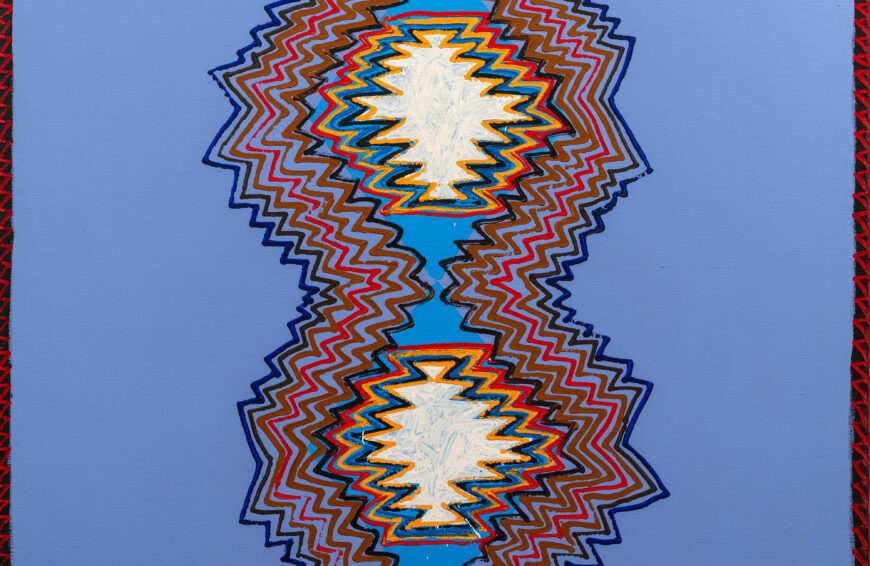

White, red, and aqua panels create an entire universe of space, absence, and form.

Conrad Marca-Relli, Cristobal, 1962, painted vinyl collage, 189.9 x 162.6 cm (Art Bridges) © Archivio Marca-Relli, Parma. Speakers: Bill Conger, Chief Curator, Peoria Riverfront Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker, Smarthistory