Jackson Pollock and Peggy Guggenheim in front of Mural, c. 1944, in Guggenheim’s New York City townhouse, (photo: George Carger)

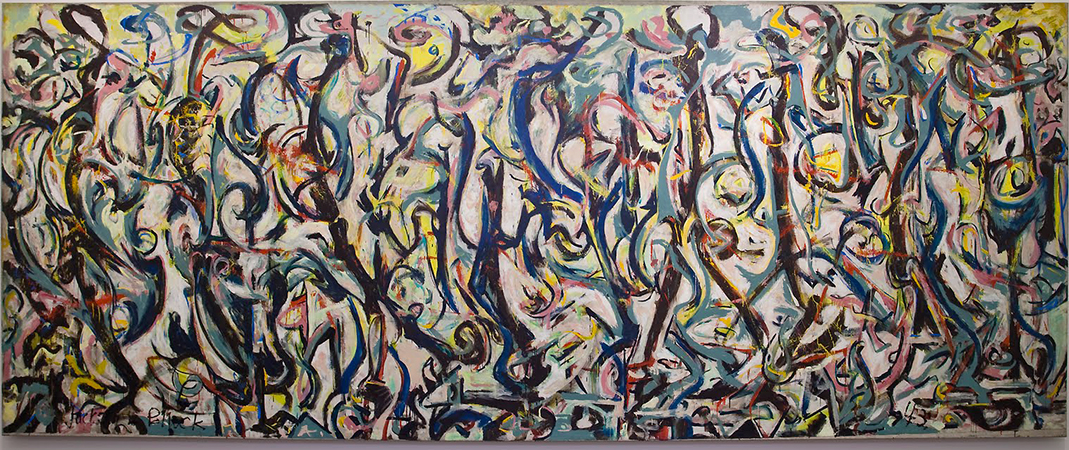

Imagine living in New York in the early 1940s. Your friend, the art dealer Peggy Guggenheim, is excited to show you her latest acquisition by an up-and-coming artist. You can’t miss it on the right-hand wall in the long, narrow corridor of her townhouse. Nearly twenty feet in length and eight feet high, it consumes the space and takes your breath away. In the words of art critic Clement Greenberg, “I took one look at [Mural]…and I knew Jackson was the greatest painter this country had produced.”

Creative decisions

The artist, Jackson Pollock, had studied with the American muralist Thomas Hart Benton as well as with the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros at his experimental workshop. Later Pollock was employed through the Federal Art Project, part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration. That ended in January 1943 and, desperate to make a living, Pollock took a job as a janitor and handyman at The Museum of Non-Objective Art (which is now named the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum for its principal benefactor, Peggy’s uncle). Peggy Guggenheim’s assistant Howard Putzel became aware of Pollock’s work, and introduced him to the art patron who would champion his career. For this first commission she envisioned a mural painted directly on the wall, but her friend, the artist Marcel Duchamp, wisely suggested a painting on canvas that could be removed and transported in the future. She purchased the oversized Belgian linen canvas, thereby dictating the size of the work, but all other creative decisions were at the artist’s discretion. Pollock received this commission mid-July 1943, and by the end of that same year the painting was hanging in her townhouse. In 1951 Peggy Guggenheim gifted the painting to the University of Iowa.

Jackson Pollock beside the canvas for Mural, 1943 (photo: Bernard Schardt)

Conservation

Mural began to deteriorate in the 1970s. Paint was starting to flake, and the weak original stretcher caused the canvas to sag. In 1973, conservators at the University of Iowa adhered a lining canvas with wax-resin to the reverse side for stability, replaced the original stretcher, and applied varnish to the surface of the painting. However, in recent years Mural’s need for additional care was apparent, and in July 2012 the painting was transported to the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles for an in-depth study and conservation treatment. GCI conservators first removed the aged varnish on the surface, which restored the original brilliance and depth of color. They also built a new stretcher to accommodate the slightly curved canvas. Additionally, the Getty Conservation Institute’s scientific analysis revealed several important discoveries regarding Pollock’s process and methods.

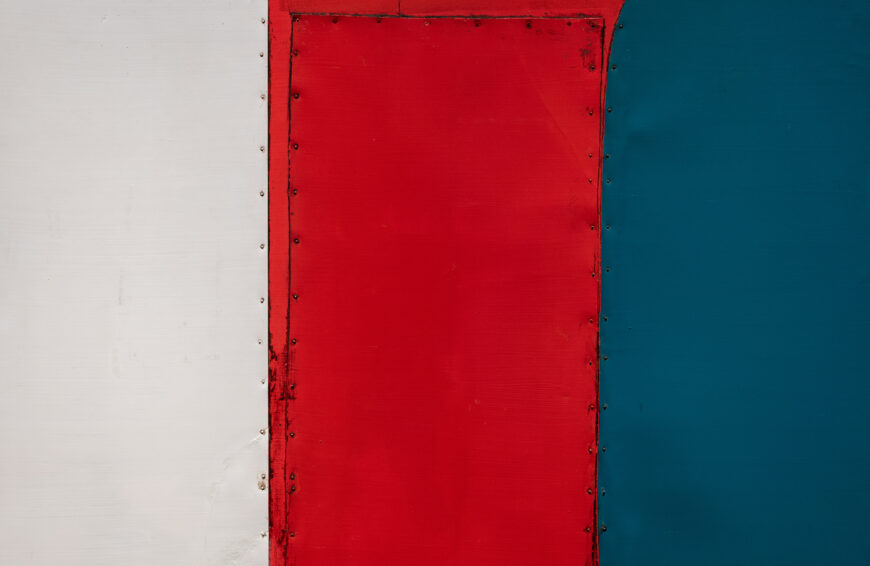

Jackson Pollock, Mural, 1943, oil and water-based paint on linen, 242.9 x 603.9 cm (University of Iowa Museum of Art)

Technique

A number of myths surrounding the creation of this painting were debunked by GCI conservators. First among them is the idea that Mural was completed in a single night, in a sudden burst of inspired creativity. Instead, careful analysis of the canvas unmistakably revealed multiple layers of dried paint. All but one of the colors used in Mural were traditional oil paint, which takes days or even weeks to dry. If an artist were to apply paint over a layer of still wet paint, there would be a distinct blending or swirl of colors. Several areas of this canvas reveal this blending, but many other areas do not, indicating a much longer timeframe than a single night.

Jackson Pollock, Mural (detail), 1943, oil and water-based paint on linen, 242.9 x 603.9 cm (University of Iowa Museum of Art)

The only paint to be identified as water-based is off-white, which Pollock may have applied in the final stages of the painting. Its quick-drying nature may have been the reason for its use, although, significantly, this anticipates his later well-known experimentation with house paint. The areas of white provide visual space in between the vibrant curvilinear brushstrokes, as well as unifying the composition as a whole.

Jackson Pollock, Mural (detail), 1943, oil and water-based paint on linen, 242.9 x 603.9 cm (University of Iowa Museum of Art)

Another myth is that Pollock used his signature drip technique, wherein the canvas is placed flat on the studio floor while the artist flicks paint in a seeming haphazard manner. However, the drips are always flowing in the downward direction, indicating that the canvas was standing upright. Additionally, GCI conservators were able to replicate the shape and size of these drips on an upright canvas with a vigorous flick of the wrist. Although Pollock may not have used his “action painting” technique on this canvas, it does point in that direction.

Significance

Why is this painting important and what was Pollock trying to paint? Mural is the largest canvas Pollock ever painted and is often seen by art historians as a moment of liberation as the artist pushes beyond the restrictive traditions of easel painting. Stylistically this marks a moment of transition from his earlier surrealist-inspired biomorphic abstraction to more gestural, more active painting. The pronounced brushwork and occasional drip point to an energetic, rhythmic creative expression that Pollock will explore more fully in the future.

Jackson Pollock standing beside Mural at Vogue Studios © Estate of Herbert Matter (Special Collections and University Archives Department, Stanford University Libraries)

What do you see in Mural? Faces, figures, birds, numbers, letters—all are partly visable, partly hidden within this massive painting. However, given Pollock’s interest in the Surrealist concept of automatism (automatic actions, used to express the creative force of the unconscious), as well as Jungian concepts such as the collective unconscious, he may well have been interested in opening the viewer’s mind to universal archetypes. What can be seen inside Mural? The answer may provide more insight into viewer as an individual, than a simple decoding of the artist’s brushstrokes.