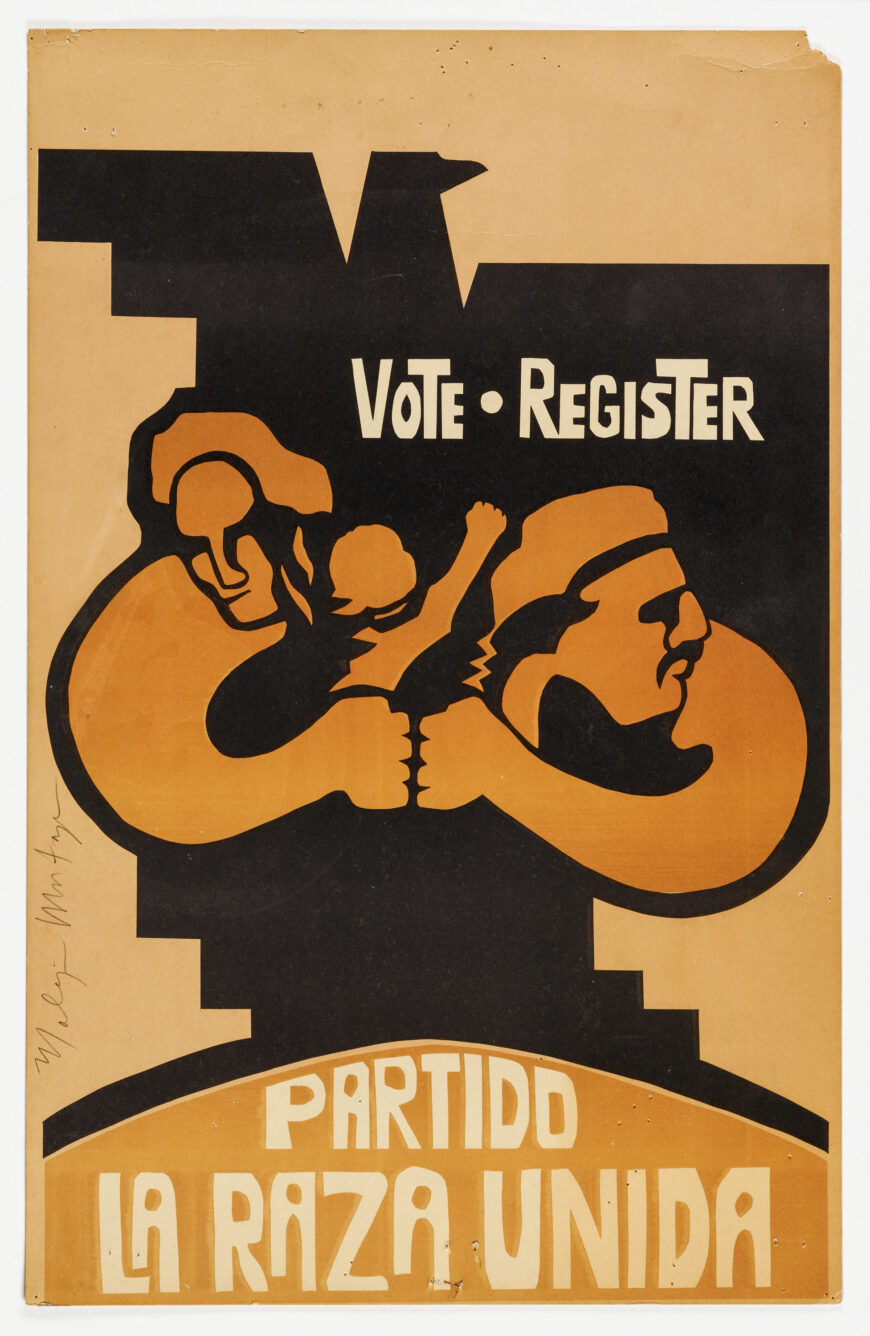

Malaquías Montoya, Vote Register, c. 1971, screenprint, 54 x 34.3 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.) © Malaquías Montoya

We are all familiar with graphic propaganda, from James Montgomery Flagg’s iconic image of Uncle Sam to Shepard Fairey’s rendering of Obama in Hope. These posters directly address the viewer, exhorting action: to vote, to join the armed forces or, in the case of advertisements, to buy. This impulse to provoke action and change was central to the art of the Chicano movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Rather than aspiring only to create beautiful aesthetic objects (which they certainly did), artists working with and alongside this civil rights movement placed their art directly in the service of social change.

While the Chicano movement is most frequently understood as a social movement, it was also a cultural movement. Painters, musicians, actors, photographers, and writers not only promoted specific causes or organizations, they also endeavored to develop a new visual language to express and visualize Chicano identity, self-determination, and political consciousness.

Raza Unida Party (RUP)

Malaquías Montoya’s Vote Register was created in this spirit and with a specific cause in mind: the growth and political power of the Raza Unida Party (RUP). This Chicano-led party originated in Texas and achieved historical gains there; RUP candidates swept municipal elections in Crystal City, Texas, inspiring optimism about the possibility of a third political party that would be more responsive to Chicano needs and concerns. The party’s platform and focus varied by region, although Chicano self-determination remained its unifying principle. After making inroads in Colorado, activists began opening chapters across California. By early 1971, there would be at least 14 chapters across the state. While some hoped the RUP would produce meaningful electoral victories, others saw it as a mechanism to make the Democratic Party more responsive to Chicanos. While the RUP never achieved a permanent foothold in California, campaigns in Los Angeles and elsewhere proved disruptive to the election campaigns of Democratic candidates.

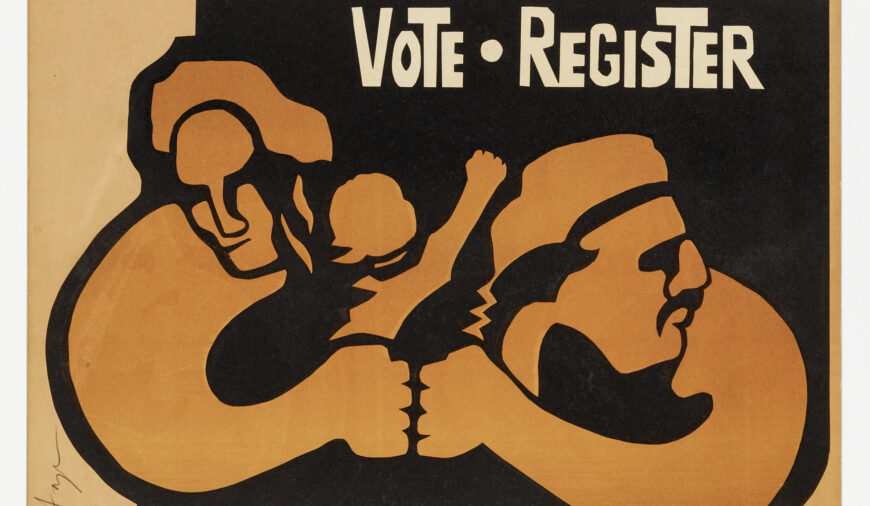

Eagle and family (detail), Malaquías Montoya, Vote Register, c. 1971, screenprint, 54 x 34.3 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.) © Malaquías Montoya

Montoya’s silkscreen is obvious in its address to viewers: register and vote. Of course, the immediate goal was to generate support for and interest in the RUP. But depending on the party chapter, Chicano voter registration was either a desired byproduct or a primary goal of RUP organizing. While tied to the RUP, the poster also carried a more general message about the importance of voting. But the poster also visually conveys the notion of a “united race.” The figures are framed by a dynamic rendition of the United Farm Workers’ eagle, a symbol that was used across posters, flags, flyers, and other material associated with the union and its public outreach in the 1960s and 1970s. The highly visible campaigns of the UFW—including an international grape boycott—had galvanized Chicanos across the country by the mid-1960s. Their eagle symbol then became one of the most identifiable visual icons of the broader Chicano movement, making its way onto posters, t-shirts, flags, and protest signs. And the figures themselves—a man, woman, and child (with a raised fist)—are representative of the heteronormative “Chicano family” writ large, a common trope within movement-era art. The father here is also wearing a beret, a clear reference to the Brown Berets, a social justice organization established in Los Angeles and modeled in part on the Black Panthers. In this formulation, La Raza Unida promises to unite the entire “family,” from rural farmworkers to urban activists fighting against police brutality, educational inequality, and the Vietnam War.

The silkscreen and political art

Montoya was originally approached by activists in Oakland to create this poster, but the image circulated beyond the Bay Area. Montoya was periodically asked to make new versions or to repurpose his original design for different uses. He helped produce bumper stickers for the RUP, for instance, based on this original design. And when Raul Ruiz, editor of La Raza magazine, ran as an RUP candidate in Los Angeles, Montoya’s image adorned the cover of an issue dedicated to his campaign and the party’s efforts. This was a primary benefit of producing silkscreen posters—they are easily reproduced and allowed a message or image to be distributed widely.

While the political purposes of the poster might be apparent, it also represented a challenge to entrenched notions of “fine art.” The very premise of the silkscreen poster, in fact, defied the logic inherent to the art world at the time. Mid-century art was nearly synonymous with Abstract Expressionism, a painting movement centered largely in New York. Despite being closely associated with a cadre of white painters (like Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman), critics imagined Abstract Expressionism to be a “universal” form of expression. What’s more, its primary value resided in its ability to offer the viewer a supposedly transcendent aesthetic experience divorced from everyday concerns. It was a form of art premised on separating life from art and rejected the Social Realism of the previous generation of artists.

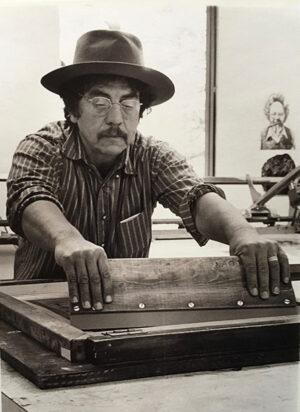

Montoya in the screen printing room at California College of Arts and Crafts, early 1980s (courtesy of the artist)

Chicano art aspired to be the antithesis of this philosophy in every respect, and silkscreen posters were central to this goal. They were one facet of a political and artistic movement that prioritized making art accessible. To begin with, the materials required to create these posters were relatively minimal and inexpensive: paper, ink, and screen printing equipment. This placed art within reach of almost anyone with the desire to create. These materials (and the training required to use them) were available at grassroots cultural centers that emerged as an extension of the Chicano movement, removing barriers to art education. Second, these posters were not precious, isolated objects of art intended for aesthetic contemplation; they were meant to circulate, to be posted on the streets, to adorn bedroom walls and college campuses. Some were even pasted to placards and used in protests. Art proliferated throughout Chicano neighborhoods rather than being confined to museums. As Montoya has noted about his own attraction to the medium: “Posters were a good way to reach the community; it was like a giant visual newspaper.” [1] Far from shying away from representational forms or politics, posters were often created to promote a certain cause, a political stance, or even an event. The Chicano poster was art integrated into life rather than separated from it.

Politically committed artists like Montoya who worked alongside the movement—many in collaborative or collective situations—often held no aspirations or illusions of making their way into museums or being accepted into the art world. He and others understood their work as an extension of the Chicano movement, a tool to be used in the service of social justice and political change. The way this image circulated widely, and as a key part of a political movement, epitomized the general philosophy of Chicano movement art.

Montoya’s philosophy and teaching

In 1980, Montoya and his wife Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya formalized this philosophy in an essay titled “A Critical Perspective on the State of Chicano Art.” Responding to the increasing institutionalization of Chicano art, they advocated for a politically committed art that remained accessible to the people. Art confined within the walls of the museum or the homes of elite collectors, in their estimation, was contrary to the foundational logic of Chicano art. And for Chicano artists, they argued, social justice and community should take priority over personal expression or financial gain. For them, the purpose of Chicano art was not to gain acceptance, entry into the mainstream, or art world validation. Beyond his visual artwork, Montoya has embodied this philosophy by teaching art in Ethnic Studies and Chicano Studies departments, themselves a direct product of the Chicano movement. While working for academic institutions, including UC Davis and UC Berkeley, the bedrock of his pedagogy was a workshop (taller) format where dialogue and community engagement were paramount. His work as an influential instructor and mentor parallels the impetus of the silkscreen poster itself: accessibility, social change, and a dedication to spreading art beyond the walls of museums and halls of academia.

This essay is part of Smarthistory’s Latinx Futures project and was made possible thanks to support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.