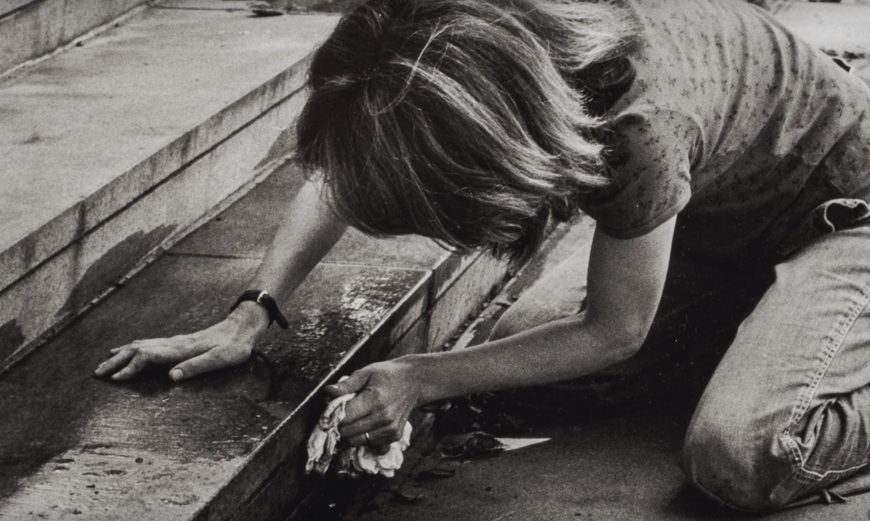

Ivan Cardoso, stills of a man dancing before a mural of the Brazilian flag, from the documentary H.O., 1979, 35mm film transferred to video (color, sound), 13 minutes

Samba and the favela

A vibrant soundtrack of samba plays as Afro-Brazilian men and women rhythmically dance and twirl while wearing colorful, asymmetrical fabric assemblages. One man waves billowing orange, red, and yellow textiles over his arms as he dances in front of a painted mural of the Brazilian flag. A woman attired in a similar combination of green and red cloth spins around joyously to an energetic rhythm. Another man leans backwards with his legs spread wide, his arms enveloped in red plastic flaps which unfold like wings as he opens them, before hurling his body into dance with ecstatic abandon.

Ivan Cardoso’s HO, a documentary film about the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica. It shows Oiticica and his collaborators wearing the Parangolés. Ivan Cardoso, H.O., 1979, 35mm film transferred to video (color, sound), 13 minutes

These sequences appear in H.O., a documentary film about the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica. They show people wearing one of Oiticica’s most iconic artworks: parangolés, or wearable, experiential garments that he initiated in 1964 and continued working with for the rest of his career. Parangolés are capes, or cloak-like layers of different materials that were intended to be worn by moving and dancing participants. They were made of colored and painted fabrics, as well as nylon, burlap, and gauze. Some contained political or poetic texts, photographs, or painted images, along with bags of pebbles, sand, straw, or shells. They also sometimes took the form of flags, banners, or tents.

Hélio Oiticica, Parangolé P4 Cape 1, acrylic on canvas, fabric, nylon, rope and plastic, 93 x 160 x 10 cm (MAM Rio Collection)

It was through learning to dance the samba that Oiticica developed the parangolé. He said that dancing freed him from art’s “excessive intellectualization.”[1] He learned about samba through his contact with the community of Mangueira, a favela (Brazilian slum) located on the outskirts of his hometown of Rio de Janeiro. He began visiting the favela in an attempt to escape what he perceived as the constraints of Rio de Janeiro’s art scene. Oiticica was white, middle class, and educated, while the favela’s inhabitants were mainly Black, poor, and uneducated. Despite the significance of this disparity, Oiticica developed friendships with a number of residents and was eventually accepted by the community. He learned to samba and even became a passista (a highly skilled dancer who performs in Brazilian Carnival) in the Mangueira samba school (a club for dancing and playing samba in the annual Carnival parade).

Hélio Oiticica, Parangolé P1 Cape 1, canvas and plastic (Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural, 2020)

Oiticica asserted that the favela made him more aware of social inequities. As a result, the concept of “marginalization” became fundamental to him, especially as a gay man. He began to associate the marginalized position of the artist in society with the marginalization of favela communities. This was thrown into sharp relief when Oiticica invited some friends from Mangueira to help him inaugurate the parangolés by dancing in them in their first public presentation at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro for the opening of the exhibition Opinião 65 (Opinion 65). The dancers were refused entry into the building, revealing the institutionalized racism and classism pervading Rio de Janeiro at the time. Even the word “parangolé” (meaning a sudden agitation, an unexpected situation, or a dance party) was rooted in marginalization: he adopted the term when he saw a piece of cloth with the word on it hung by a beggar on the street. Oiticica’s experience of the marginality of Rio de Janeiro’s most impoverished inhabitants awakened him to the social and ethical implications of art.

Brazilian Concrete and Neoconcrete art

Influenced by Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevich, Oiticica started his art career in the late 1950s making paintings in a style known as Concrete art. He soon became frustrated by the style’s rigidity, and he joined a new movement (organized by artists Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, and others) called Neoconcrete art, which would influence the development of his parangolés.

Neoconcretism called for more sensuality and personal expression in geometric abstraction. The movement’s manifesto by poet Ferreira Gullar criticized Concrete art’s rationalism, advocating instead for subjective interactions between viewers and artworks that were influenced by French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception. Merleau-Ponty describes perception as rooted in bodily experience. Neoconcrete art helped to spark a new interactivity between the art object and the viewer-participant, who was now encouraged to touch and manipulate artworks. For instance, Oiticica’s friend Lygia Clark added hinges and flaps to her geometric aluminum sculptures called bichos (or critters), so that they could be manipulated and transformed by the spectator.

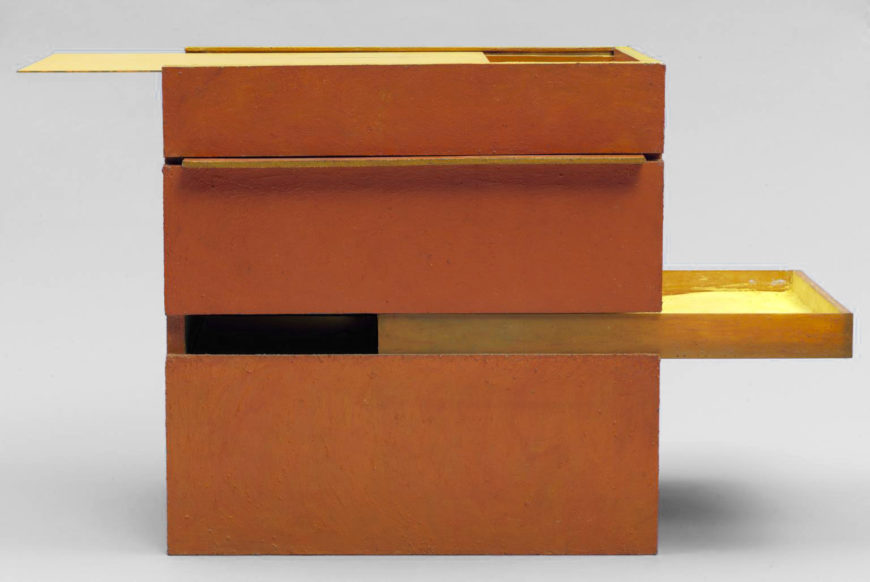

Hélio Oiticica, B11 Bólide Box 09, 1964, Wood, glass and pigment, 498 × 500 × 340 mm (Tate)

Oiticica’s works from this time are marked by their transformation from two-dimensional grid-like paintings to various forms he titled bólides, that include boxes with drawers containing various materials that could be touched. He also created closed environments that could be physically entered by the spectator (such as his PN1 Penetrável, 1960), demonstrating his shift toward increased audience participation. With the parangolé, the spectator’s moving body became a part of the work by mobilizing the cape as color in motion, and activating what Oiticica described as a “wearing-watching cycle” among participants.[2]

From participatory art to political resistance

The same year that Oiticica developed the parangolé, the Brazilian military (with U.S. support) launched a coup d’etat, initiating a twenty-one year military dictatorship. It was against the backdrop of increasing political repression that Oiticica began engaging the spectator as a participant in his works, an approach known today as participatory art. This approach to art engages the audience in the creative process so that they become collaborators in the work. A common interpretation of the parangolés is that they were intended to liberate their wearers from the repressive military regime by enabling them to become aware of their capacity to rebel.

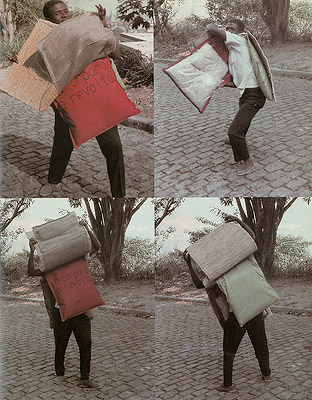

Hélio Oiticica, Parangolé P15, Capa 11, Incorporo a Revolta, 1967. Photographs by Cláudio Oiticica (Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural, 2020)

Some parangolés even included political statements such as “Of Adversity We Live” (1965) or “I Embody Revolt” (1967). Such statements went unobserved by authorities because state-sponsored censorship initially focused more on the press and pop music than on visual art. More widespread censorship gained momentum only after 1968, when the dictatorship enacted the Institutional Act Number 5, leading to the imprisonment and torture of dissidents. Many artists, including Oiticica, left Brazil due to the increasing oppression. He travelled to London to mount his solo exhibition The Whitechapel Experiment at Whitechapel Gallery in 1969.

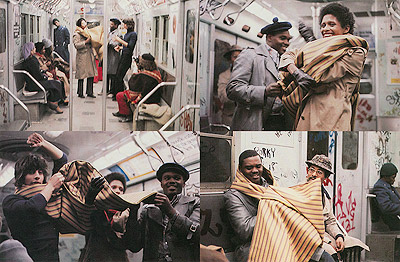

Hélio Oiticica, Parangolé Capa 30, 1972. Photograph by Andreas Valentin (Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileiras. São Paulo: Itaú Cultural, 2020)

Parangolés in New York and beyond

Oiticica came to New York in 1970 to participate in Information, a group exhibition of conceptual art at The Museum of Modern Art. After winning a Guggenheim Fellowship the same year, he stayed in exile in the city for the next eight years. In 1973, he organized an excursion with some friends into the subway system in order to invite riders to try out the parangolés.[3] The interactive encounter represented a continuation of his exploration of the intersections of art and life and his interest in engaging non-art audiences. Much like the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, in the 1970s New York’s heavily-graffitied subway had the reputation of being a site of criminal activity, its denizens thought to be beggars, drug addicts, and gang members. Bringing the parangolé into that space attested to Oiticica’s continued socio-political commitment to engaging marginalized people through liberating experiences. He would continue to play and experiment with his parangolés until his untimely death in Rio de Janeiro in 1980 at the age of forty-two.

Parangolés demand to be worn and moved in, not observed as lifeless objects hung on a wall for display. Today, they are usually only seen in documentary photographs and films, rather than worn by the spectator. When samples are available to try on in exhibitions, they rarely match the lively energy they once inspired. Even so, they continue to have a lasting impact on participatory and socially engaged art practices.