Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz, 1928, oil on canvas, 96.5 x 66.7 cm (Fisk University and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz

[0:00] [music]

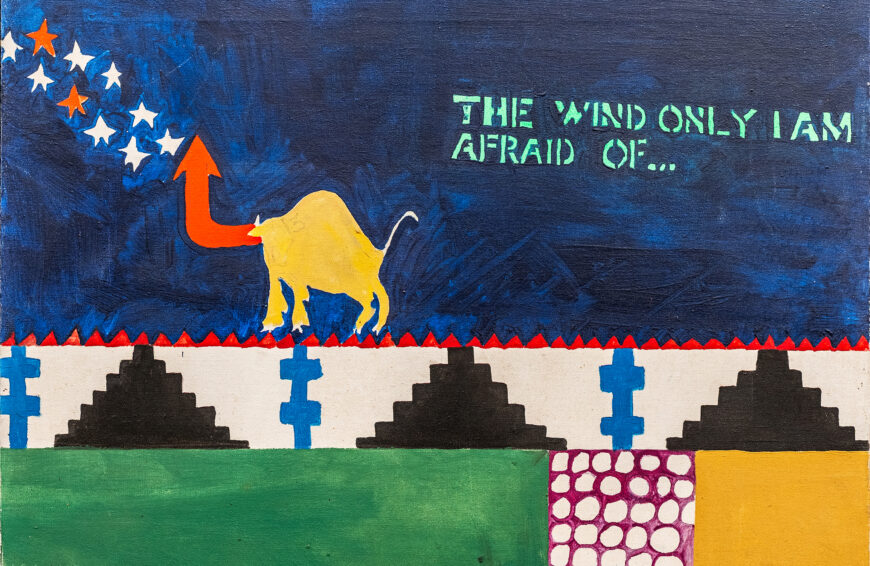

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:16] We’re at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, looking at a painting by Florine Stettheimer. It’s a portrait of Alfred Stieglitz, one of the most important photographers, gallerists, and modernists in early 20th century American history.

[0:19] This painting is part of the Alfred Stieglitz Collection, co-owned by Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, and by Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Dr. Jen Padgett: [0:28] It was a painting that Stieglitz owned himself and that was gifted to him by Stettheimer. In the painting, she captures the sense of Stieglitz at the center of a circle of artistic activity within New York.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] Stieglitz had created a circle of many of the most important American artists and photographers through a series of galleries and salons in New York before modern art had been established here.

Dr. Padgett: [0:59] And for Stettheimer, much of that activity was around gatherings in the home that she shared with her mother and two sisters. They would hold salons to discuss the most exciting developments around art and culture during that moment.

[1:07] Painting, for her, was about these personal reflections and connections. Many of her paintings depict individuals within her circle and images of family enjoying leisure.

Dr. Zucker: [1:18] That is the case with this portrait. This is a portrait of Stieglitz, a close friend, and the references that are contained within this painting are ones that this entire circle would have recognized.

Dr. Padgett: [1:28] In the individual boards that have the names of artists, one is Marsden Hartley, written in a rather decorative script. One is the letters D-O-V-E, of Arthur Dove’s name, another painter within this circle around Alfred Stieglitz. Then one is Paul Strand, a photographer who worked closely with Stieglitz.

Dr. Zucker: [1:51] Then, in the upper part of the painting, there are works of art that are hanging on the walls. On the left, we see two framed paintings by John Marin, and then, directly in back of Stieglitz, there are references to his wife at this time, Georgia O’Keeffe, a painting with a large leaf form that seems to be very close to the kinds of paintings that O’Keeffe produced at Lake George.

[2:12] Then, over his other shoulder, you can read the word O’Keeffe, and just beside that, the profile of that painter.

Dr. Padgett: [2:15] Stettheimer, Stieglitz, and O’Keeffe were actively writing letters to each other during this time. Stieglitz was at Lake George at the time that Stettheimer was working on the painting.

[2:24] That sense of geography and Stieglitz’s connection to place is something that Stettheimer references, where she has the stepped profile of a skyscraper, emphasizing Stieglitz’s association with the city of New York.

[2:41] Then, further into the background, she shows a horse race, which would reference his time at Lake George and nearby Saratoga.

Dr. Zucker: [2:44] Saratoga, at this time, was a fashionable place for the wealthy in New York to summer, for its racetrack, and for its hot springs.

Dr. Padgett: [2:51] Some of the figures we can recognize because they appear in other Stettheimer paintings, such as the portrait of Henry McBride wearing glasses, with his arms crossed.

Dr. Zucker: [3:02] McBride was an important critic of modernism and was a close friend of Stettheimer’s and the Stieglitz circle.

Dr. Padgett: [3:08] Stettheimer emphasized the queer figures within this circle, those who were gay or bisexual, who she embraced within a more inclusive circle of her salons.

[3:19] You can see, on the left-hand side, the cane, hand, and foot surely belong to Charles Demuth, who is a painter within the circle. Demuth walked with a cane because of a hip infirmity, but here, it also reads as an accessory of a dandy figure, a sharply-dressed individual.

Dr. Zucker: [3:38] The identity of the figure in green on the right is less secure, but we know that everybody who looked at this painting from this circle would have recognized, presumably, the pattern on the sock and the reference to the ermine cuff and the yellow glove.

Dr. Padgett: [3:51] We think it might have been Baron Adolph de Meyer, who was another queer figure within this circle. A photographer who often dressed fashionably and created images for fashion magazines.

Dr. Zucker: [4:08] Both of those fragmentary figures are really striking because, beside the leaf in the O’Keeffe painting, these are virtually the only touches of color. The exception being the date just at the feet of Stieglitz. The painting is black and white, just as Stieglitz’s photography was black and white.

[4:20] This is a portrait that goes far beyond the idea of likeness. This is a portrait that is meant to express what was important to this man.

Dr. Padgett: [4:28] That choice of color was also a major departure for Stettheimer. Many of her other paintings feature rather electric colors and pastels, so seeing this painting, in contrast, emphasizes how she was thinking about it in different ways because of the sitter’s identity.

[4:44] Stettheimer wasn’t depicting Stieglitz as he looked, he never sat for the portrait. She depicts him much younger than his age of 64 at that time. It’s about capturing the sense of an individual, the energy behind them, and not just one-to-one likeness.

[4:59] This really dramatic cape that he wears was a bit of a signature for him, and Stettheimer heightens that by making him the large figure. The way that his hand emerges from within the folds of the fabric draws you directly in to the center of the work.

Dr. Zucker: [5:17] Although she had been classically trained as an artist, she is playing fast and loose with the anatomy of the figures. Obviously, Henry McBride is much taller than he would have been, but even the main figure, Stieglitz, is attenuated. He’s given a kind of elegance and a drama that goes beyond the naturalistic.

Dr. Padgett: [5:36] I can’t help but be drawn to the detail of his feet, which poke out almost daintily from the bottom, that seems to add a sense of whimsy.

Dr. Zucker: [5:38] In fact, the way that he walks out towards us almost suggests this as a kind of stage, that she is staging a performance that is Stieglitz and his circle.

Dr. Padgett: [5:52] We know that performance is happening within a space that was one of Stieglitz’s galleries, which he operated between 1925 and 1929. You can see that through the number 303, which was the room number, and then his name underneath that as the hand with the ermine cuff opens the door to “The Room,” which was the nickname given to Stieglitz’s Intimate Gallery.

Dr. Zucker: [6:12] This portrait is so important, because although its elements would have been seen as playful and familiar to Stieglitz and his circle for us, it’s a window that allows us back into this world.

[0:00] [music]

| Title | Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz |

| Artist(s) | Florine Stettheimer |

| Dates | 1928 |

| Places | North America / United States |

| Period, Culture, Style | Modernisms / 291 |

| Artwork Type | Painting / Portrait painting |

| Material | Oil paint, Canvas |

| Technique |

This work at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Watch a video and read about Stieglitz’s photograph The Steerage.

Learn about the artists referenced in this portrait—Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth, and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Loading Flickr images...