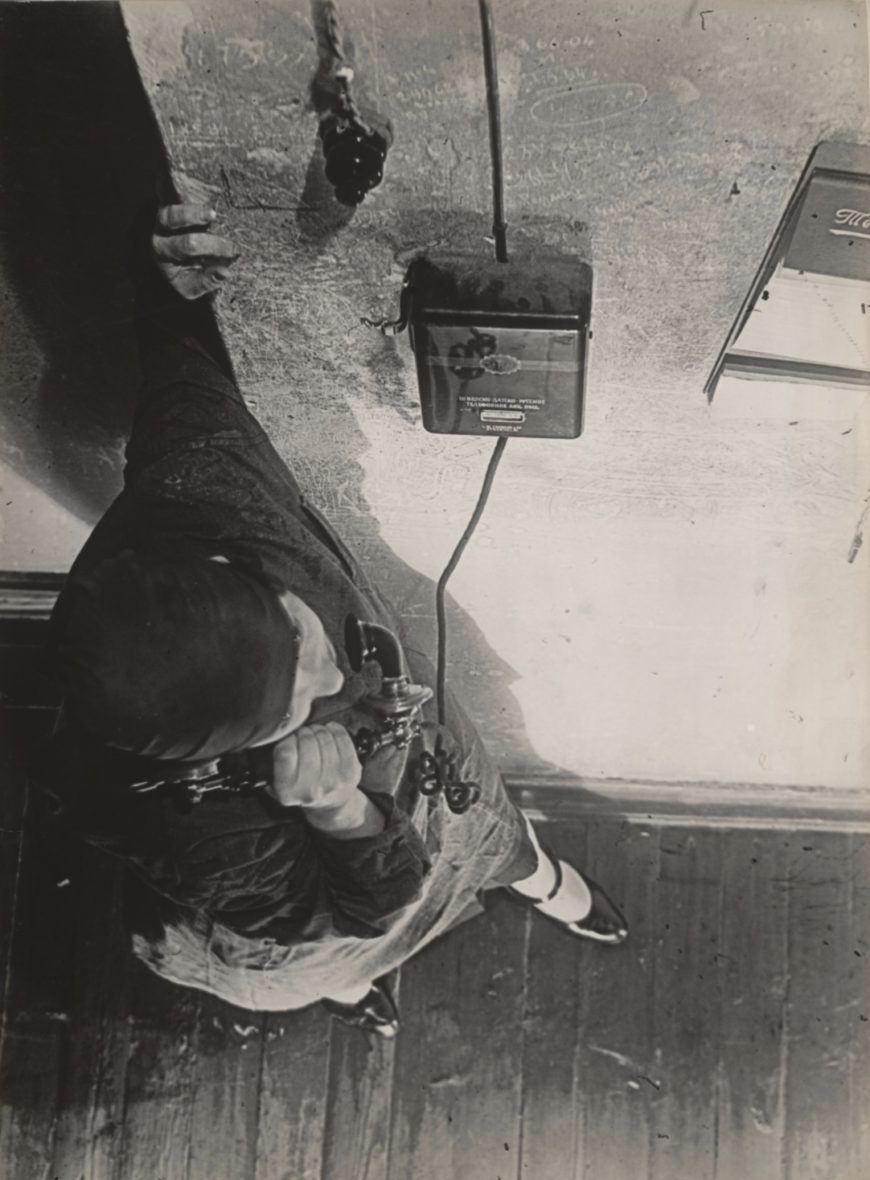

Alexander Rodchenko, At the Telephone, 1928, gelatin silver print, 39.5 × 29.2 cm (MoMA)

Alexander Rodchenko’s 1928 photograph At the Telephone shows a woman, seen from above, leaning against the wall as she speaks into the telephone. The unusual overhead perspective, the cropping (which suggests a momentary glimpse from above), and the way in which the the walls, the gleaming telephone box, and floorboards read as lines and shapes—hints at the radical nature of this photograph—and of New Vision photography.

Revolutionary Photography

In the years after the 1917 Russian Revolution and the shift to socialism, Russian Constructivist artists like Alexander Rodchenko were concerned with making a new socially productive, utilitarian art that would support the bourgeoning communist society. Under communism, the collective, rather than the individual, was the primary focus of artists, designers, and architects. Rodchenko, who previously had worked in painting and sculpture, took up photography in the mid-1920s. At this time, he was preoccupied with the following question: How does one express the idea of Revolution with the camera? [1]

One way he answered this question was by shifting the perspective. Taken from above, the radically foreshortened view of a woman on the telephone dominates the left side of the picture. We do not see her face or what she looks like, and her hands, one of which appears as disembodied fingers clutching the wall while the other grasps the new telephone, are emphasized. Strong verticals, from the floorboards to the graffitied wall and the telephone, are broken by the diagonal of the woman’s body and outstretched leg and its shiny black patent leather shoe. Stark contrasts of light and dark and a careful attention to the varied texture of elements in the frame—the shiny black shoe, the grain of the wooden floorboards, the rough texture of the wall, the gleaming black of the telephone—reveal the artist’s sharp focus on his subject. But the resulting image is abstract (similar, in fact, to his earlier abstract paintings) and remarkably flat, as if an exercise in contrast, and hard geometries.

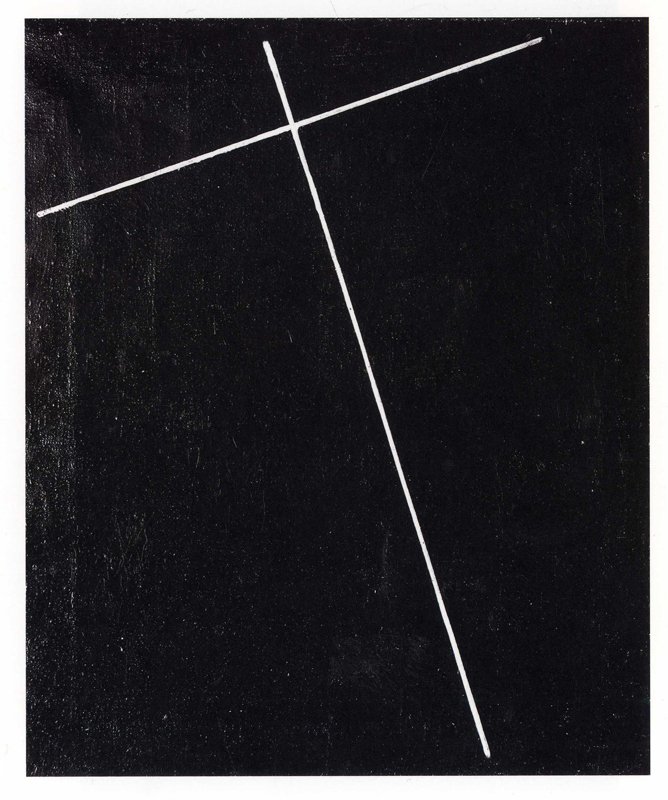

Alexander Rodchenko, Construction No. 128, 1920, oil on canvas

62 x 53 cm (Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow)

This is not your typical image of a woman on the telephone. We do not, for example, see her body straight on, in what Rodchenko disparagingly called “belly-button” photography. Instead of holding the camera at his waist (as was done with earlier cameras, like the Kodak brownie), using his handheld camera (that could be aimed from the eye, and was understood to be an extension of it) he photographed her from above. In part, this use of unusual angles, which was characteristic of his photographs from this period, was intended to force the viewer to actively engage with the image over time, because it would have taken the viewer a moment to recognize the subject due to its unexpected angle. Thus, this radical new perspective, a birds-eye view, was meant to change the viewer’s perception, to make us see the world anew and become more aware of our environment.

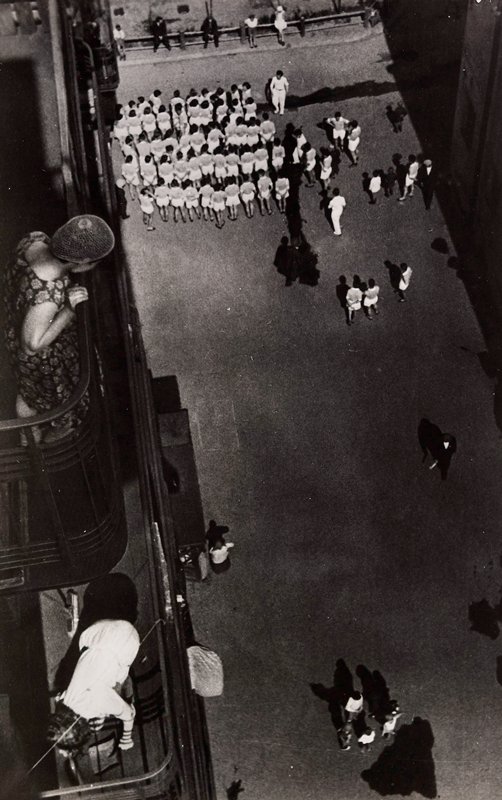

Alexander Rodchenko, Gathering for a Demonstration, 1928, gelatin silver print, 22.54 x 14.29 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Rodchenko was also concerned with the photograph’s ideological content. At the Telephone was part of a magazine story about the steps in the production of a newspaper, which sometimes involved gathering and relaying information using telephones, which were celebrated as a new technology in Russia after the Revolution in 1917. Although the Five-Year Plan—a government initiative for the rapid industrialization of the country—started in 1928, the same year as Rodchenko’s photograph, the emphasis on the role of new technologies is striking. The telephone spoke to one of the technological achievements of the Soviet state, and, as part of a magazine story, it encouraged readers to embrace progress, change, and new perspectives. At the Telephone also emphasized the participation of women in the publication of the newspaper and the use of the telephone in everyday life.

Painting is Dead and the Turn to Photography

Photography had taken on a new importance in the years after the Russian Revolution in 1917, from the use of photomontage in advertising, posters, and books, to the use of photography to promote the activities of the new regime. Photography, which involved a machine (the camera), was seen as aligned with modern world (the world of telephones, airplanes, and automobiles). But it could also be aligned with communist ideology. As reproducible media, photography and film could take the place of painting and sculpture as art forms that could reach the masses.

Earlier in the decade, artists including Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and Gustav Klucis, took up photomontage for masses-focused, utilitarian purposes that included advertising, typography, and propaganda. The institutions they were working for or with had the authority of the government or were government sponsored. Narkompros, the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment, administered all aspects of education and culture, and many of the artists, including Tatlin and Rodchenko, occupied positions in Izo (the Section of Visual Arts of Narkompros). Rodchenko also taught at Vkhutemas (the Higher State Artistic-Technical Workshops), which was the principal state art school.

This shift to photomontage signaled the rise of “Productivism” after 1921—the term used to describe the shift by Constructivist artists after 1921 to the production of utilitarian objects (posters, advertisements, kiosks, clothing) and designs for manufacturing. But Rodchenko’s engagement with photomontage lasted only a few years, and he abandoned it in 1924 when he began making still photographs.

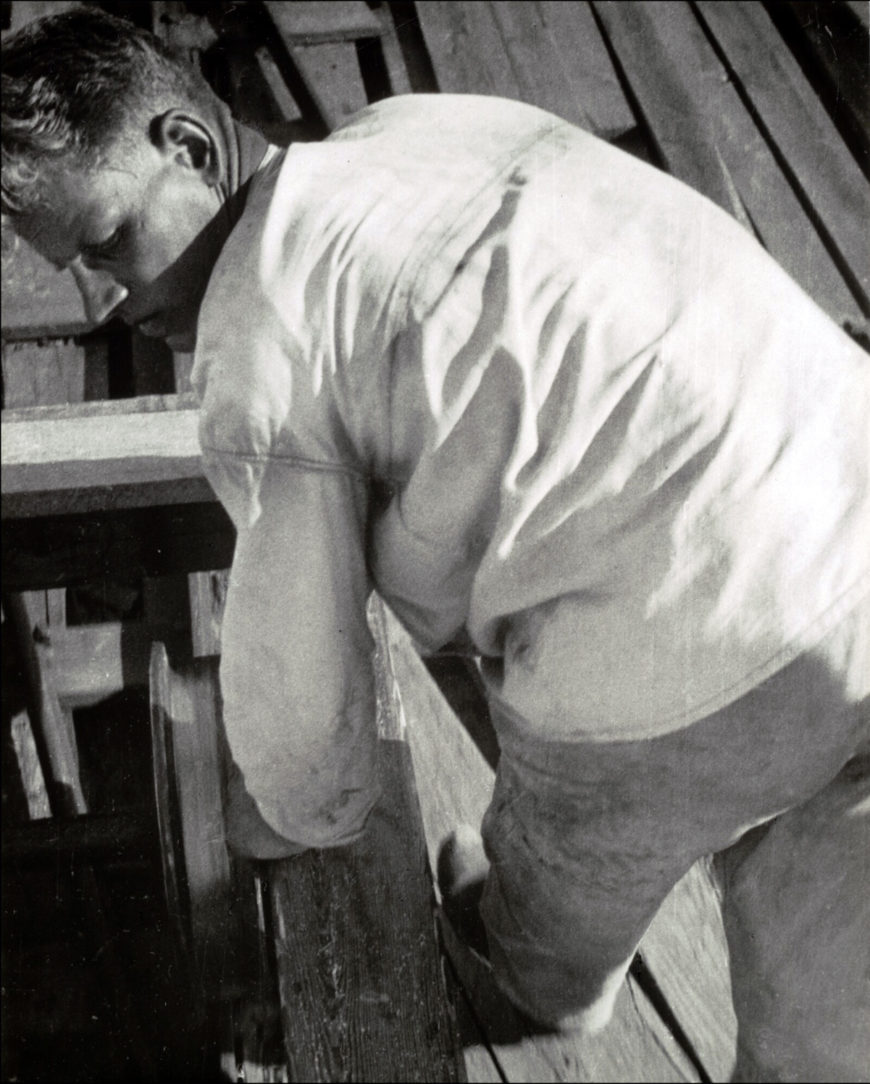

Alexander Rodchenko, Chauffeur, 1929, gelatin silver print, 29.8 × 41.8 cm (MoMA)

Not “Belly-Button” Photography

When Rodchenko purchased a handheld camera in Paris in 1925, he sought out new ways to create meaningful work that moved beyond traditional approaches to photography. After the formation of the magazine New Left (1927–28), which was extensively illustrated with photographs, Rodchenko took on a prominent role as designer and photography editor. At the Telephone ran in issue 11 (1928). He had already written a series of essays that detailed his views on photography and its role in society in issue five (1928):

Photography possesses old points of view, those of man standing on earth and looking straight ahead. What I call ‘shooting from the belly button’— with the camera hanging on one’s stomach.

I am fighting against this standpoint and shall continue to do so, as will my comrades, the new photographers.

Photograph from all viewpoints except “from the belly button,” until they all become acceptable.

The most interesting viewpoints today are “from above down” and “from below up,” and we should work at them. . . I want to affirm these vantage points, expand them, get people used to them. Alexander Rodchenko [2]

For Rodchenko, these new angles would encourage active viewing and expand our perception of the world around us.

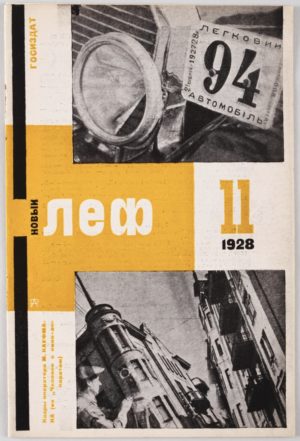

Aleksandr Rodchenko, Novyi LEF. Zhurnal levogo fronta iskusstv, 11, 1928, letterpress, 22.9 x 15.3 cm (MoMA)

Despite Rodchenko’s revolutionary approach to photography, he was accused (in 1928, the same year he made At the Telephone) in the pages of Soviet Photography of being more concerned with style over substance, and with plagiarizing avant-garde artists like László Moholy-Nagy. Although he defended himself in a series of written rebuttals, official state-sanctioned photography had shifted away from Rodchenko’s radical viewpoints to prefer optimistic and naturalistic views of Soviet life referred to as Socialist Realism. The government argued that Socialist Realism could be easily understood by workers, many of whom were illiterate.

Toward the end of the 1920s, Rodchenko began to focus on photo-essays, many of which valorized labor (such as Sawmill Worker). At the Telephone was made in 1928 before he consciously switched to photojournalism around 1929, but it reveals his ongoing interest in depicting the rapidly changing world (of newspapers, cameras, and telephones) in new and unexpected ways. His favored viewpoints, from above or below, were made possible, not coincidentally, by the introduction of handheld cameras (a new technology) in the mid-1920s.

Notes

[1] For more on “Revolutionary Photography” see: Christina Lodder, “Revolutionary Photography,” in Mitra Abbaspour, Lee Ann Daffner, and Maria Morris Hambourg, eds. Object:Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection 1909–1949. An Online Project of The Museum of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014).

[2] Alexander Rodchenko, “Downright Ignorance or a Mean Trick?” in Christopher Phillips, ed., Photography in the Modern Era (New York: Aperture, 1989), p. 246.

Additional resources:

Museum of Modern Art, New York. Interactive Feature: Aleksandr Rodchenko (1998)

Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983)

The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932 (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1992)