Primitivism in art involves the appreciation and imitation of cultural products and practices perceived to be “primitive,” or at an earlier stage of a supposed common scale of human development. This definition contains a basic contradiction: the primitive is admired and even seen as a model, but at the same it is also presumed to be inferior, because it is not fully developed. This paradox makes primitivism a concept that is both intellectually and morally complex.

Primitivism in a broad historical context

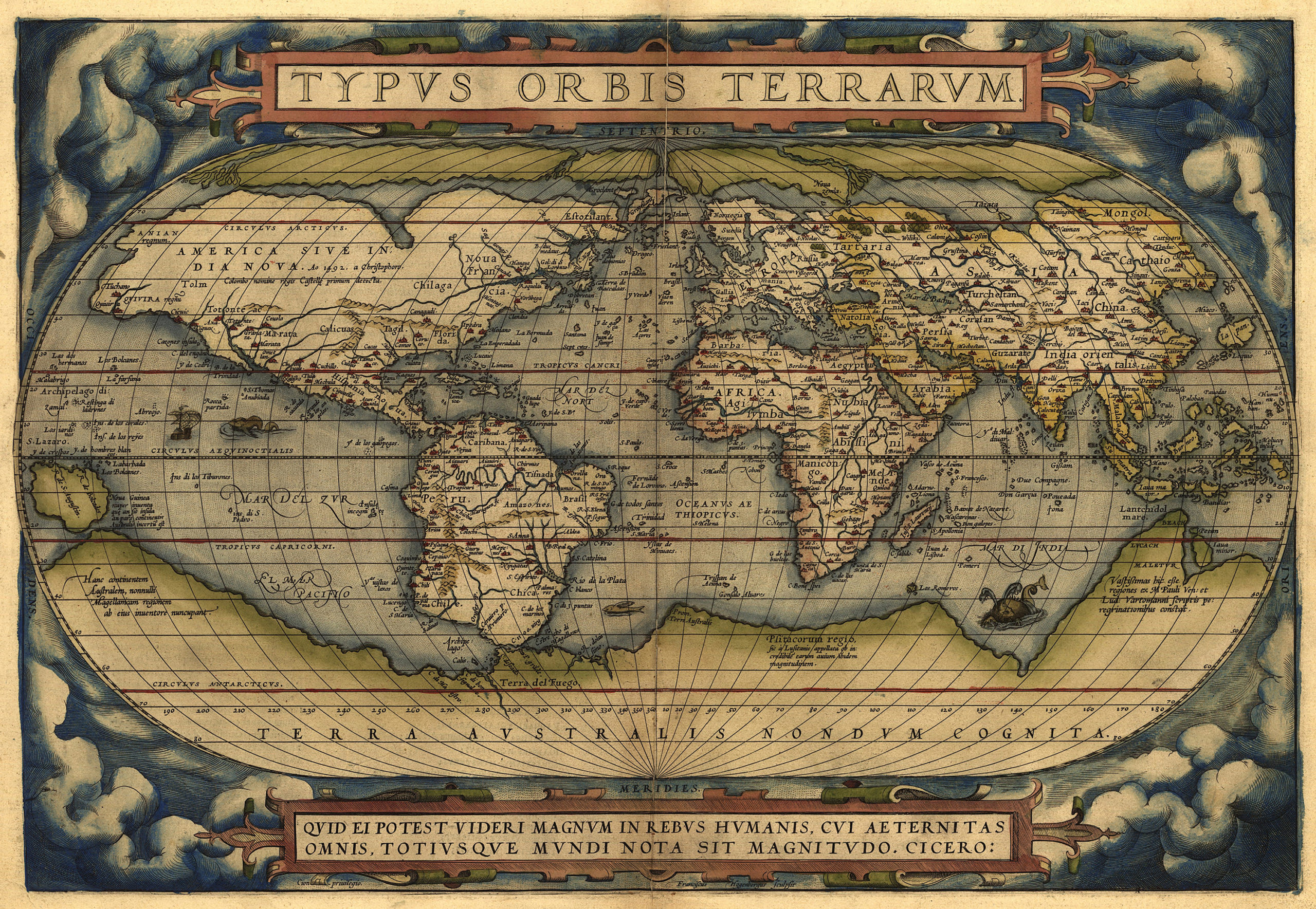

Primitivism was fostered during the modern period by two phenomena. First, the so-called Age of Discovery from the 15th through the 17th century brought Europeans into close contact with a wide array of previously unknown cultures from Asia, Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. As a result of the military and technological advantages of the West, the new social and economic relationships established with these cultures were often exploitative, including theft of raw materials, enslavement, and colonial rule.

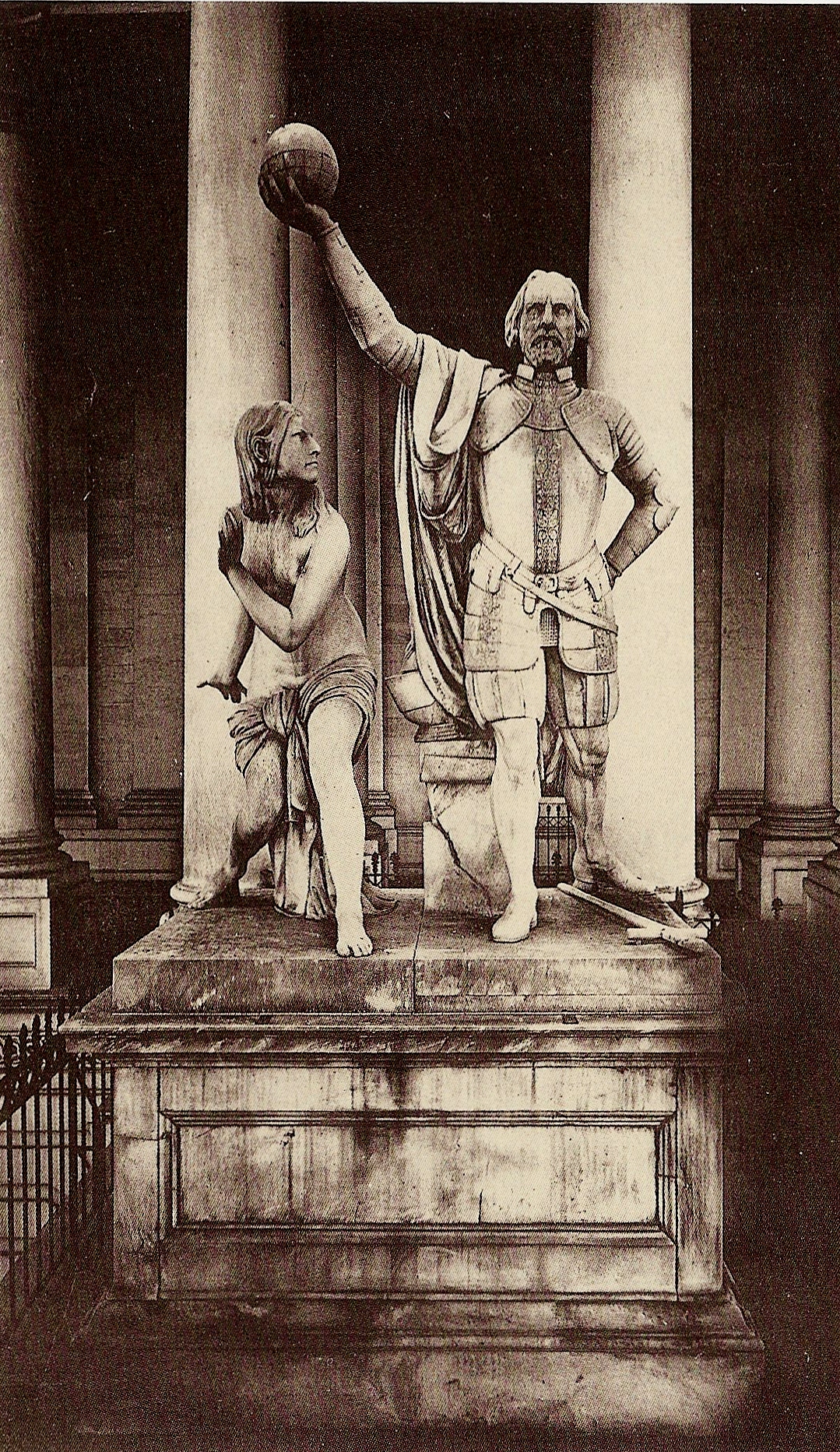

The body language in Luigi Persico’s Discovery of America exemplifies such relationships. The male European “discoverer” stands dominant, dressed in Renaissance-style metal armor and carrying a sphere that simultaneously represents the globe he has conquered and the “enlightenment” he brings, while the nearly-naked indigenous woman cringes, awestruck and submissive, by his side.

Second, primitivist attitudes were fostered by anxieties caused by the rapid social, economic, and political changes that accompanied the scientific and industrial revolutions of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

Philip de Loutherbourg, Iron Works, Coalbrookdale, lithograph from Picturesque Scenery of England and Wales, 1805, 31 x 38.7 cm

Within a few hundred years, cultural patterns based on religion and agriculture that had lasted for millennia were upended. Science was displacing faith, and machines were replacing human labor or creating lower-paying, unskilled jobs. Increasing numbers of people lived in cities rather than in villages and worked in factories rather than on farms. Primitivism was a sort of antidote to modernity itself, a nostalgia for an imagined “state of nature” when humankind is assumed to have lived more instinctually and in closer harmony with the natural and spiritual worlds.

The “noble savage”

One of the defining concepts of primitivism is that of the “noble savage,” an oxymoronic phrase often attributed to the eighteenth-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, although he never used it. Now recognized as a stereotype, the noble savage is a stock character of literature and the arts who may lack education, technology, and cultural refinement, but who lives according to universal natural law and so is inherently moral and good. Many popular books and films exemplify the concept of the noble savage, including Tarzan, The Gods Must Be Crazy, Dances With Wolves, and Avatar.

In Avatar, for example, the indigenous, blue-skinned Na’vi are technologically inferior to the humans who come to mine their Eden-like world for resources, but they are morally superior and closer to nature. Although the Na’vi are loosely based on Native Americans, it is important to remember that the primitivist concept of the noble savage is essentially mythic, not documentary.

Tropical paradise

The late-nineteenth century French artist Paul Gauguin created some of the most enduring and influential images of the noble savage. Decrying the corruption of “putrified” Europe, Gauguin left France in 1891 for the South Pacific island of Tahiti, where,

under an eternally summer sky, on a marvelously fertile soil…the…happy inhabitants of the unknown paradise of Oceania know only the sweetness of life.Paul Gauguin, letter to J. F. Willumsen, Pont-Aven, 1890, as translated in Herschel B. Chipp, Theories of Modern Art (London, 1968), p. 79.

Although aspects of Gauguin’s paintings of Tahitian life have some basis in reality, they combine multiple cultural traditions, including South Asian and Egyptian as well as Oceanic. They are also carefully selected to reinforce pre-existing European stereotypes of a tropical paradise replete with colorful plants, succulent fruits, and quaint superstitions.

Gauguin’s paradise is populated largely with young, semi-nude women, promoting fantasies of sexual freedom as well as perpetuating a long-standing European convention that associated women with nature. The model for The Seed of the Areoi was a thirteen-year-old Tahitian girl who was soon to be pregnant with Gauguin’s child. For many people today, Gauguin’s exploitative relationship with the Tahitians outweighs the admiration he professed to be expressing, and perhaps even his artistic legacy.

Gaucherie and sincerity

Gauguin’s primitivism extends to his style as well as his subject matter. He did not wish to represent “the primitive” second-hand, he aspired to live it and embody it. Notice the stiffness of the girl’s pose, the reduction of her anatomy to basic geometric shapes, and the near-total absence of chiaroscuro or cast shadows.

Along with an appreciation for “primitive’” subject matter, many modern artists also cultivated a style that they saw as primitive. Prototypes of this style were found in children’s art, folk art, and pre-Renaissance art as well as non-Western art. Gaucherie — awkwardness — was seen as a mark of sincerity and striving, which was preferable to the shallow facility of Academic art.

In addition, the naturalistic style taught in the Academic system was seen as being suited only to representing the surface appearances of material objects. Artists in search of alternatives to naturalism saw in primitive art and folk art a truly natural way to draw: one available without training, and one that is responsive to the richness of human subjective life: concepts, emotions, and spirituality, rather than a mere record of perceptions.

Henri Rousseau, The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope, 1905, oil on canvas, 200 x 301 cm (Fondation Beyeler, Basel)

Similar stylistic qualities are seen in French customs-inspector-turned-artist Henri Rousseau’s The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope. Rousseau lived most of his life in Paris, and his experience with primeval tropical environments was limited to trips to the zoo and botanical garden. However, his self-taught, naïve painting style meant he was widely admired as a modern primitive.

Cultural appropriation?

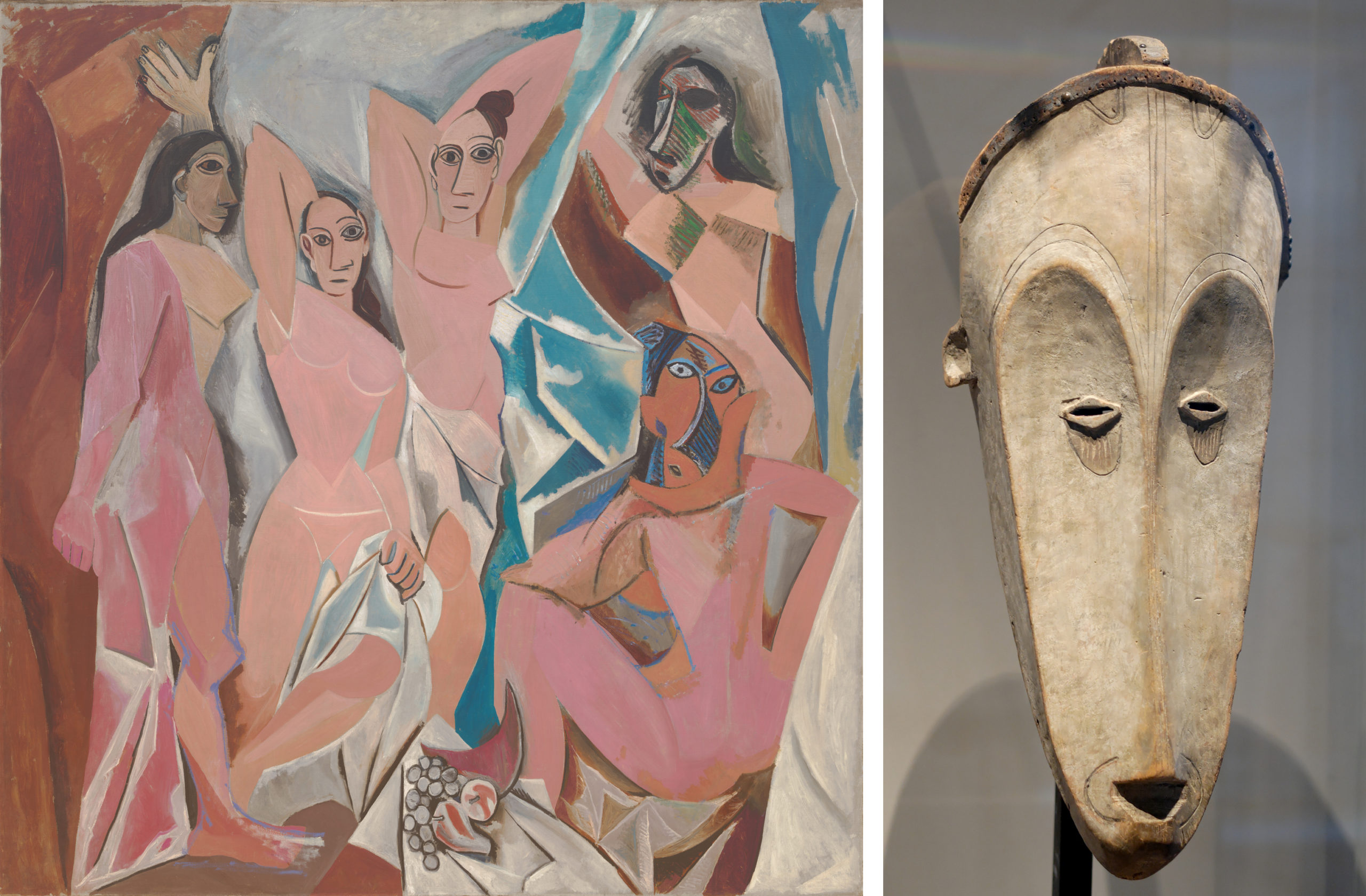

In 1907, a famous cross-cultural artistic encounter took place when Picasso went to see the African masks exhibited at Paris’s Trocadero Museum of Ethnology. Shortly thereafter, he revised the ambitious painting of prostitutes that he was working on to include mask-like faces on the two rightmost figures. Thus began a two-year engagement with African art that contributed to the invention of Cubism.

Left: Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907 (MoMA); Right: Fang mask, Gabon, 19th century (Musée du Louvre)

In the end, Cubism became very different from African art, but Picasso’s borrowings have raised concerns about cultural appropriation that are endemic to much primitivism. It is almost impossible to avoid consuming or using elements of other peoples’ cultures — blue jeans, paper, and pizza were all invented by and specific to one particular culture at one time. The charge of “cultural appropriation” is generally only leveled when a member of a dominant culture gains money or cultural capital by appropriating artifacts of a non-dominant culture. The vast commercial success of white, blues-based rock-and-roll musicians when their black progenitors lived in relative poverty is a good example.

It is hard to determine exactly how much of Picasso’s success is due to his cross-cultural borrowings, but certainly his enormous reputation and the astronomical prices commanded by his works at auction form a poignant contrast to the often literal anonymity of the mask-makers from Africa whose works helped inspire his artistic innovations.

Primitivism and industrialization

The German Expressionists were another group of artists who found inspiration in African art. Like Gauguin, they were motivated by an antipathy toward industrialization and the social and economic changes that it entailed, especially what they saw as a vain, shallow, and exploitative middle class.

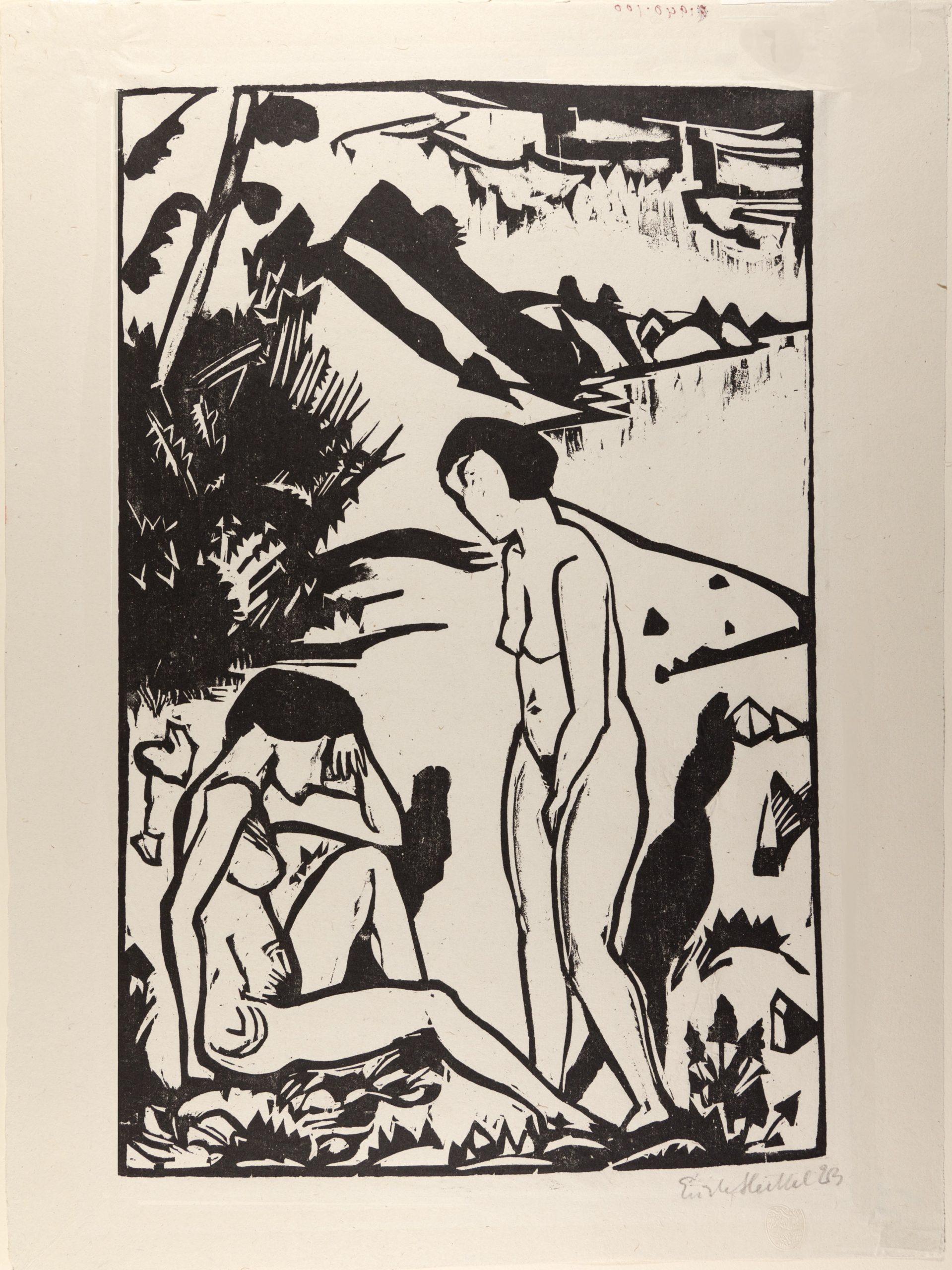

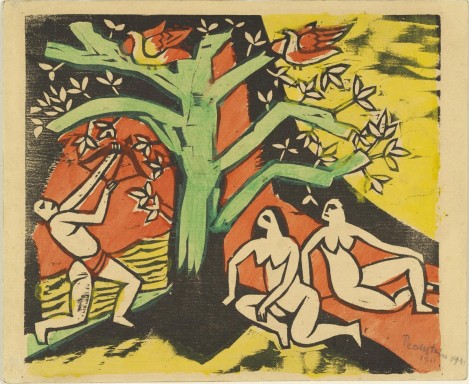

They found an antidote to modernity in a retreat to a pre-modern state of nature, as embodied in Erich Heckel’s print of two women bathing in a mountain landscape. The women’s nudity is a paradoxical mixture of eroticism and innocence. It combines the purity of humankind in Eden, when the body was not seen as sinful, with the presumed liberated sexuality of primitive people, which is denied to members of modern bourgeois society.

The intentional gaucherie (awkwardness) of Heckel’s style, another aspect of the work’s primitivism, is enhanced by the work’s medium. Woodcut was an old-fashioned technique of printmaking, but it was revived by the German Expressionists in part because of the natural materials it used and the crude simplicity of the images it tended to produce. It was markedly different from more recent and higher-tech printmaking processes such as etching, lithography, and photography.

Primitivism and colonialism

It is no coincidence that primitivist art was created and consumed by Western nations that were at the same time practicing colonialism: occupying and plundering much of Africa, Asia, and the Americas for labor and resources.

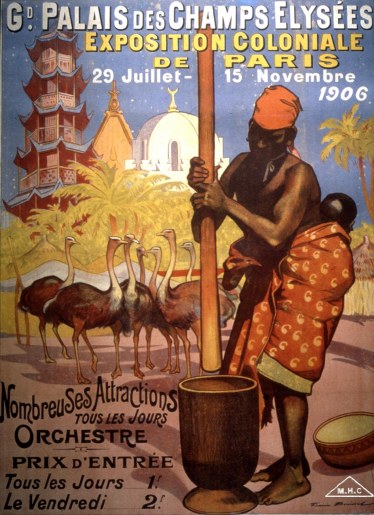

European fascination with these cultures was reflected in dozens of “colonial” exhibitions during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century. These often included what were essentially human zoos in which ethnic “specimens” would enact their cultural practices for curious spectators. The background of this poster for the 1906 Colonial Exhibition in Paris includes a pagoda, a North African mosque, and a Cambodian temple to display the widespread colonial holdings of France at the time. The foreground shows a living diorama of an African village, complete with mud and straw huts, ostriches, and a semi-nude woman with a child grinding grain against a backdrop of palm trees.

Although the work’s naturalistic style and depiction of labor are notably different from the artworks we have been examining, this exhibition poster singles out many of the same primitivist qualities lauded by modernist artists. These qualities seem designed to exemplify how much more “advanced” European culture is. The mud huts would have formed a stark contrast to the vast, modern iron-frame architecture of the Grand Palais in Paris, on the grounds of which the colonial exhibition was held. The woman’s task, grinding grain, was doubtless chosen in part to demonstrate her people’s capacity for hard physical labor. This was, however, also one of the first forms of industrialized labor in the West, where mills driven by wind and water power replaced hand grinding.

The poster thus shows the very primitive state of technology in this woman’s culture. Her semi-nudity also contrasts with the elaborate costumes worn by contemporary Parisian women, and would have promised a titillating attraction for the Belle Epoque visitors to the exhibition.

Even when these qualities are re-framed as positives — as antidotes to modern ailments such as overcrowded cities, runaway technology, emotional and sexual repression, and the loss of spirituality and of connection with nature — the stereotypes of primitivism are still problematic. Framing other cultures as “primitive” ultimately suggests the need for external aid and guidance, and thus helps to justify Western colonial practices. Primitivism is a peculiar mixture of admiration and denigration, appreciation and exploitation, elevation and repression. This is the paradox at the heart of the concept of primitivism; a paradox evident ever since the invention of the phrase “noble savage.”