House of the Eagles, sacred precinct of Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City), c. 1400–1521, and Mictlantecuhtli and Eagle Warrior, c. 1400–1521, terracotta and plaster, life-size, found in the House of the Eagles (The Templo Mayor Museum, Mexico City); a conversation between Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker

Essay by Dr. Maya Jiménez

Eagle Warrior from the House of the Eagles, c. 1400–1521 C.E., Tenochtitlan (today, Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Eagle Warrior is a life-sized ceramic sculpture made by Mexica (sometimes called Aztec) artists that shows a warrior dressed in an eagle costume. Made of terracotta, a type of earthenware known for its reddish color, the life-sized Eagle Warrior was originally painted and adorned with feathers and weapons. His outstretched wings and arms suggest a gesture of flight. This sculpture was discovered during excavations at the main Mexica temple, called the Templo Mayor. This temple was located in the ceremonial center of Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Mexica empire. The Templo Mayor consisted of a twin-towered stepped pyramid dedicated to Tlaloc, the god of Rain, and Huitzilopochtli, the patron god of the Mexica, usually associated with war and fire.

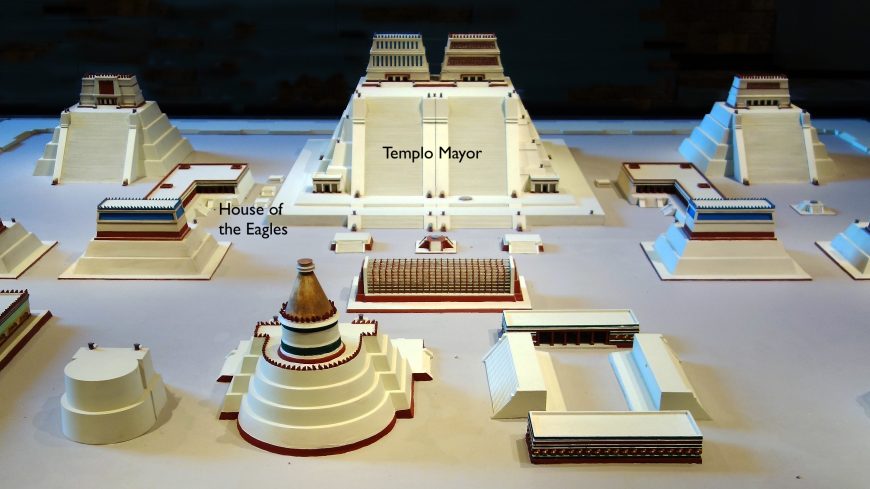

Model of the Sacred Precinct in the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan, today, Mexico City (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The sculpture was recovered at the House of the Eagles, the meeting place of eagle and jaguar warriors, two of the most prestigious of the Mexica military classes. The House of the Eagles was just beside the Templo Mayor, and highlighted the association of the Mexica’s most important temple with warfare. The Templo Mayor itself symbolized warfare in its combination of Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli.

House of the Eagles, c. 1400–1521 C.E., Tenochtitlan (today, Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For the Mexica, the symbol for war was water and fire, called the atl-tlachinolli in Nahuatl, the language of the Mexica. A meeting space for eagle and jaguar warriors next to the Templo Mayor advertised the important role that the military classes played in Mexica culture more generally and in maintaining Mexica power over conquered peoples.

Warrior ranks

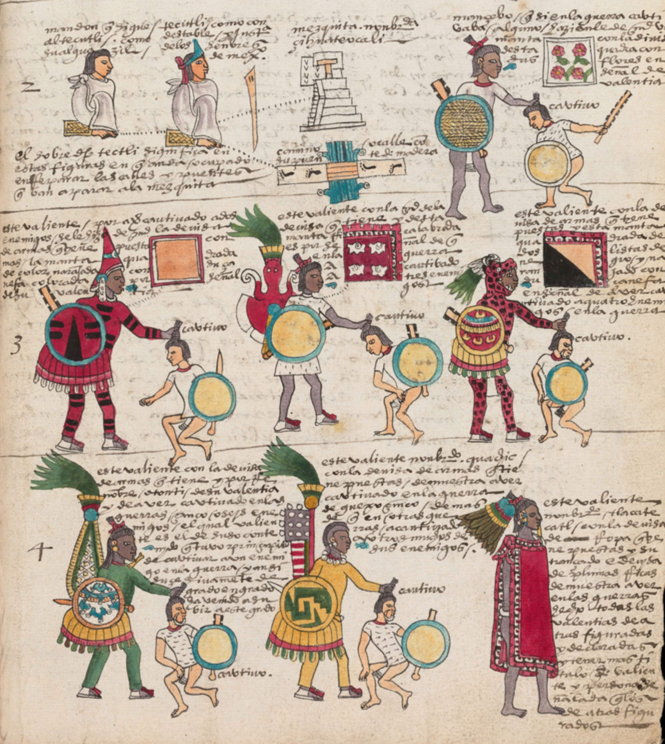

Warriors, Codex Mendoza, Viceroyalty of New Spain, c. 1541–1542, pigment on paper (© Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford)

While the Mexica had no standing army, they did have elite warriors with extensive military and martial arts training who fought in “flowery wars,” a ritualistic form of warfare that consisted of capturing victims and sacrificing them to the gods.

Our understanding of the role of the eagle warriors is largely based on colonial sources (or written sources made after the Spanish conquest in 1521), including the Codex Mendoza, (c. 1541–42). This book documents pre-invasion Mexica culture but was commissioned by Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy of New Spain. It should be kept in mind though that the Codex Mendoza, while a critical historical document, is not politically nor culturally neutral. According to this source the goal of the eagle warrior was to capture the greatest number of captives, who would then be sacrificed to the Mexica gods. Warriors rose in rank according to the number of captives they acquired. This ranking system is documented in the Codex Mendoza, which illustrates the different military ranks and their corresponding war suits, determined by the number of captives.

In the second to last register, for example, the warrior in the red suit is credited for capturing two victims, while the jaguar warrior at the far right captured four. In the last register, the warrior at right is of the highest rank, yet he is dressed in civilian clothes, a reference to his aristocratic ancestry. While all warriors were equipped with shields and obsidian weapons, their war suits identified their military rank and social status.

Symbolism of the war suit

Eagle Warrior from the House of the Eagles, c. 1400–1521 C.E., Tenochtitlan (today, Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, the war suit served a symbolic function, since it was believed that in dressing like an eagle or a jaguar, the warrior adopted the power and skill of their assigned animal, thus ensuring a more successful hunt. The symbolism of the war suit was further emphasized by its materiality, since most warriors, except for the nobility, wore suits made of animal skin. The eagle warrior not only acted like an eagle, but also literally resembled one.

Original appearance

In comparison to the warriors seen in codices, the Eagle Warrior may appear somewhat tame at first. Lacking the colors, patterns, and weapons of the warriors of the Codex Mendoza, the Eagle Warrior does not seem have the menacing appearance that these soldiers may have actually possessed. But we have to remember that the sculpture was originally painted and covered in feathers, and so it would have had a more life-like appearance when placed in the House of the Eagles.

Bench from the House of the Eagles, c. 1400–1521 C.E., Tenochtitlan (today, Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mictlantecuhtli from the House of the Eagles, c. 1400–1521 C.E., Tenochtitlan (today, Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Eagle Warrior stood near the doorway of the House of the Eagles, likely functioning as a guardian figure. He stood atop a bench that was decorated with relief sculpture showing warriors as they advanced towards a ball (called a zacatapayolli) into which they placed bloodletting implements. Warriors would have pierced parts of their body, such as their tongue or ears, to let blood onto paper, which would then be burned. The blood was offered to the gods as an act of penance because the Mexica believed that the gods demanded blood in return for their creation of the world.

Another life-size terracotta figure stood at a second doorway in the House of the Eagles, but instead of showing an eagle warrior it is the god of the Underworld, Mictlantecuhtli. At almost six feet tall, the skeletal god is as imposing as the Eagle Warrior, if not more so. He leans slightly forward, his clawed hands raised and his mouth slightly open. Originally, hair or paper decorations would have been placed in the holes on top of his head. Like the Eagle Warrior, Mictlantecuhtli displays the same skill in firing terracotta on a large scale.

Though much of the original splendor of the armed Eagle Warrior has been lost, one can only imagine the imposing appearance of this sculpture hovering at the entrance as actual warriors gathered together. Both the sculpture of the Eagle Warrior and Mictlantecuhtli testify to the ways in which sculptures of warriors and gods played an active role in Mexica life.

Important terms:

- Mexica/Aztec

- House of the Eagles

- Tenochtitlan

- Sacred Precinct

- Mictlantecuhtli

- jaguar and eagle warriors

- terracotta

- Mictlan

- bloodletting

- zacatapayolli

Additional resources:

Introduction to the Aztecs (Mexica)

Introduction to the Templo Mayor

Tenochtitlan on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Aztec stone sculpture on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Aztec Empire from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Templo Mayor virtual visit (in Spanish)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:06] We’re in Mexico City, and we’ve just walked through the House of the Eagles, and are now looking at two very large ceramic figures that were originally in the House of the Eagles but are now in the Museum of the Templo Mayor.

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:19] The House of the Eagles was part of the sacred precinct in the center of the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan. Right next to the House of the Eagles, or very close to it, was their main temple, the Templo Mayor.

Dr. Zucker: [0:31] The House of the Eagles was a place where an elite group of warriors, the eagle warriors, gathered and performed a variety of different rituals, including bloodletting.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:40] Eagle warriors were one class of elite warriors. The others were jaguar warriors. They would come to this particular structure and make offerings of their own blood as well as gather together. It’s really important for understanding both the structure itself and the figures that we’re seeing here in the museum.

Dr. Zucker: [0:56] You would have walked up a broad set of stairs and walked past a kind of colonnade into a shallow hall. Then there would have been an opening, a doorway, and on either side of that doorway would have been two of these eagle figures flanking as guardians.

[1:10] If you entered in further, there would have been another doorway and there would have been a pair of these two figures of the god of the underworld.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:19] This god of the underworld, Mictlantecuhtli, or Lord of the Underworld, is similar to the two terracotta sculptures of the eagle warriors. They’re both standing upright, but leaning forward.

Dr. Zucker: [1:29] Making them even more aggressive, even more intimidating, at least to me.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:33] If we go back to the eagle warrior terracotta sculpture here, we can see that it was made in several pieces and then put together. Then stucco was applied to the outside of the terracotta to imitate eagle feathers.

Dr. Zucker: [1:45] That, perhaps, would have been painted in turn.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:47] Then this individual is wearing what looks like a feather costume on his arms and then this wonderful headdress of an eagle head from which his own face emerges.

Dr. Zucker: [1:57] It creates this wonderful pairing of the natural world and our world. In all of these figures, there’s this slippage between the supernatural and between the world in which we walk.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:06] Unfortunately, none of these costumes survive, but we know what they would have looked like based on early colonial codices that show these eagle warrior costumes.

Dr. Zucker: [2:14] I love the knees with the claws coming out of them. Then, attached to these figures would have been real feathers.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:20] It’s entirely possible that real feathers could have been attached to this warrior. If we’re looking at the other figures of Mictlantecuhtli, or this Lord of the Underworld, he is very different than the eagle warrior.

Dr. Zucker: [2:31] We see an emaciated figure. This is almost skeletal.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:34] He is partially defleshed. We have this skeletonization, which you really see in the upper portion of the torso, where you see the exposed rib cage and this interesting element that’s hanging out of his rib cage.

Dr. Zucker: [2:46] The liver hangs down pendulously and really activates the figure, and emphasizes the fact that he is leaning forward so far.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:53] As he’s leaning forward, his arms are raised, and his clawed hands are held upwards. His face also shows evidence of this defleshing because his mouth is lipless, but we see his teeth.

Dr. Zucker: [3:04] The head is too large for the proportions of the body, the hands are too large for the proportions of the body, all of this making him tremendously present and active.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:13] What we see today are holes on top of the head. If we were seeing this in the 15th century, when this sculpture would have been created, there would have probably been paper banners, or some type of paper adornment placed inside of these holes. The head actually would have been emphasized even more so than it is today.

Dr. Zucker: [3:29] It’s also important to remember that we’re seeing here in the museum has been cleaned up, because when these figures were unearthed, they were coated with layers of human blood.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:38] Scientific analysis revealed this sticky, thick substance that was originally found on this Mitlantecuhtli sculpture was in fact human blood, most likely from the offerings that the eagle warriors were making by piercing, say, their tongues.

[3:51] Blood offerings here by these eagle warriors would have been to give back to the deities, to help to feed them, to help sustain the cosmos and life itself.

Dr. Zucker: [3:59] Bloodletting was a heavily ritualized event and did not necessarily have negative connotations.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:04] No, and in fact, some of the other remarkable things that we see here in the House of the Eagles are these carved benches in relief, painted in different colors. We see them throughout the building.

[4:14] What they’re showing are warriors in procession, marching and converging upon these half-sphere objects that are actually grass-reed balls into which you would place bloodletting instruments, so the very instruments they were piercing their tongues with.

Dr. Zucker: [4:29] Needles that would have been used to pierce the skin.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:31] Something like a stingray spine or a thorn to pierce the tongue, or maybe the earlobe.

Dr. Zucker: [4:36] There’s real continuity between these large figures and these painted reliefs along the benches, which are found in every room within the House of the Eagles.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:45] If we come back to the Mictlantecuhtli sculpture, this individual who’s partially defleshed, I want to note that the liver was a location of one of the three souls.

[4:54] The Aztecs believed there were three souls: one in the head, one in the heart, and one in the liver. The liver had associations with Mictlan, the lowest level of the underworld where Mictlantecuhtli lived.

[5:06] What’s wonderful about these particular figures is that they’re in terracotta. The Aztecs are so famous for their monumental stone sculpture, and yet we clearly see here that they were also extremely capable artists working in terracotta.

Dr. Zucker: [5:18] The scale of these figures, their sense of presence, their animation, it really brings the Aztecs to life.

[5:24] [music]