Femininity and masquerade

In Arndt’s Self-Portrait with Veil, we see a woman with tightly pursed lips staring straight ahead with a doll-like expression. Layers of lace and fringe cover her upper body and lace veils her face. Her head is crowned with abundant flowers. Without knowing that the picture was taken in 1930, we might assume that it belonged to a less modern era because of the antiquated details she presents.

Why would quintessentially modern “New Woman” Gertrud Arndt represent herself as trapped in the layers of ultra-feminine attire reminiscent of traditional folk costume?

This portrait is part of a series of 43 staged self-portraits Arndt called Maskenporträts (Masked Portraits). Arndt took her Self-Portrait with Veil by shooting into the bathroom mirror. The “drag bag” that she used for her costuming in these photos contained veils, hats, bits of lace, paper flowers, and other fancy, feminine—but outmoded—accessories. Layers of lace, floral patterns, and feathers—various competing textures for connotations of femininity—cover every area of the portrait. The artist may have taken some inspiration from traditional folk dress from her birthplace in a border region now part of Poland.

In the photographs from this series, Arndt tacitly refers to Joan Riviere’s 1929 psychoanalytical essay “Womanliness as Masquerade,” which suggested that women use their femininity as a form of Masquerade—or “drag”—to make themselves seem less threatening in the face of anticipated retribution from men when women dare to seek power or respect in a patriarchal society. [1]

Arndt’s layers and textures almost merge the figure and the background, wedding the subject to these gendered accessories. The textiles suffocate her, domesticize her, and mark her as someone subsumed by traditional gender roles that indicated that women should be confined to the home. The veil, the flowers, and the feathers hide her short, bobbed “New Woman” haircut. Arndt’s choice to pose herself among so many textures, clothes, and props in Self-Portrait with Veil suggests she was well aware of the power of photography to interrogate gender roles. She created an ironic image of herself as an old fashioned woman, blandly merging with her dated, over-decorative interior (even though her actual house interior was strikingly modern).

Gertrud Arndt, Self-Portrait, 1926 (Bauhaus Archive)

In a very different self-portrait she made at her studio in 1926, Arndt styled herself in short sleeves and a knee-length skirt with her short-bobbed hairstyle (all modern stylistic departures from the corseted hour-glass figures and elaborate upswept long hair-dos of the prior era). Self-Portrait with Veil, made just four years later, provides a stark contrast with Arndt’s 1926, Self-Portrait.

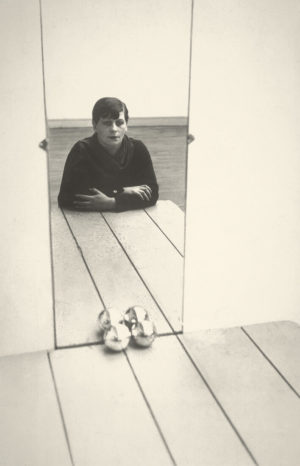

Self-Portrait with Veil also contrasts with images of the New Woman who are shown outdoors, with cars, dressed in knee-length, loose-fitting dresses, and cloche hats. Arndt’s departure from the commonly seen image of the “New Woman” is clear if we compare her Self-Portrait with Veil to Florence Henri’s Self-Portrait. Henri, like Arndt, was a woman photographer at the Bauhaus, a prominent modernist institution. Her portrait was made one year earlier than Arndt’s veiled portrait. While Arndt’s self-portrait displays a masquerade of femininity, Henri’s focuses on the gender-boundary-questioning that was typical of the “New Woman.”

In Self-Portrait, Henri has negated nearly all visible signifiers for femininity—except her use of lipstick and eyeshadow—and even added a pair of reflective “balls” to reinforce her point. Henri’s experimental framing, strong diagonal lines, and hard-edged modernism echo the work of László Moholy-Nagy who taught at the Bauhaus. While just one year later, Arndt seems aligned with the Bauhaus Photography Master (teacher) Walter Peterhans in his concern for soft textures and layering.

Walter Peterhans, Portrait of the Beloved, 1929, gelatin silver print, 28.3 × 25.7 cm (Smart Museum of Art, Chicago)

For Gertrud Arndt, taking photographs of herself in various costumes and accessories while playing roles became a private form of entertainment, and reflected the common use of photography at the Bauhaus. Arndt was an enrolled student at the Bauhaus from 1923–1927, and after she graduated and was living in Bauhaus faculty housing with her instructor husband, she was a guest student in the Photography workshop from 1929–1932. Arndt’s Masked Portraits preceded Cindy Sherman’s well-known Untitled Film Still self-portrait series by almost 50 years, but provided a clear precedent for the examination of traditional gender roles using photography.

With her heavy-lidded, faraway gaze and her prim pursed lips, in 1930 Gertrud Arndt was living in the middle of a mature Modernist project in which, as a woman, she could not participate as much as she once hoped. She could not study architecture at the Bauhaus, and she was placed in the Weaving workshop (with most other Bauhaus women) while she was a student. While she turned her back on textile production, in her self-portrait she buries herself in layers of textiles and accessories coded as “feminine” to make an ironic point about the too often stifling position for women at the Bauhaus. The youthful hope embedded in her 1926 “New Woman” self-portrait from her student days had only four years later drowned in a costumed image of an old doll, when she was only 27.