Jackson Pollock, One: Number 31, 1950, 1950, oil and enamel paint on unprimed canvas, 269.5 x 530.8 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Painters in Postwar New York City

The end of World War II was a pivotal moment in world history and by extension the history of art. Many European artists had come to America during the 1930s to escape fascist regimes, and years of warfare had left much of Europe in ruins. In this context New York City emerged as the most important cultural center in the West. In part, this was due to the presence of a diverse group of European artists like Arshile Gorky, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalì, Piet Mondrian, and Max Ernst, and the influential German teachers Josef Albers and Hans Hofmann (see also Black Mountain College). American artists’ exposure to European modernist movements also resulted from the founding of the Museum of Modern Art (1929), the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (later the Guggenheim Museum, 1939), and galleries that dealt in modern art, such as Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century (1941). Both Americans and European expatriates joined American Abstract Artists, a group that advanced abstract art in America through exhibitions, lectures, and publications.

These institutions and the art patrons affiliated with them actively promoted the work of New York City artists. During the 1940s and ’50s, the scene was dominated by the figures of Abstract Expressionism, a group of loosely affiliated painters participating in the first truly American modernist movement (sometimes called the New York School), championed by the influential critic Clement Greenberg. Abstract Expressionism’s influences were diverse: the murals of the Federal Art Project, in which many of the painters had participated, various European abstract movements, like De Stijl, and especially Surrealism, with its emphasis on the unconscious mind that paralleled Abstract Expressionists’ focus on the artist’s psyche and spontaneous technique. Abstract Expressionist painters rejected representational forms, seeking an art that communicated on a monumental scale the artist’s inner state in a universal visual language.

Action Painting

These painters fall into two broad groups: those who focused on a gestural application of paint, and those who used large areas of colour as the basis of their compositions. The leading figures of the first group were Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner, and above all Jackson Pollock. Pollock’s innovative technique of dripping paint on canvas spread on the floor of his studio prompted critic Harold Rosenberg to coin the term action painting to describe this type of practice. Action painting arose from the understanding of the painted object as the result of artistic process, which, as the immediate expression of the artist’s identity, was the true work of art. Helen Frankenthaler also employed experimental techniques by pouring thinned pigments onto untreated canvas.

Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950-51, oil on canvas, 242.2 x 541.7 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Color Field Painting

The second branch of Abstract Expressionist painting is usually referred to as Color Field painting. Two central figures in this group were Mark Rothko, known for canvases composed of two or three soft, rectangular forms stacked vertically, and Barnett Newman, who, in contrast to Rothko, painted fields of colour with sharp edges interrupted by precise vertical stripes he called “zips” (see Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950–51). Through the overwhelming scale and intense colour of their canvases, Colour Field painters like Rothko and Newman revived the Romantic aesthetic of the sublime.

Influence

Because of the huge influence of Abstract Expressionism in postwar New York City, other artists and movements are generally understood in relation to it. Ad Reinhardt in the early 1950s and then Frank Stella later in the decade painted abstract canvases, but rejected the Abstract Expressionist emphasis on gesture and the painting as a means of communing with the artist (see Stella’s Die Fahne Hoch!, 1959). They instead reinforced the essence of the painting as a physical object through precise geometric forms and smooth application of paint, presaging Minimalism.

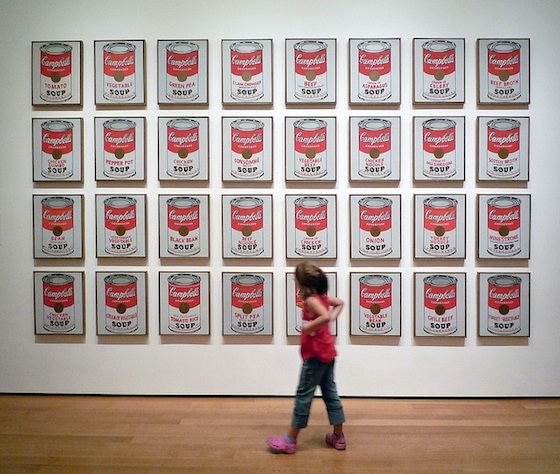

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962, synthetic polymer paint on thirty-two canvases, each 50.8 x 40.6 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

The other principal movement of postwar New York was Pop art. Although Pop had begun in England (see, for example, Richard Hamilton), postwar America provided a meaningful context for the movement’s emphasis on mass media and consumer culture. American adherents also saw Pop art as a welcome alternative to pure abstraction. The artists Jasper Johns and his close friend Robert Rauschenberg rejected Abstract Expressionism’s attachment to the universal meaning expressed in a work of art, instead creating multiple or fluid meanings through combinations of everyday objects and images. Johns depicted “things the mind already knows,” such as American flags, targets, numerals, and beer cans, and incorporated newsprint and plaster casts into his works (see Target with Four Faces, 1955). Rauschenberg also blurred the boundaries between painting and sculpture with his combines, such as Bed of 1955. These works are related to both assemblage and collage in their use of found three-dimensional objects (bedding, furniture, taxidermied animals) and layering of printed material (product packaging, newspaper, photographs) on painted surfaces.

Both Johns and Rauschenberg provided a critical departure from the pure abstraction of the dominant painters of the 1950s, setting the stage for the flourishing of Pop art in the ’60s. Andy Warhol was unquestionably the central figure of the American Pop art movement. He first worked as a highly successful advertising artist in New York before exhibiting paintings and silkscreen prints beginning in the early 1960s. Best known for his images of Campbell’s soup cans, Coke bottles, and American public figures, Warhol’s work seems to celebrate icons of consumer culture – both actual products and celebrities who were marketed and sold as such, like Marilyn Monroe – but is also often interpreted as a critique of passive, unthinking consumption. James Rosenquist, a contemporary of Warhol, also took inspiration from his work in advertising as a billboard painter. His huge canvases depicting images from print media and advertisements, such as Marilyn Monroe I (1962), are rooted in the vulgarity of contemporary life, but reminiscent of Surrealism in their juxtaposition of disparate, fragmentary imagery.

The success of abstract and Pop painters in postwar New York established the city’s international importance as an artistic center, in the ensuing decades drawing to it some of the world’s most talented and innovative artists.

Text by Kandice Rawlings, PhD (Associate Editor, Oxford Art Online)

This content was first developed for Oxford Art Online and appears courtesy of Oxford University Press.