Chrysler Building, photo: David Shankbone, CC: BY-SA 3.0

With its sky-piercing spire, its sleek, metallic ornament poking out over the streetscape, and its luxurious marble- and metal-lined interiors, the Chrysler Building epitomizes its time: an era of concentrated wealth, industrial power, and large-scale city building. It is often said that architecture is a measure of civilization. If so, there may be few better artifacts of the short-lived epoch called the Roaring Twenties than the Chrysler Building. Ironically, the Art Deco Chrysler Building also marked the end of that dizzying period.

Race to the top

In 1927, Architect William Van Alen received a commission for an office tower from real-estate developer William H. Reynolds. It was to be 808 feet tall with a crowning glass dome meant to “give the effect of a great jeweled sphere.” With mounting costs, Reynolds sold the lease in late 1928 to Walter P. Chrysler, who had formed his automobile manufacturing company in Detroit three years earlier and wanted to make a visible statement about his newfound prominence in business—he said the building would be “dedicated as a sound contribution to business progress.” Chrysler asked Van Alen to make his tower the tallest building in the world, but this was no singular act of hubris on Chrysler’s part. Both men had an interest in making the Chrysler Building as tall, glamorous, and unique as possible.

In the late 1920s, New York’s architects and developers were caught in a race to construct ever-taller buildings. By 1929, the Bank of Manhattan Trust Building on Wall Street (927 feet tall) was set to become the world’s tallest, displacing Cass Gilbert’s Woolworth Building (792 feet tall), which had held the honor since 1913. Several other buildings going up in the late 1920s near Wall Street also aimed for distinction and height.

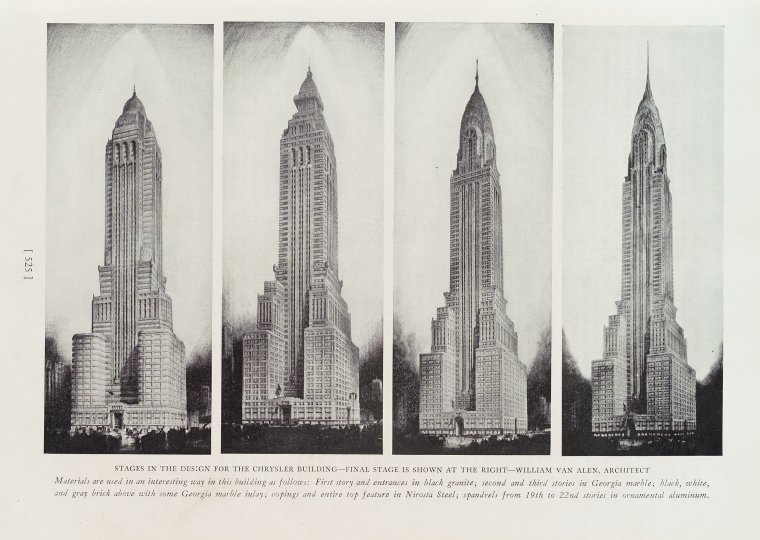

Stages in the design for the Chrysler building, Progressive Architecture, v. 10, July-Dec 1929, page 525

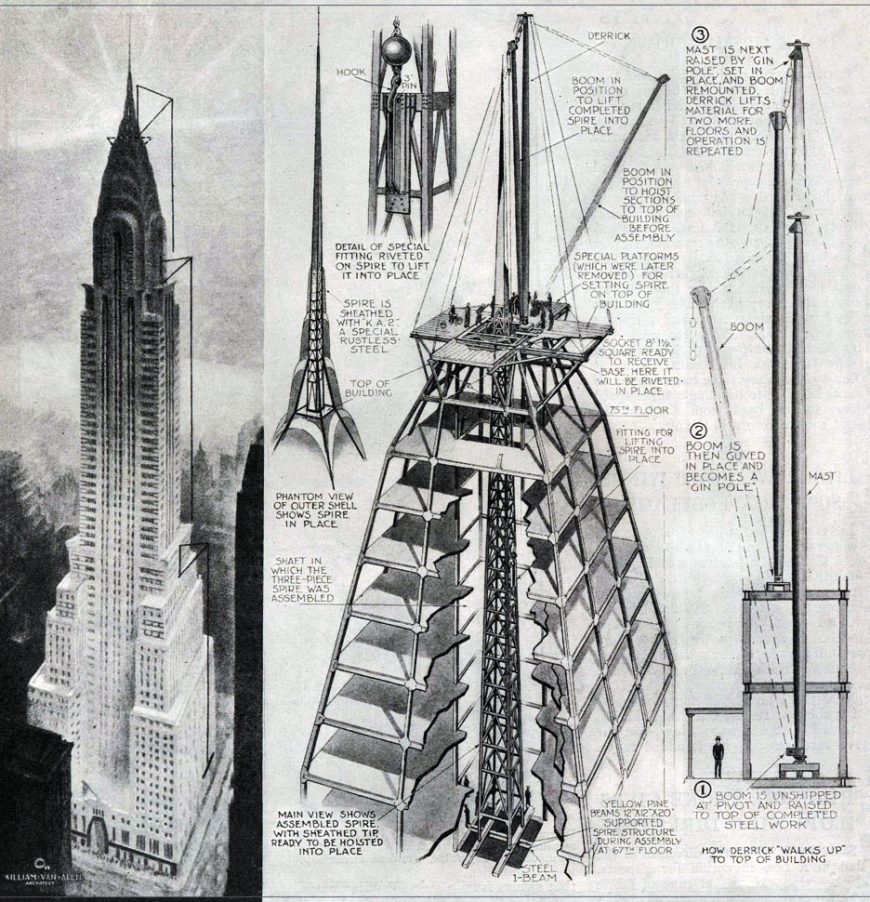

Chrysler Building Spire mechanism, Popular Science Monthly, August 1930, page 52

The competition for the tallest building was fiercest between Van Alen and his former business partner, Craig Severance (architect of the Bank of Manhattan Trust Building along with Yasuo Matsui). In the end, Van Alen triumphed: in secret, he had the 185-foot spire of the Chrysler constructed in sections and assembled inside the building, then hoisted up and through the top (diagram right) only after Severance’s Bank of Manhattan Trust tower had reached its full height in November 1929. With the spire, the Chrysler now reached 1,046 feet. It claimed the title of world’s tallest building from its official completion on May 27, 1930, until the completion of the Empire State Building on April 11, 1931.

The Chrysler Building’s overall shape and composition put it into a distinctive local tradition of skyscraper design. New York architects developed a particular way of handling New York City’s 1916 zoning resolution known as the “setback” law. Although not all skyscrapers followed the model, it was a popular formula: a broad base on top of which rose a slender tower, often incorporating setbacks at multiple levels, all topped by a pyramidal cap or spire. Important examples include the Manhattan Life Insurance Building (completed 1894), the Singer Building (1908), the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower (1909), the Woolworth Building (1913), and, of course, the Bank of Manhattan Trust (1930), Chrysler (1930), and Empire State Building (1931).

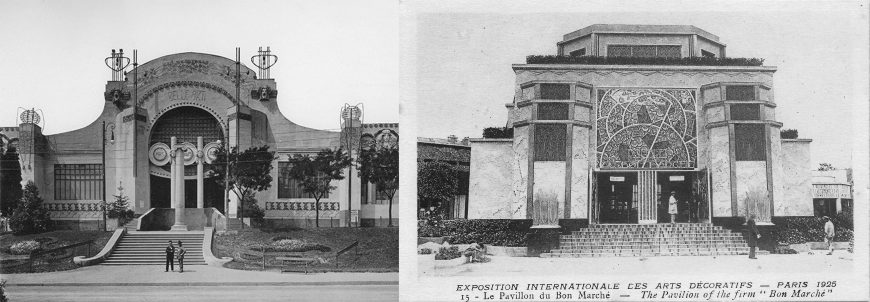

Left: Art Nouveau architecture, Fine art building, Prima Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Decorativa Moderna, Turin, 1902; right: Art Deco architecture, Pavillon du Bon Marché, Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes de Paris en 1925, postcard, Les Éditions artistiques LIP : Paris & ses Merveilles – imprimeur: J. Cormault à Paris, 1925

Art Deco

The Chrysler Building’s style—Art Deco—was considered modern, urbane, and luxurious. The term itself originated from the Exposition internationale des Arts Décoratifs et industriels modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts), held in Paris in 1925 (above right), but the roots of the style went back further. Art Deco could describe everything from the style of a corporate office tower (such as the Chrysler Building), to the decorative pattern on furniture, murals, and tilework. The style incorporated chevron, sunburst, fountain, and arc motifs, endless varieties of geometric patterns, and, in later instances especially, cubic and machine-like forms. It was generally more rectilinear than the swirling floral and vegetal patterns common in the earlier Art Nouveau (above left), and was quite distinct from the forms and details of classical Beaux-Arts architecture and ornament, which was prominent in the early twentieth century.

Automobile friezes in the brickwork, photo: cogito ergo imago, CC: BY-SA 2.0

It would be an exaggeration to say that Art Deco fully rejected the Art Nouveau or the Beaux-Arts styles; instead, Art Deco designers synthesized and abstracted earlier motifs and patterns to create a decorative layer on buildings laid out in otherwise conventional ways. In New York, Art Deco exteriors ran a spectrum from the ornate to the spare (the Chrysler falls in the middle range of that spectrum). Interiors, however, tended to be colorful and lively, with marble and metal details in color schemes dominated by gold, silver, black, red, and green.

Eagle, Chrysler Building, 1931, photo: Jason Eppink, CC: BY 2.0

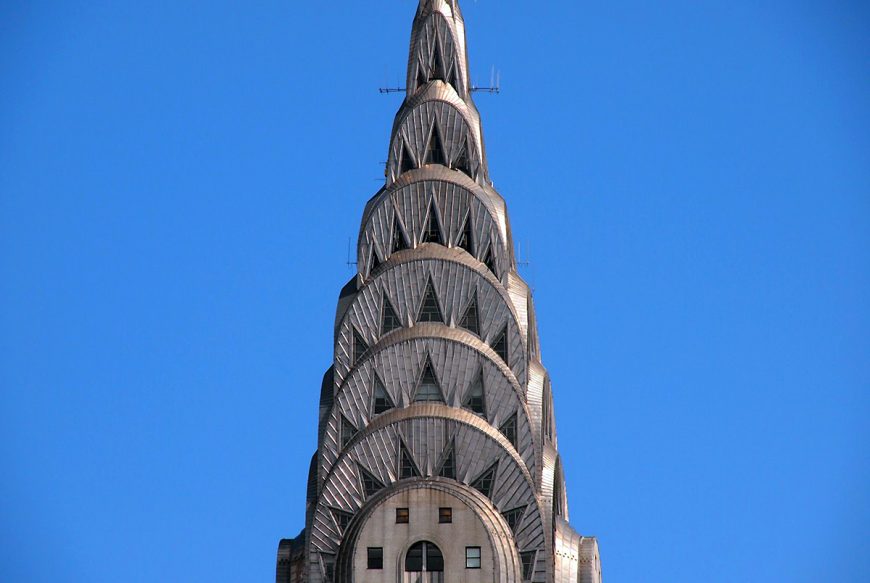

At the Chrysler Building, the distinctive elements of Art Deco include the horizontal black-and-white stripes between floors, the geometric decoration concentrated at each of the setbacks, the streamlined eagle heads and radiator caps with wings (referencing the hallmark Chrysler car ornaments) jutting out from the corners, and, above all, the great crown with its seven layers of crescent setbacks inset with triangular windows. Brightly lit at night, the crown is still one of the most distinctive elements on the New York City skyline. Although the ground-level experience is often described as lackluster, the building’s contribution to the skyline is its true achievement. It made the Chrysler Building a symbol of urban modernity, of New York’s business dynamism, and of the vibrant nightlife of the world’s newest metropolis.

Depression and Modernity

The stock market crashed on October 29, 1929, in the midst of the Chrysler Building’s construction. This initial shock did not immediately lead to the economic ruin of the Great Depression—that set in a few years later. However, the glamour, economic growth, and optimism associated with the Roaring Twenties was over. For some, the Chrysler Building came to be a symbol of a lost, hedonistic era, having resulted from the same supposedly rational economic decisions that had led to the market crash. However, some commentators in the 1930s also suggested the building’s lights and upward thrust be seen as symbols of hope for a better future.

Detail, Edward Trumbull, Transport and Human Endeavor, oil on canvas attached to lobby ceiling, 1930

The 1920s was a decade of great wealth disparities. Rich bankers and industrialists, including Walter Chrysler, had done very well. They used their patronage of architecture to convey their high status and the power some believed rightly accrued to those who had prospered in the system of American industrial capitalism. One could argue that the Chrysler Building’s height, glamour, and prestige was concocted to celebrate one man whose wealth was the result of huge profits he accrued at the expense of poorly paid laborers and other workers.

Chrysler Building Spire, photo: Paul Arps, CC: BY 2.0

But few buildings are only about one person. A huge building like the Chrysler cannot help but also be a monument in the city that surrounds it, and as such it helped fix for decades to come New Yorkers’ understanding of their city as stylish and forward-looking. After the depression and World War II, New York City became the world’s foremost cultural center. And the Chrysler Building was still there, glimmering high above almost everything else as a beacon and symbol of the city’s persistent optimism.