through the inclusion of the two palm trees. These trees are likely a reference to de Chirico’s Grecian childhood where he grew up surrounded by palms. Yet some scholars believe the significance of these trees to be more complex. During the early 1910s de Chirico introduced French colonial products into his paintings. Thanks to the expansive trade network established between France and its colonies in Africa and the Americas, Parisians enjoyed exotic vegetation and foods not readily accessible to much of Europe. De Chirico saw these imports for the first time in Paris and it was not long before bananas, pineapples, foreign palm varietals, and other overseas goods appeared in the artist’s paintings of the same period.

Between past and present

In The Soothsayer’s Recompense, Ariadne lies between wakefulness and sleep, between past and present. Her still, delicately draped classical form is in stark contrast to the unadorned piazza and the locomotive, a symbol of technological advancement that embodied the velocity of modernity (the speed of change driven by industrialization). The relationship between the contrasting motifs of antiquity and modernity, however, is not direct, the train is distant and the wall conceals most of it from view. Will the train stop at the station behind Ariadne? As a symbol of modernity, does the train, in some way, come to rescue the suffering Ariadne, bringing her into modern era?

Clock and train (detail), Giorgio de Chirico, The Soothsayer’s Recompense, 1913, oil on canvas, 135.6 × 180 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

The artist imbues the scene of the darkening piazza with a sense of foreboding despite the station’s clock which reads just a few minutes before two. The time of day does not line up with the sickly and darkening sky or elongated shadows. De Chirico referred to his use of exaggerated lighting as the melancholy of the beautiful autumn afternoons that he witnessed in Italian piazze in Milan, Florence, and especially Turin. With these elements de Chirico hints at the construct of time as a philosophical concept. Is it two o’clock or later? Does the clock keep time or defy it? Either way, it adds another element of suspense, surely something will happen once the clock strikes two.

Visualizing metaphysics

The desolate square in The Soothsayer’s Recompense is full of stark forms that simultaneously call to mind the simplicity of modernist design (clean lines free from ornament) and the motifs of classical architecture such as the roman arch. But this is not an actual piazza. Rather, this space utilizes architectural forms to frame Ariadne, the palm trees, the train, and the clock—uniting their disconnected symbolism within a tangible space. The combination of these forms is an attempt to visualize metaphysics—a branch of philosophy that considers what it means to transcend the physical. Metaphysics deals with abstract concepts such as being, knowing, substance, cause, identity, time, and space. This philosophy is the basis for Giorgio de Chirico’s Metaphysical works. Shying away from abstraction, de Chirico and other Metaphysical artists employed readable signs and symbols that are used in unexpected ways. The Soothsayer’s Recompense does not relay all the complexities of Metaphysics but rather encourages the viewer to reflect on the abstract concepts explored in this branch of philosophy.

Giorgio de Chirico, Ariadne, 1913, oil and graphite on canvas, 135.3 × 180.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Soothsayer’s Recompense and de Chirico’s other works of Metaphysical Painting such as Ariadne, The Disquieting Muses, and The Song of Love share visual similarities with the works of French Surrealism. Although both Surrealist and Metaphysical paintings use unexpected juxtapositions, Surrealist works attempt to visualize or activate the unconscious mind, whereas de Chirico here uses philosophy. Moreover, Metaphysical painting predates the founding of Surrealism by nearly a decade, and de Chirico did not wish to be labeled a Surrealist even as he became celebrated in Parisian circles as the “Father of Surrealism.” While the works of these two artistic movements appear visually similar, the aims of Metaphysical Painting are entirely divorced from the Freudian-inspired works of Surrealism.

Afterlives and copies

The Soothsayer’s Recompense is not the only painting by Giorgio de Chirico to feature Ariadne in a desolate piazza, merely the first of its kind. In the years that followed, the artist painted many variations of this scene in the Metaphysical style, often with additional and interchangeable symbols including towers, fountains, and the occasional shadowy or indefinite figure. The reasons behind de Chirico’s reuse of motifs, spaces, and even whole paintings is complex, but it is clear that the elements of The Soothsayer’s Recompense had personal importance for the artist.

Additional resources

Paolo Baldacci and Giorgio de Chirico. De Chirico: The Metaphysical Period, 1888–1919, 1st North American Edition (Boston: Little, Brown, 1997)

Emily Braun, eds. Giorgio de Chirico and America (New York: Hunter College of the City University of New York), 1996

Sophia Maxine Farmer, “De Chirico in New York: a Guide for Museumgoers,” La Voce di New York (June, 2017)

Sophia Maxine Farmer, “The Trouble with De Chirico: Verifalsi and the Study of Backdated Paintings.” The Brooklyn Rail (May, 2017)

Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico

Taylor, Michael R., and Guigone Rolland, Giorgio de Chirico and the Myth of Ariadne (London: Merrell, 2002)