First International Dada Fair, Galerie Otto Burchard, Berlin, 1920 (Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin)

A sign reading “Dada ist politisch” (Dada is political) is visible on the right side of this photo of the opening of the 1920 First International Dada Fair in Berlin. The German Dadaists’ explicit engagement with politics marks a notable change from Zurich Dada, which, while iconoclastic, was rarely overtly political. This is partly because Switzerland was neutral during World War I, and provided something of an escape for the artists who gathered there. The founder of Zurich Dada, Hugo Ball, once described Switzerland as “a birdcage, surrounded by roaring lions.”[1] When Dada spread to Germany following the end of World War I, it entered the lion’s den.

Social and economic crisis

Germany was in social, political, and economic chaos after the war. Its industrial base had been decimated, and there was a struggle for political power between the right-wing Social Democrats and the left-wing Communist Party. The Spartacist Uprising, a general strike and armed insurrection by the Communists in 1919, was met with brutal repression and the extra-judicial killing of its leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Following the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1919, a new government known as the Weimar Republic was formed by the Social Democrats. The new government was immediately beset by economic difficulties that included massive war debts and the punitive reparations set by the Treaty of Versailles. To pay off its debts the government simply printed more money, which led to hyperinflation. By the end of 1922, a loaf of bread cost 200 billion Deutschmarks. Most of the German Dadaists were sympathetic to the Communist party and strongly critical of the Weimar government and its policies.

Against bourgeois capitalism

George Grosz, whose painting A Winter’s Tale (1917) is visible hanging above the “Dada ist politisch” sign, was born Georg Groß, but changed the spelling to “de-Germanize” his name as a protest against German nationalism. He was arrested during the Spartacist Uprising, and was a member of the Communist Party until 1923.

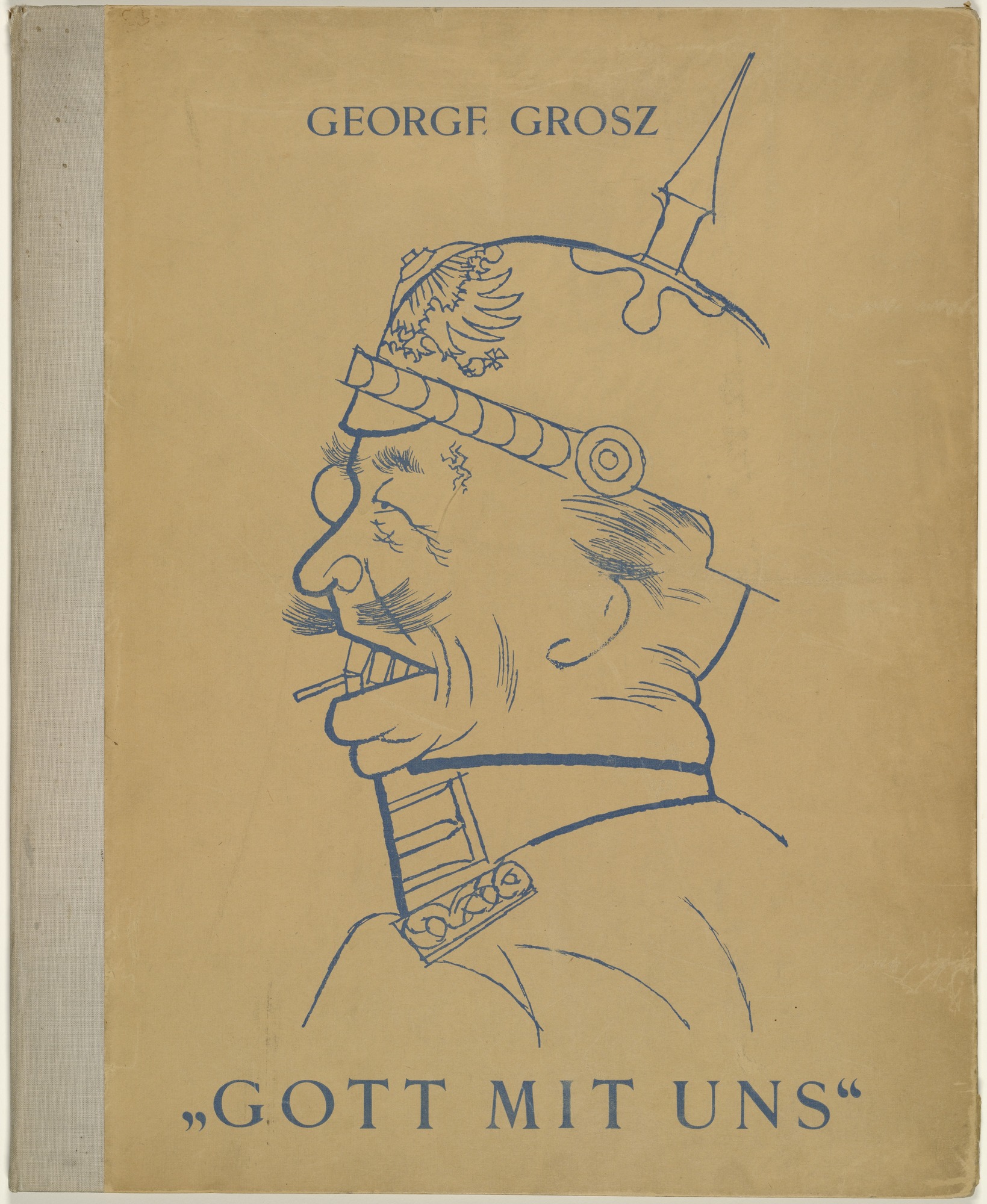

George Grosz, Cover, Gott mit uns (God with us), 1919, letterpress and line block, 49.2 x 40 cm (MoMA)

A portfolio of Grosz’s iconoclastic prints was on sale at the Dada Fair. The title “Gott mit uns” (God is with us), taken from the official slogan inscribed on the belt buckles of German army troops, is clearly mocked by the grotesque caricatures of soldiers and officers in the portfolio. Grosz and his publisher were fined for defamation of the military, and all unsold copies of the portfolio were destroyed.

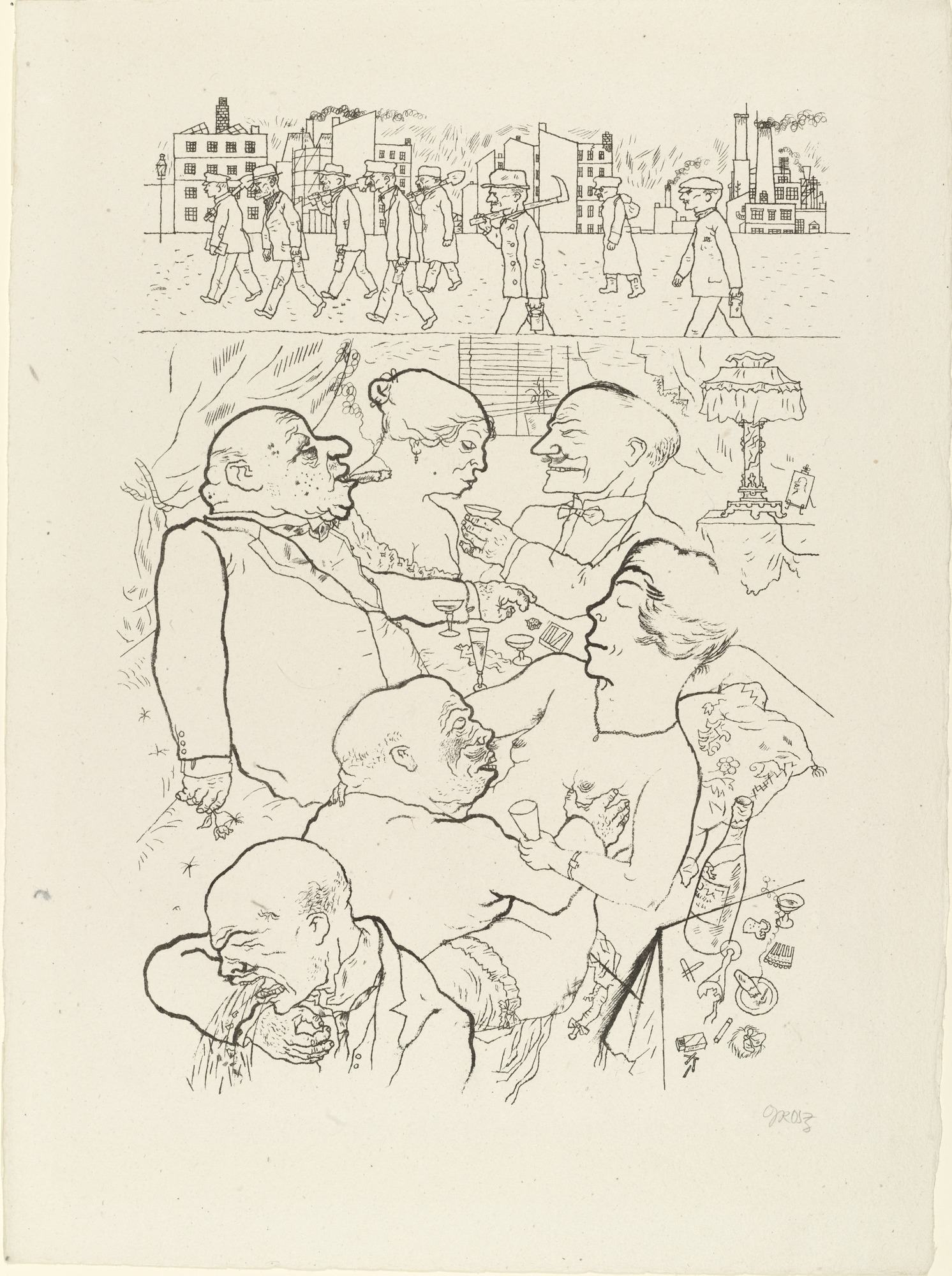

George Grosz, Dawn (Früh um 5 Uhr!), 1920/21, photolithograph from a portfolio of ten lithographs In the Shadows (1921), 48 x 35.4 cm (MoMA)

Unrepentant, Grosz continued to make prints critical of the ruling classes. His photo-lithograph Dawn shows two simultaneous early morning scenes. On top, members of the working class, tools and lunch pails in hand, trudge to work at the factory, while in the scene below, the wealthy continue to enjoy their previous evening’s debauchery. The workers are mostly thin and ragged, while the wealthy bourgeois men are caricatured as fat and dissipated figures clutching their cocktails and prostitutes.

War technologies

Another major target of Dada scorn was science and technology; this was part of a broad strategy to discredit rational thought and utopian projects. The Dada mistrust of technology also had roots in its destructive use during World War I.

A British Mark IV (Male) tank during the Battle of Cambrai, France, November-December 1917 (Imperial War Museums)

The Great War, as it it was then known, was largely fought by armies hunkered down in vast networks of defensive trenches. Offensive sorties resulted in massive casualties, as charges were met by a hail of bullets from recently-invented machine guns. Armored vehicles were invented to protect troops during charges, and continuous “caterpillar” tracks on a rhomboid frame helped these early tanks navigate the deeply entrenched terrain. Chemical weapons delivered by artillery, such as chlorine gas and mustard gas, were also brutally effective against massed troops, necessitating the use of gas masks and protective clothing. War photographs suggest not only the destructiveness, but also the dehumanizing effect of these new military technologies.

British soldiers with a Vickers machine gun wearing PH-type anti-gas helmets during the Battle of the Somme, July 1916 (Imperial War Museums)

The Communist-influenced Dadaists saw the roots of this destruction not just in the technology itself, but in what later became known as the “Military-Industrial Complex,” the factory owners and financiers who profited from weapons manufacture. In her collage Hochfinanz (High Finance), Hannah Höch shows two middle-class figures with outsized heads dominating an aerial view of Wroclaw, Prussia (now in Poland). Surrounding them are images of weaponry, machinery, and mass production: two shotguns, a factory, piston rods, a threaded bolt, the red-white-and-black Imperial German flag, and a military truck driving along a rubber tire. One of the two figures is British scientist Sir John Herschel (perhaps in reference to the contribution of scientists to the invention of war technologies), but the title High Finance suggests that the two well-dressed old men are bankers implicated in both the destructive war technologies and the exploitative practices of early-twentieth century capitalism.

War casualties

First International Dada Fair, Galerie Otto Burchard, Berlin, 1920 (Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin)

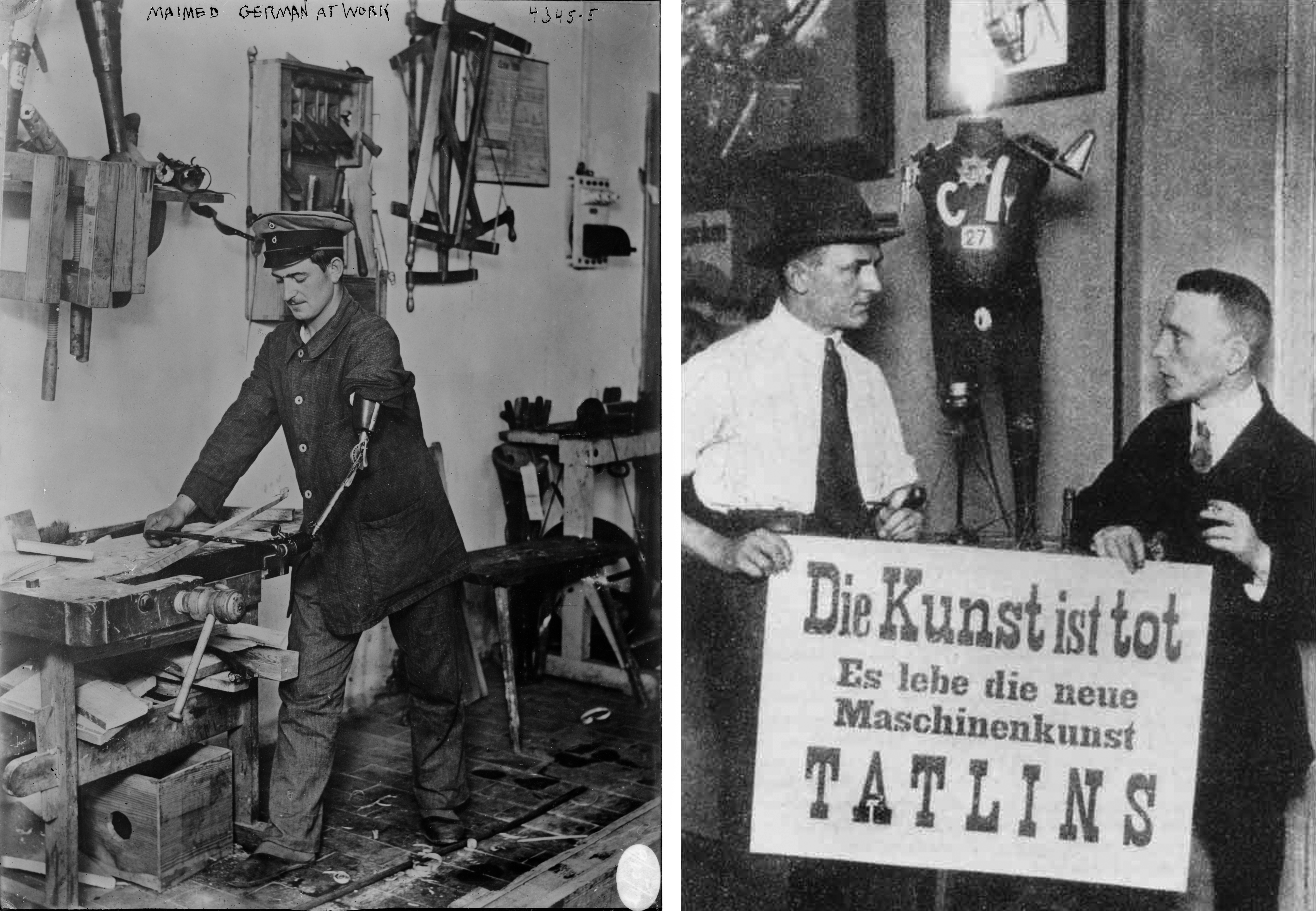

Also visible in the Dada Fair photograph are two works that refer to another lingering effect of the war: the common sight of soldiers returning with disfiguring injuries, amputated limbs, and artificial body parts. On the right edge of the photo is a sculpture of a man by George Grosz and John Heartfield entitled Middle-class Philistine Heartfield Gone Mad. The torso is a tailor’s dummy decorated with symbols of war (a revolver, an iron cross, an insignia for the Black Eagle Order), while much of the rest of the body is made of machine parts: a metal pipe for a leg, a lightbulb for a head, and dental prostheses for genitals. The figure also wears a dehumanizing number for identification. The assemblage simultaneously suggests a wounded soldier with multiple prostheses, and a cyborg whose infatuation with technology has overwhelmed its humanity.

Left: Photo of a disabled German soldier using prosthesis in a carpentry shop in Konigsberg, Prussia (Library of Congress); George Grosz and John Heartfield, photo at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin, 1920 in front of their sculpture Der wildgewordene Spiesser Heartfield (Elektro-Mechan. Tatlin-Plastik), 1920

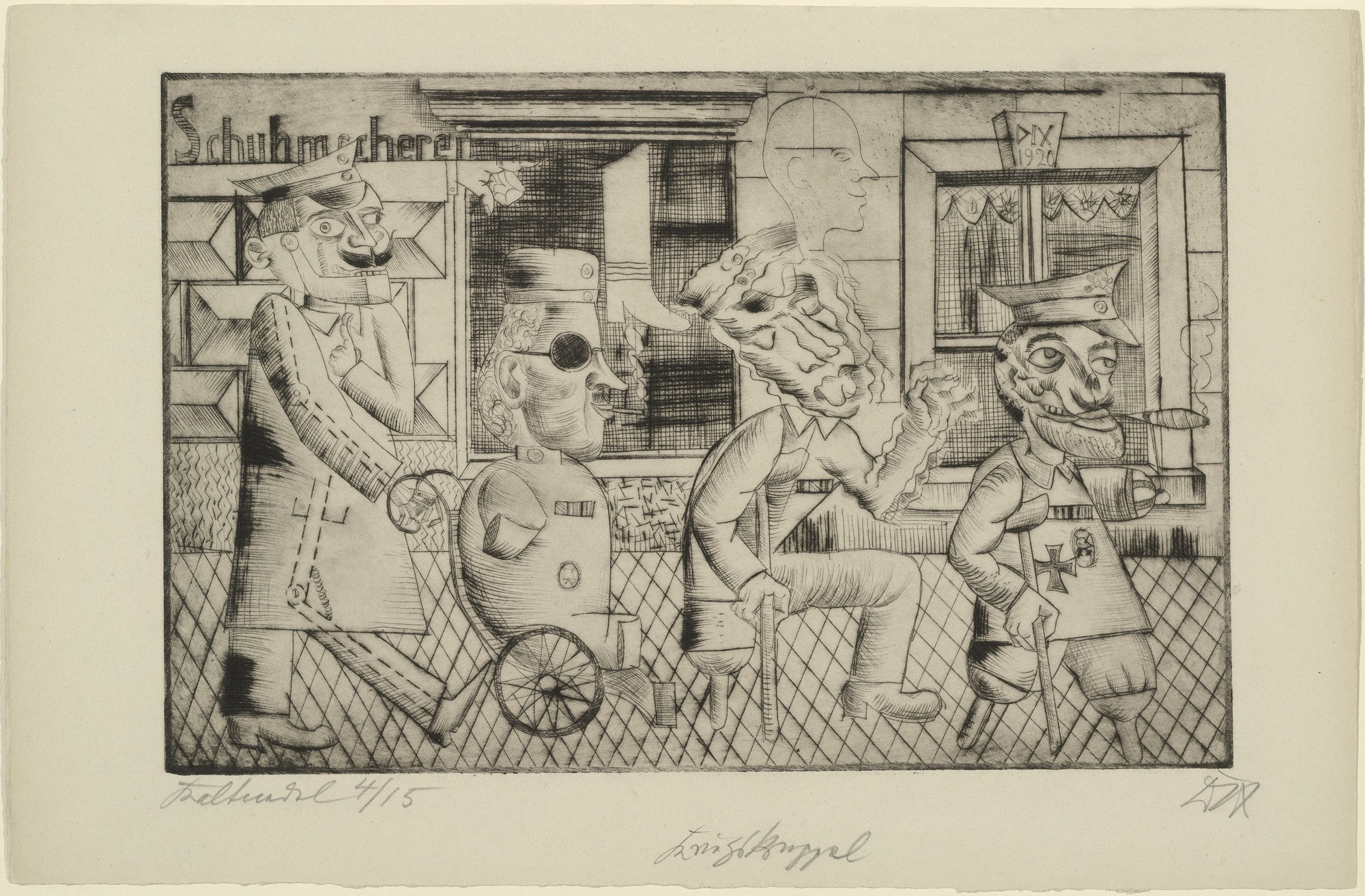

On the left of the Dada Fair photograph is the painting War Cripples, or 45% Fit for Duty, by Otto Dix, who served as a machine gunner in the Battle of the Somme, during which one million men were killed or wounded. Dix’s original painting was destroyed, but a contemporary print shows how it called attention to the war wounded. Although they are attired in the splendor of their full-dress uniforms, large portions of the soldiers’ bodies have been replaced by prosthetics, and what at first may appear to be “modernist” distortions of their faces are not. The man at the far left has a permanently staring glass eye, and his jaw has been replaced by a crude early attempt at plastic surgery that is only slightly less disturbing than the mangled face of the man at the far right. To his left, permanent tremors afflict a man with “shell shock” (now known as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), and next to him a quadriplegic man is being wheeled past a shoe store he will never need to visit. It is hard to overstate the contrast between this image and traditional, heroic depictions of soldiers.

Images such as these show how the Dadaists’ mistrust of authority, technology, and nationalism, combined with their willingness to shock and offend, were effective in creating devastating social and political criticism in postwar Germany.