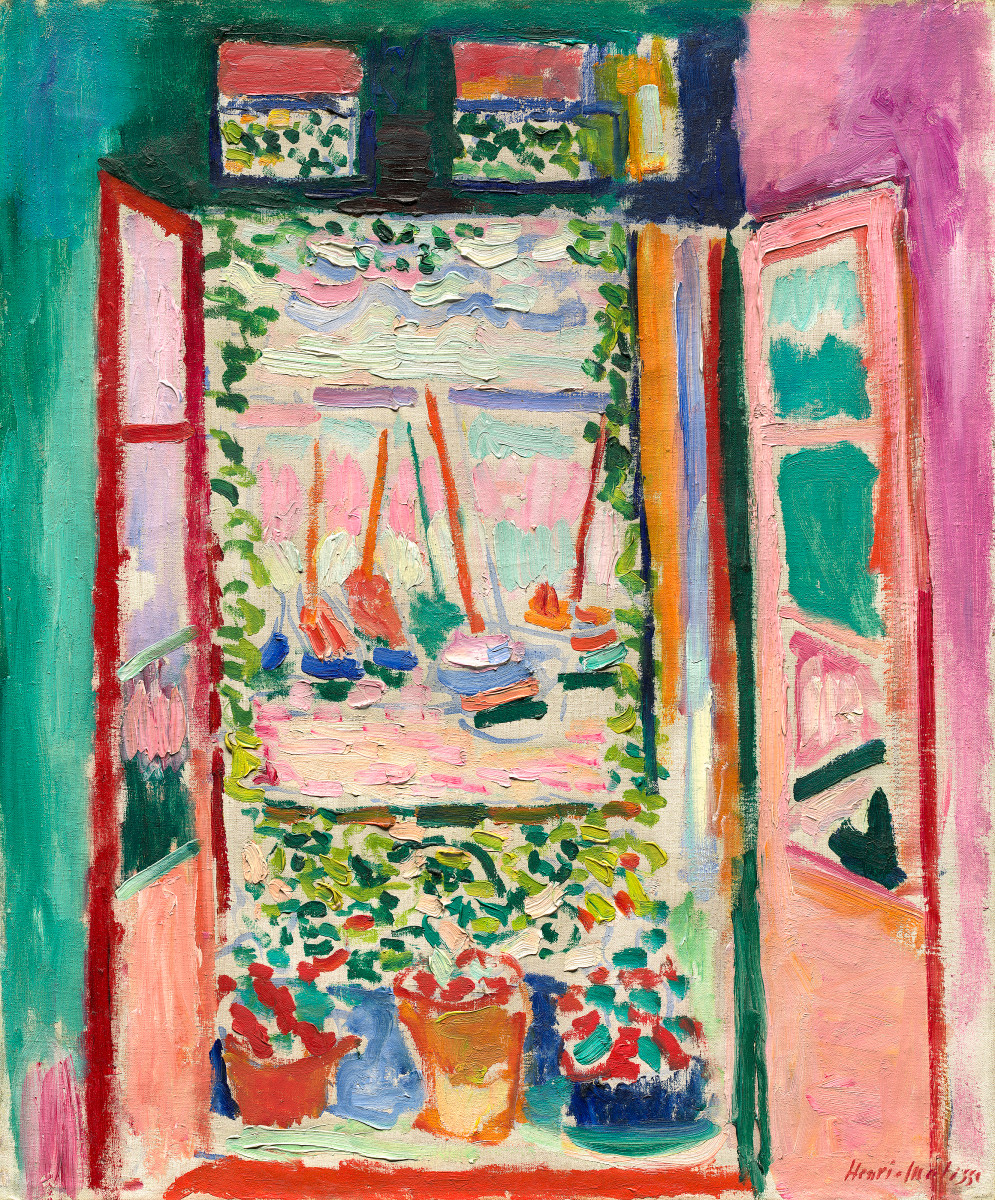

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, oil on canvas, 55.3 x 46 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington)

An explosion of color

In Henri Matisse’s Open Window, Collioure the casements of a large French window project toward us to reveal an explosion of brilliant Mediterranean color. The paint is applied very loosely; even in reproduction we can see almost every brushstroke. The painting looks as if it were made yesterday, and in some places (like the lower right where bare canvas is visible), seems unfinished. We can envision Matisse’s working process brushstroke by brushstroke, and we are there with him responding with excitement to the wealth of color and light at a Mediterranean seaside town in summer.

Although the style implies a rapid or even slipshod painting process, Open Window, Collioure was carefully orchestrated in every aspect, from the composition to the color relationships and the paint application. The window is placed slightly off center to the left, which gives the composition a casual feeling, in keeping with the slapdash quality of the brushstrokes. Underpinning this seeming casualness, however, is a calculated structure of repeating and nested rectangles that creates both a strong surface pattern and a series of internal “windows.”

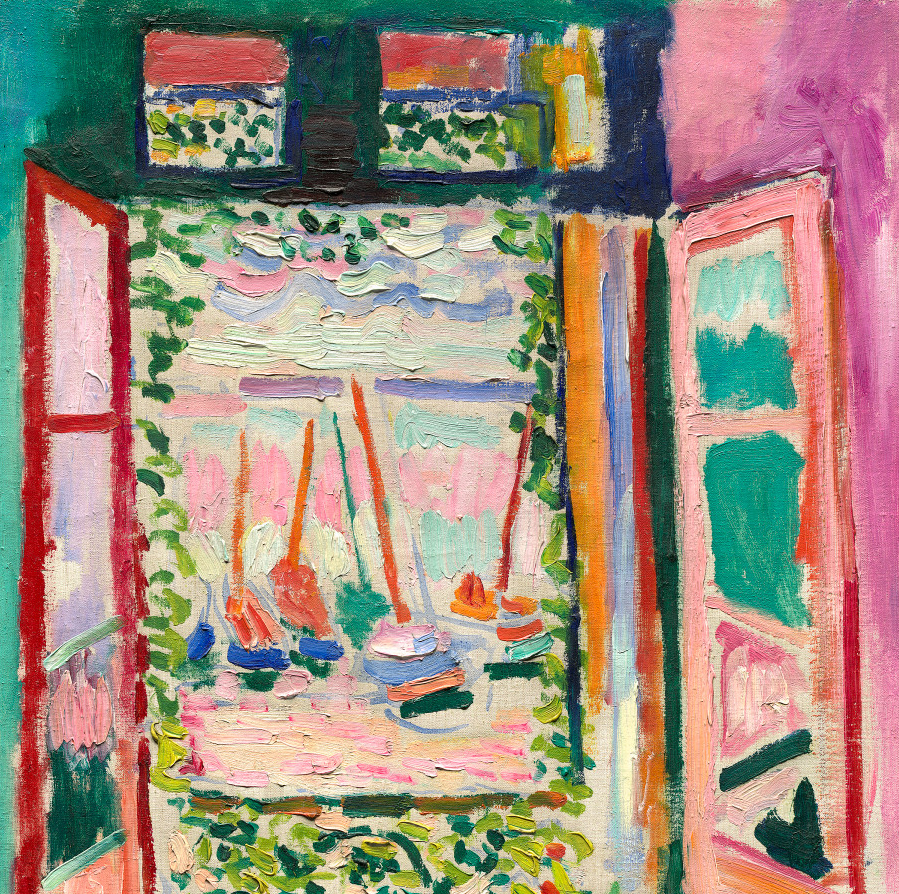

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, detail, 1905, oil on canvas, 55.3 x 46 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington)

The brightest area of the painting, the central view of boats in harbor, is framed by some of the painting’s darkest tones in both the literal window frame and a pattern of green leafy vines. Surrounding this central view are multiple subsidiary window panes. Two transom windows at the top frame more views of the porch window and vines. Glass panes in the casement windows reflect both the view outside the French window and the colors of the walls.

Brilliant colors ricochet and echo across the canvas. Matisse uses complementary color contrasts throughout, setting off his glowing reds and pinks with cool greens. The walls are fuchsia and green, and the upper window panes of the casements reflect the opposing wall’s color, enhancing the intensity of the hues by contrast. A similar mutually intensifying contrast of colors appears where the vertical stripe of vivid orange paint, perhaps representing a curtain, is brushed next to the dark ultramarine strip of the window frame. Varied patterns of pale pink and turquoise brushstrokes represent sea and sky in the view out the window.

Denying the illusion of depth

Open Window, Collioure engages with, and ultimately undermines, the post-Renaissance conception of a painting being like a window. Matisse’s drawing of the window emphasizes its role as a framing device located in a three-dimensional space. The casements open inward, creating a perspectival view leading to the window opening. The balcony with flower pots on the floor is a shallow intermediate space between the room and the view of the harbor, which reaches to the horizon. However, all of these indications of spatial depth are negated by color and paint application, which emphasize the flat surface of the canvas and fail to create a convincing illusionistic scene. We never forget that we are looking at a painting and not out a window.

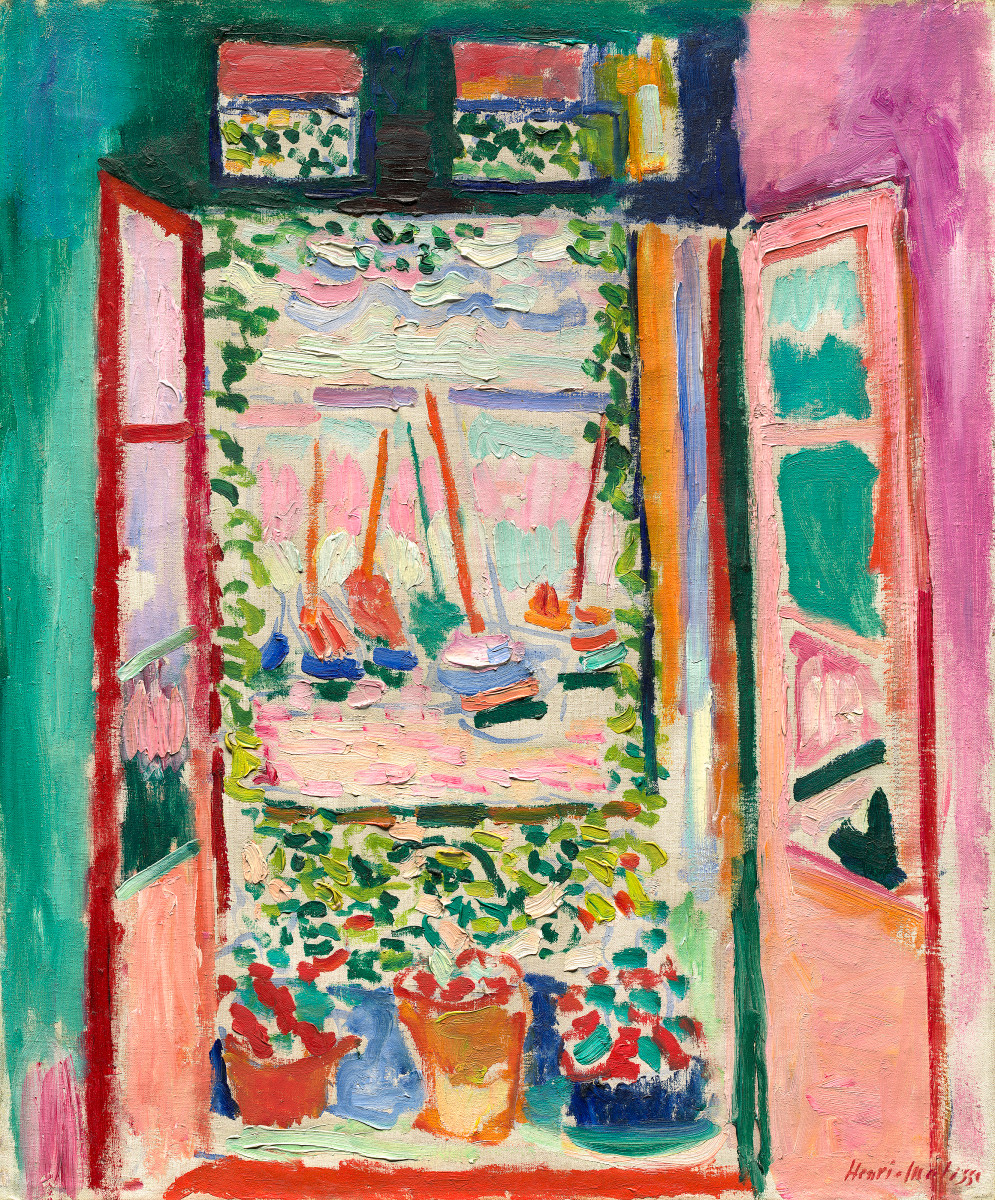

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, oil on canvas, 55.3 x 46 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington)

The highly visible brushstrokes and areas of unpainted canvas are the most obvious way Matisse denies us the illusion of reality, but his use of color is also important. Not only is it extremely bright and flat, lacking the chiaroscuro modulations traditionally used to suggest volume and depth, it also repeatedly subverts clear differentiation of foreground and background. For example, the distant masts of the boats in the harbor and the much closer verticals of the window frames create a surface pattern of bright orange and red verticals. The more distant reds and oranges are not muted to indicate depth through atmospheric perspective. Similarly, the dark blue and green brushstrokes depicting the hulls of the boats are echoed by the dark blue and green paint strokes used to indicate edges of the window frames and various objects in the foreground.

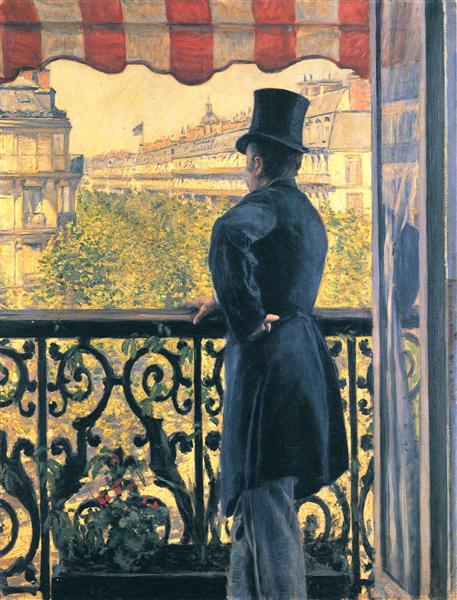

Gustave Caillebotte, Man on a Balcony: Boulevard Haussmann, 1880, oil on canvas, 116 x 89 cm (Private Collection)

A glance at Gustave Caillebotte’s compositionally similar Man on a Balcony: Boulevard Haussmann shows how completely Matisse undermines the depiction of perspectival depth. Caillebotte’s naturalistic scene clearly distinguishes between the darker dominating foreground space of the balcony and the vista of sunlit buildings receding down the boulevard. In Matisse’s Open Window, Collioure, the distant harbor view dominates, and it is framed by the window as if it were itself a painting. It has no defined spatial relationship to the foreground, unlike Caillebotte’s vista down the boulevard where we can determine the relation of the balcony to the view with precision.

The 1905 Salon d’Automne

Open Window, Collioure was one of several paintings Matisse exhibited with a group of friends at the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris. A sympathetic art critic, Louis Vauxcelles, inadvertently named the group when he described the effect of their brilliantly colored paintings hanging on the walls surrounding two classicizing sculptures as being like Donatello among the fauves (wild beasts). The name came to reflect the extreme public reaction to the paintings, which were widely considered disturbing and outrageous. Conservative critics mocked the paintings in the press, but the Fauve painters ultimately profited from the notoriety and found dealers, critics and collectors who supported their work.

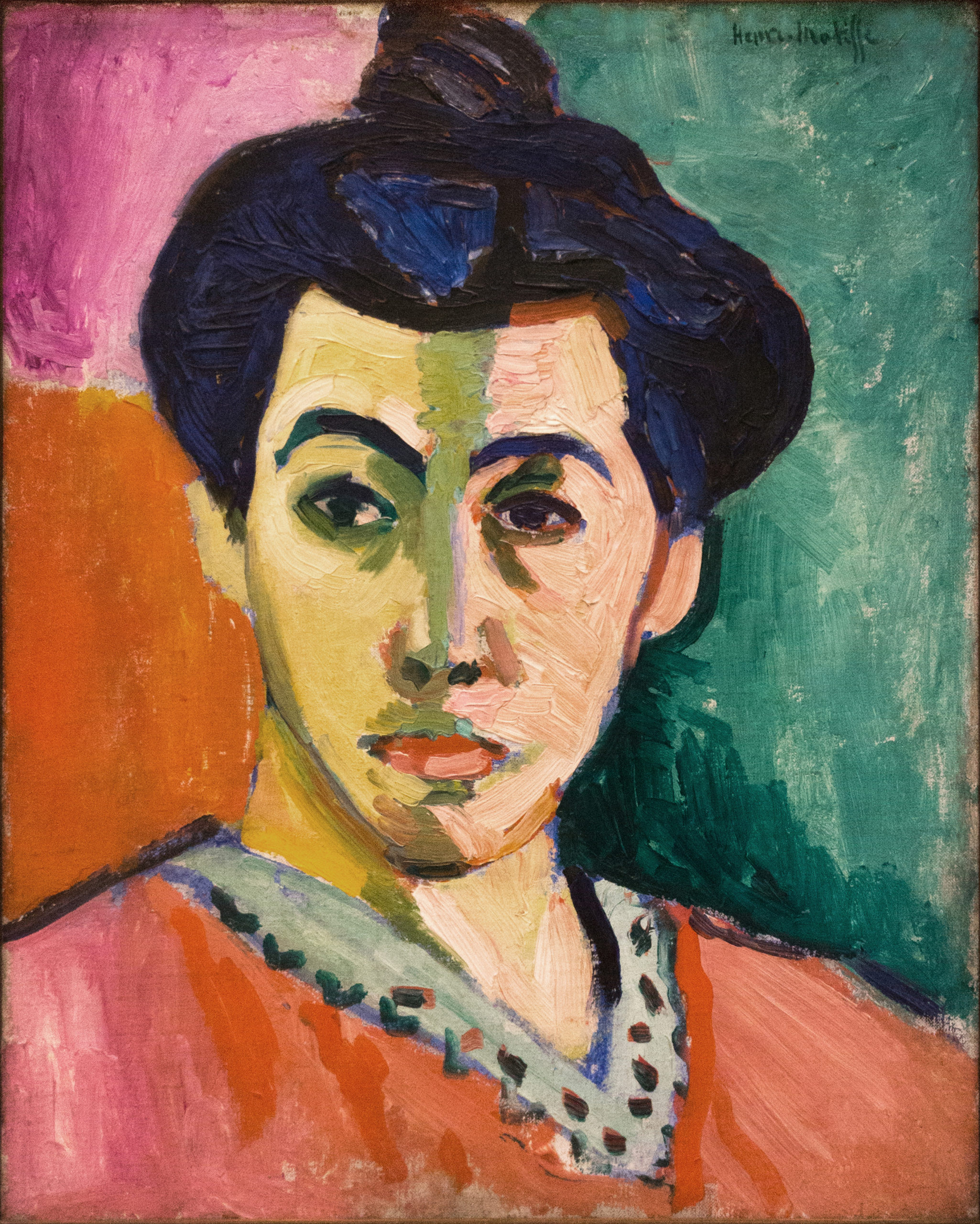

Henri Matisse, Woman with a Hat, 1905, oil on canvas, 80.6 x 59.7 cm (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

Matisse was the leader of the group, and his Woman with a Hat was considered the most scandalous painting in the “fauve cage” at the exhibition. The use of brilliant complementary colors, prominent brushwork and seemingly unfinished areas is very similar to Open Window, Collioure, but their effect in this traditionally-composed portrait of a woman was unsettling.

Left: Berthe Morisot, Summer’s Day, detail, c. 1879, oil on canvas, entire painting 45.7 x 75.2 cm (The National Gallery, London); Right: Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1899, oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

The crude dabs of paint, harsh simplified features, and the rendering of the shadows on the face in brilliant turquoise were all startling, even for viewers used to the painterly abbreviations and bright colors of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The faces in Morisot’s Impressionist Summer’s Day, and van Gogh’s Post-Impressionist Self-Portrait lack realistic detail and call attention to the artists’ brushstrokes, but the color used in both paintings remains well within the range of naturalistic depiction compared to Matisse’s Woman with a Hat.

In addition to the aggressively non-naturalistic tones in the face, Matisse’s style in The Woman with the Hat is raw and disjunctive. The painting looks unfinished and unresolved, with some parts painted in heavy impasto and others barely brushed in. The Salon jury tried to persuade him to retract the painting from his submission, but Matisse refused, indicating that he believed the painting to be finished and ready for exhibition.

The expressive potential of color

Henri Matisse, Portrait of Mme. Matisse: The Green Line, 1905, oil on canvas, 40.5 x 32.5 (Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen)

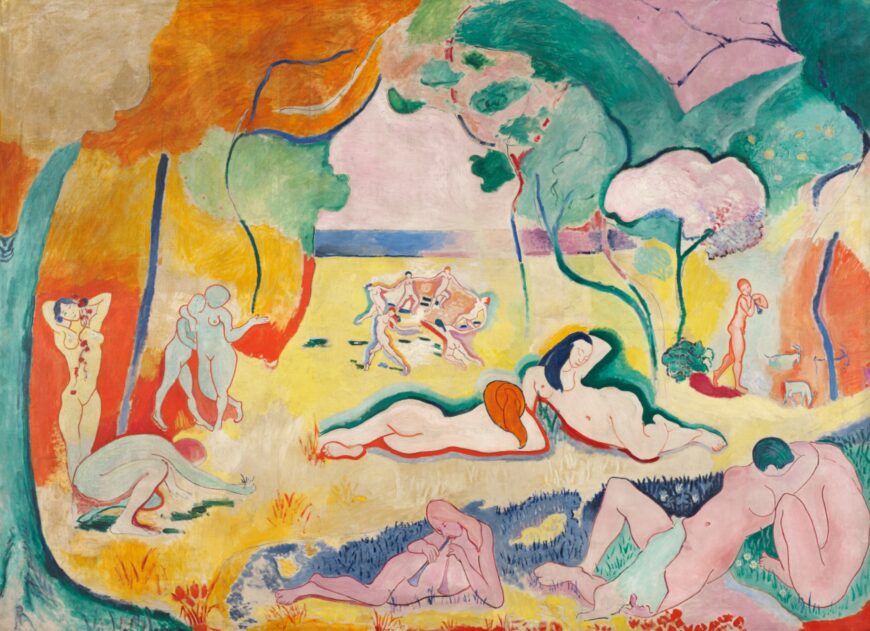

Matisse’s paintings in the 1905 Salon d’Automne with their disjunctive brushwork and tempestuous color were his most radical Fauve works. After the exhibition, Matisse continued to use bright non-naturalistic color, but his paint application became more consistent and his colors less chaotic. In Portrait of Mme. Matisse: The Green Line and Bonheur de Vivre the brilliant colors are organized into larger areas to maximize their intensity. Over the course of the next few years he became increasingly concerned with pictorial harmony.

Henri Matisse, Bonheur de Vivre, 1906, oil on canvas, 175 x 241 cm (Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia)

In his 1908 “Notes of a Painter” Matisse wrote:

The entire arrangement of my picture is expressive . . .. Composition is the art of arranging in a decorative manner the diverse elements at the painter’s command to express his feelings. In a picture every part will . . . play its appointed role. . . . A work of art must be harmonious in its entirety. . . .Henri Matisse, “Notes of a Painter,” [1908] trans. J. D. Flam, in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory 1900-2000 (London: Blackwell, 2003), pp. 70-71.

Throughout his career Matisse was dedicated to the expressive potential of color: “My choice of colors is based on observation, on sensitivity, on felt experiences. . . . I simply try to put down colors which render my sensation . . . a moment comes when all the parts have found their definite relationships . . ..”[1]

Although “Notes of a Painter” was written some years after Matisse painted Open Window, these passages indicate that he was balancing three different projects. He was attempting to be responsive to (1) the perceptual information he received from the motif, (2) the feelings that he got from it, and (3) the decorative formal qualities of the work of art itself. Keeping all three in play allows The Open Window to read simultaneously as a window into real space, a flat plane covered with harmonious color, and an expression of the joyful warmth of a Mediterranean day.

Henri Matisse,Open Window at Collioure, 1914, oil on canvas, 116.5 x 89 cm (MNAM – Centre Pompidou, Paris)

The Open Window was one of Matisse’s most radical Fauve paintings, but it is also an example of his enduring dedication to expressive color and pictorial harmony. Matisse painted many windows throughout his career, including The Blue Window and The Piano Lesson, and they reflect the variations in his style over time. The Open Window of 1905 represents the barely restrained exuberance of his Fauve period, while a second version of Open Window at Collioure painted in September 1914 just after the start of World War I conveys the mood of those dark days.

Notes:

- Henri Matisse, “Notes of a Painter” [1908], trans. J. D. Flam, in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory 1900-2000, (London: Blackwell, 2003), pp. 70-71.

Additional resources:

The Open Window, Collioure at the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC