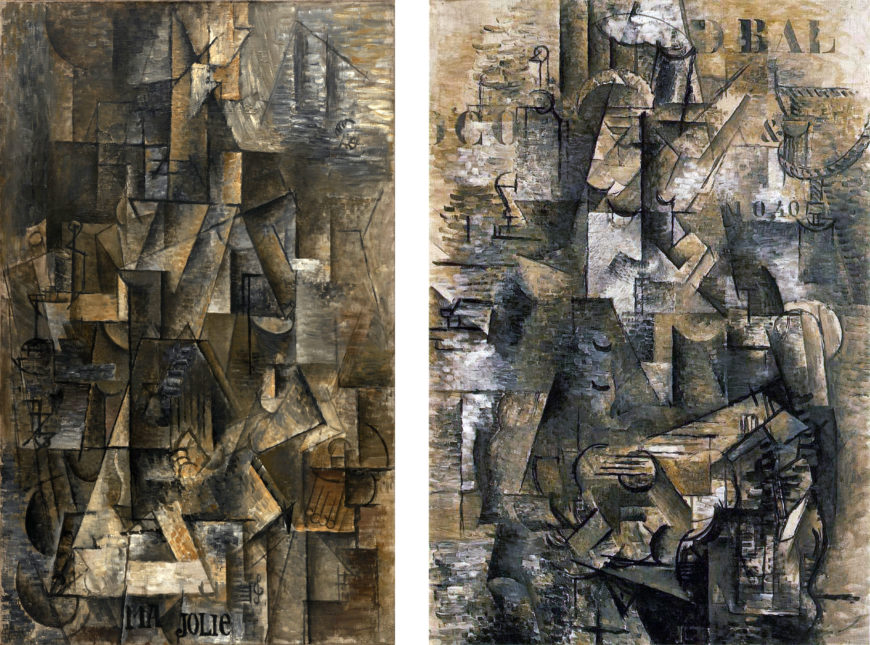

Left: Pablo Picasso, I, 1911–12, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 25 3/4 inches (MoMA); Right: Georges Braque, The Portuguese , 1911–12, oil on canvas, 46 x 32 inches (Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland)

The Portuguese and Ma Jolie are well-known examples of late Analytic Cubism , sometimes called High Analytic Cubism or Hermetic Cubism. The latter name refers directly to the mysterious and difficult qualities of these paintings’ abstraction. The two paintings are very similar in overall appearance. At the time, Braque and Picasso were using the same pictorial language and had stopped signing the front of their paintings, sometimes making it difficult to distinguish authorship of individual works.

Where are the musicians?

The artists’ joint exploration of new pictorial strategies for representing solid forms in space became something quite different from their earlier investigations. There are no clear representations of recognizable solid forms in either painting, and the figures that are the subjects of the paintings seem to be absent as well. Both are intended to represent musicians: in Braque’s, a man plays a guitar, while in Picasso’s a woman plays a guitar or zither. Finding the representations of the bodies of these figures is, however, virtually impossible. Knowledge of earlier Analytic Cubist works can help direct our efforts.

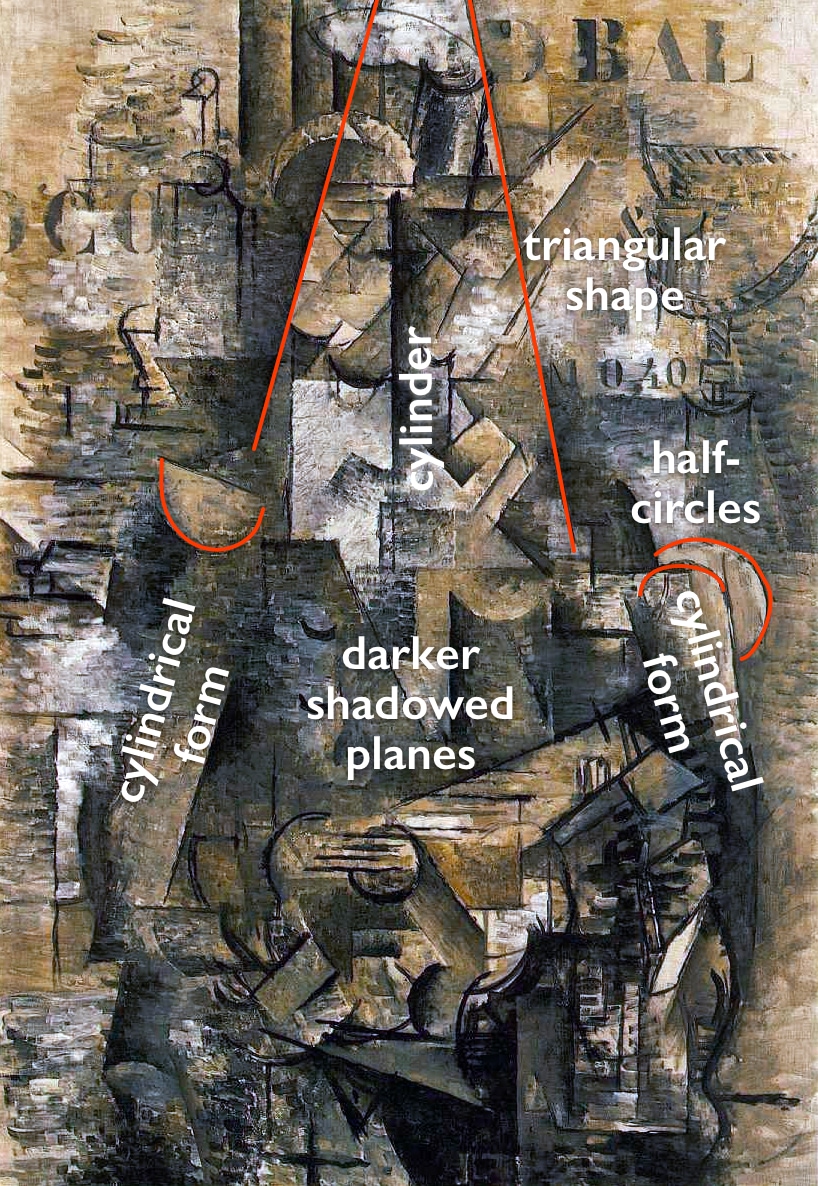

Cubist portraits and figure paintings typically follow the traditional format of placing the figure in the center of the canvas. In The Portuguese , darker shadowed planes suggest the upper body in the center. There are also suggestions of cylindrical forms representing the upper arms on the sides of this area, and half circles above them indicate shoulders. On top of the dark torso area rises a long lighter triangle outlining a collection of smaller forms surrounding another dark cylinder. This is the area of the man’s neck and head.

Looking for identifiable signs

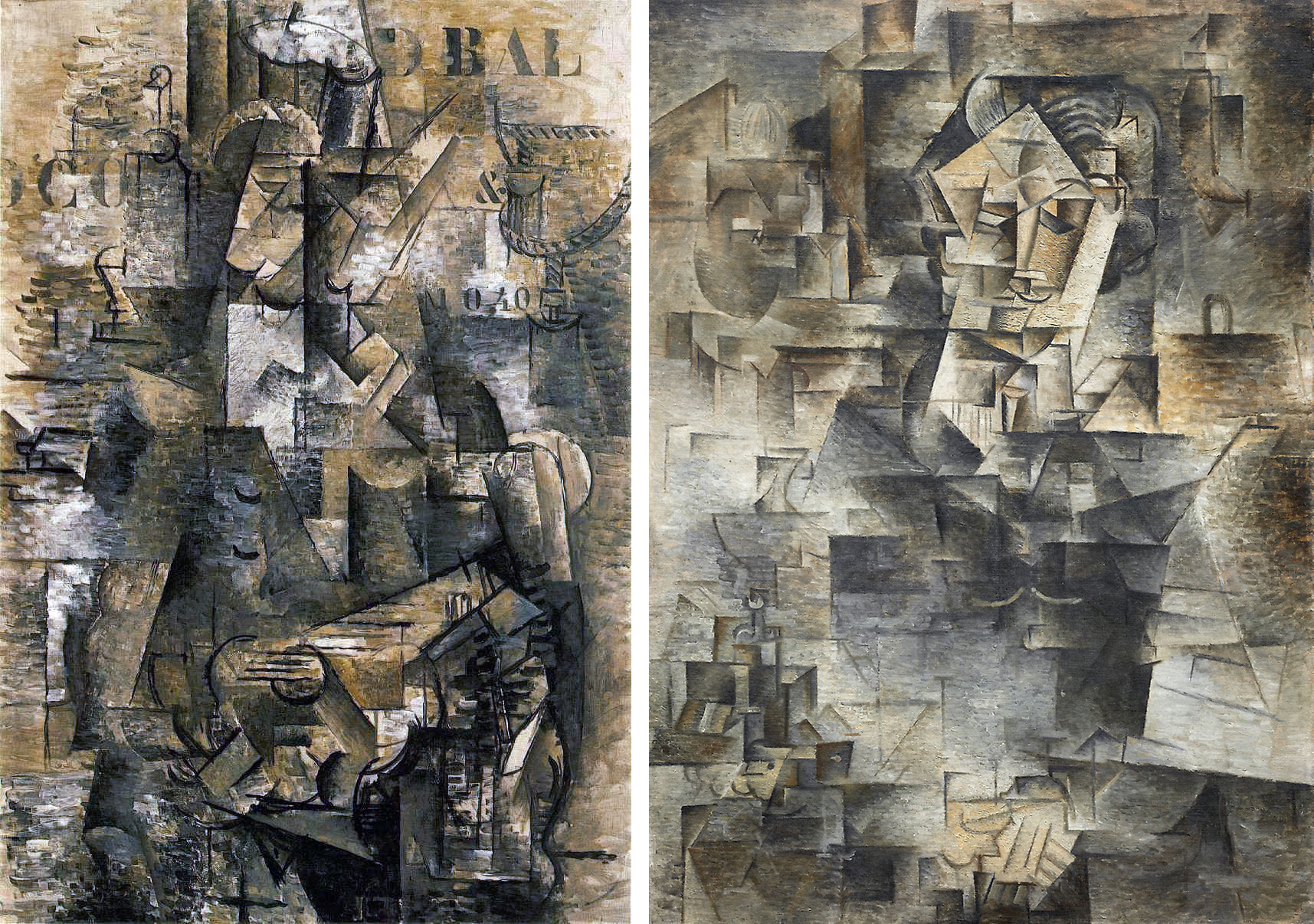

Left: Georges Braque, The Portuguese , 1911–12, oil on canvas, 46 x 32 inches (Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland) Right: Pablo Picasso, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler , 1910, oil on canvas, 39 9/16 x 26 9 / 16 inches (Art Institute of Chicago)

Picasso’s Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler uses a similar yet more legible strategy of contrasting light and dark areas to suggest the head above the body. The face of Braque’s guitar player is more abstracted than Kahnweiler’s face, in which we can find the eyes, nose, and mouth / mustache fairly easily.

In Braque’s painting, curved lines may represent closed eyelids, the bottom of the nose, a mustache, or a chin, but no clear relationships between these marks and those next to them solidly anchor our translation of the schematic lines and angles into a legible face . We cannot identify even the basic features – eyes, nose and mouth – with certainty.

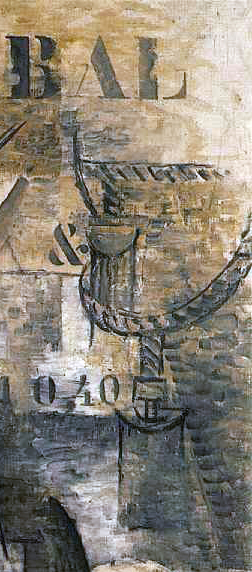

While the guitarist’s face and head in Braque’s painting are a welter of black lines and shifting light and shadowed planes, there are some legible signs within the painting. The one that is most helpful in terms of orienting the viewer is the black outline of the guitar’s sound hole crossed by black horizontal lines indicating the instrument’s strings in the center of the lower portion of the painting. A bright rectangle projects diagonally to the right from the sound hole to indicate the guitar’s fret board.

Georges Braque, The Portuguese , detail, 1911–12, oil on canvas, 46 x 32 inches ( Kunstmuseum , Basel, Switzerland)

Once we recognize the location of the guitar we can begin to look for the signs of the figure holding it. This approach to reading Cubist works by looking for identifiable signs and establishing others based on their relationship to them is key to understanding Cubist paintings, particularly the later ones.

They are structured like a language in which basic units (comparable to words) are placed in relation to each other (as words are in a sentence), making it possible to represent and communicate an infinite number of ideas. You could also think of Cubism as an attempt to create a new alphabet or sign language for representation.

A deeper understanding

Georges Braque, The Portuguese , detail, 1911-12, oil on canvas, 46 x 32 inches ( Kunstmuseum , Basel, Switzerland)

Some early theorists of Cubism, including Kahnweiler, thought the Cubist system of representation would prompt a deeper understanding of its subjects than traditional naturalistic representation. We know much more about things than the limited views that traditional representational paintings can supply. When we consider what a Cubist painting represents we engage in an intellectual or conceptual activity rather than a merely perceptual or visual one. The limited gray and brown palette enhances this intellectual approach by denying us the sensual pleasures of color.

Braque included some identifiable forms to indicate the environment surrounding the figure in The Portuguese . The most noticeable is the loop of rope in the upper right. This is a recurring motif in contemporary works by both Braque and Picasso that represents a rope and tassel curtain tie back; here it suggests the guitar player is in an interior space, possibly a cafe. This is not certain, however; the surrounding environment is often interpreted as the deck of a ship in harbor, largely because Braque informed Kahnweiler that he saw the Portuguese guitar player in that context.

Including letters, numbers and symbols

One of the most striking aspects of The Portuguese is the inclusion of letters, numbers, and an ampersand in the painting’s shadowy, abstract planes. They are in standardized stencil format and suggest partially visible posters or painted signs, perhaps on the walls or windows of an interior space. They are also flat forms floating in ambiguous relation to the complex spatial planes depicted in the painting; neither clearly foreground nor background, they remind the viewer that the painting is literally a flat surface and even its confusing shallow planar space is an illusion.

The letters, numbers, and ampersand also repeat our experience of trying to understand the painting by the limited number of identifiable visual signs. We recognize them as individual signifying units, but they don’t make up complete words; the information they provide is only partial, and we have to fill in the blanks.

The Portuguese offers an array of clues in the form of letters, symbols, abbreviated representations, suggestive forms, and signs. It is a mystery with many possible readings and no single correct solution. By the time The Portuguese was painted neither Braque nor Picasso worked directly from life. Despite Braque’s letter informing Kahnweiler that the painting’s subject was a Portuguese guitar player he saw on board a ship in Marseilles, it is unlikely that a specific real world scene is the basis for every detail in the painting.

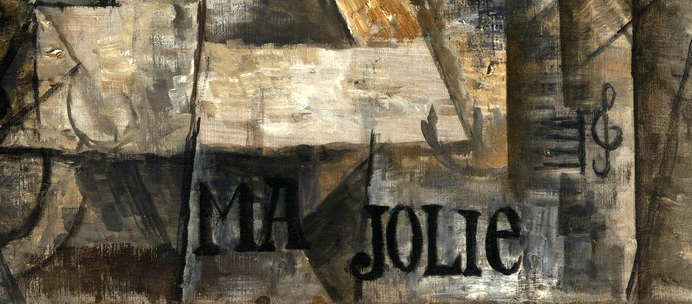

Pablo Picasso, Ma Jolie , 1911–12, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 25 3/4 inches ( MoMA )

Music as a subject

Picasso’s Ma Jolie is even more abstract than Braque’s The Portuguese . Other than a greater concentration of shaded planes in the center of the painting there is little suggestion of a distinction between figure and background, or head and body. Picasso does provide a few visual hints of the subject, signs that he used, often more legibly, in contemporary works.

Curved black lines in the lower corners are often interpreted as indicating the arms of a chair, and the group of short parallel lines ending in circles on the lower right may be tassels or fringe on the chair. Six vertical lines in the center of the painting suggest the strings of a guitar or zither. The words “Ma Jolie” (“my pretty one” in French) accompanied by a musical staff and treble clef painted at the bottom of the canvas refer to a popular song of the day, as well as to Picasso’s nickname for his current girlfriend.

Pablo Picasso, Ma Jolie , detail, 1911–12, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 25 3/4 inches ( MoMA )

The reference to a popular song adds to the multiple ways music is the subject of Analytic Cubist paintings. In part, musical references are practical; musical instruments are more complex and interesting forms than the glassware and bottles that were also common Cubist subjects. Musical instruments are easy to identify by parts and lend themselves to the formal transformations foundational to Cubist innovations. Braque was an amateur musician, and both artists had various instruments in their studios. Music was also an important touchstone for Cubism more generally. As a non-representational art form with its own internal structures and systems of tones and rhythm, music is an abstract language that is suggestive rather than concretely referential. The paintings of late Analytic Cubism with their mysterious objects and figures in indeterminate space are like music; they are visual orchestrations of painted forms in which shifting patterns suggest far more than they clearly depict. For both Picasso and Braque these paintings were as close as they were willing to approach complete abstraction.