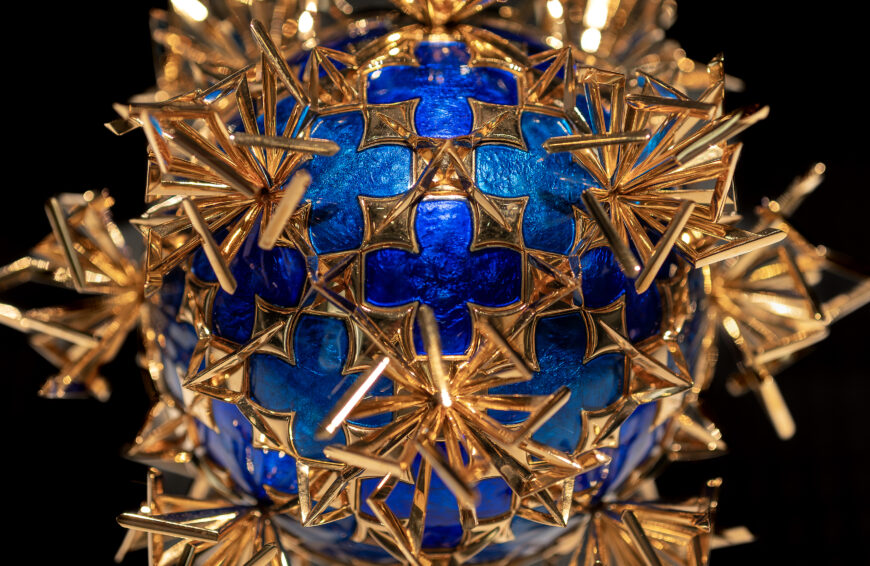

Raoul Hausmann, Spirit of the Age: Mechanical Head, 1919, wooden mannequin head with attached objects, 32.5 x 21 x 20 cm (Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the Pompidou Centre in Paris, looking at a sculpture from 1919 by Raoul Hausmann, “Spirit of the Age: Mechanical Head.”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:13] This looks so familiar to us, the idea of merging our bodies with technology, that it might be hard to recapture how this appeared in 1919.

Dr. Zucker: [0:22] In the immediate aftermath of a terrible tragedy. The First World War, the Great War, had just ended. Germany was defeated, but it wasn’t just a military loss. So much of the adult population had seen death firsthand.

Dr. Harris: [0:35] Even people who hadn’t been in the war itself were faced with people coming back from the war who were maimed, who were scarred.

Dr. Zucker: [0:43] This was a war where technology played an enormous role, from the use of tanks and machine guns to mustard gas.

Dr. Harris: [0:50] The movement that emerged in Europe during and after the war, Dada, is a direct response to the insanity of the war itself. A reckoning with the confidence before the war that humanity could never engage in such brutality. In the 19th century, there was a sense that things would get better because of technology.

Dr. Zucker: [1:10] There had been this idea that culture was progressive, that science, the rational, was in a way our savior.

Dr. Harris: [1:16] And governments, too. The idea of governments creating the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people, the rise of democracy. These were seen as positive developments that would elevate mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [1:29] But that idealism vanished in the wake of the First World War. The war was seen as pointless, as absurd, having had no practical value, where governments disposed of people as if they were pawns.

Dr. Harris: [1:40] Berlin was one of the important centers of the Dada movement, with this interest on the irrational, the senselessness of life in the wake of World War I.

Dr. Zucker: [1:49] Raoul Hausmann was one of the leaders of Berlin Dada, and this is his most well known work. We see a head, but it’s not a head that he carved. It’s the head of a mannequin, perhaps a dummy that would have been used for a wig or in a tailor shop. It has blank stare, and that blankness almost feels militaristic, as if we’re looking at a soldier at attention.

Dr. Harris: [2:07] It has a sense of being one of many, like soldiers all wearing the same uniform.

Dr. Zucker: [2:13] But here, instead of wearing a uniform, he has a series of objects attached to his head that look as if he’s not wearing them so much as they are part of him.

Dr. Harris: [2:22] There’s a screw on one side and a nail on the other that reminds me, at least, of the wounds of the Crucifixion.

Dr. Zucker: [2:28] But also remind me of Frankenstein, of the uneasy relationship between the human body and technology going back to the late 18th century, the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

Dr. Harris: [2:38] We have mechanical appendages here for the ears.

Dr. Zucker: [2:41] On one side, dials, perhaps from a camera. On the other, a type cylinder.

Dr. Harris: [2:46] And that type cylinder is in a lovely little case, but on each side, these forms really do look ear-like and yet they’re mechanical.

Dr. Zucker: [2:53] I can’t help but think that the artist was thinking about typewriters and cameras. That media is somehow being placed directly into the mind.

Dr. Harris: [3:01] Without forethought, without any kind of intervention of the soul, of individuality.

Dr. Zucker: [3:07] Look how blank he is. There is no soul that’s presented here.

Dr. Harris: [3:10] Today, it’s impossible not to think about the power of social media on our perceptions and how we view the world.

[3:17] My favorite part is the empty cup that acts like a little bowler hat.

Dr. Zucker: [3:21] It’s right at the top of his skull, and engraved on it is a little heart, the only sense of humanity playfully represented here.

Dr. Harris: [3:27] And on something that is collapsible, as though the human heart were something that you could replace with mechanization.

Dr. Zucker: [3:35] That cup is just a simple piece of inexpensive tin; stretched across the forehead is [a] segment of a tape measure. On the right is a ruler. All these references to man’s supposed control of nature. It’s an expression of just how displaced that hope had become in 1919.

Dr. Harris: [3:50] The number 22 attached right on the forehead in between that tape measure and what look like the gears of a clock give us a sense that we’re not looking at an individual.

Dr. Zucker: [4:00] But a number.

Dr. Harris: [4:01] On the back of the head we see a wallet made out of crocodile skin, so you have the sense that part of what controls the mind, too, is money.

Dr. Zucker: [4:10] Dada artists were commonly indicting modern capitalism as a driving force in the violence of the war and the corruption of German society, of European society more broadly.

Dr. Harris: [4:19] And so we have here this image that speaks to our modern discomfort with the technologies that we’ve created and the potential harm and dehumanization of those technologies.

Dr. Zucker: [4:30] With a kind of absurdist visual language.

Dr. Harris: [4:32] That was very typical of Dada. This interest in the absurd, the irrational.

Dr. Zucker: [4:37] This sculpture and the very name “Dada” references nonsense and is meant to be a counterweight to our reliance on rationality, which in 1919 had clearly failed.

[4:47] [music]