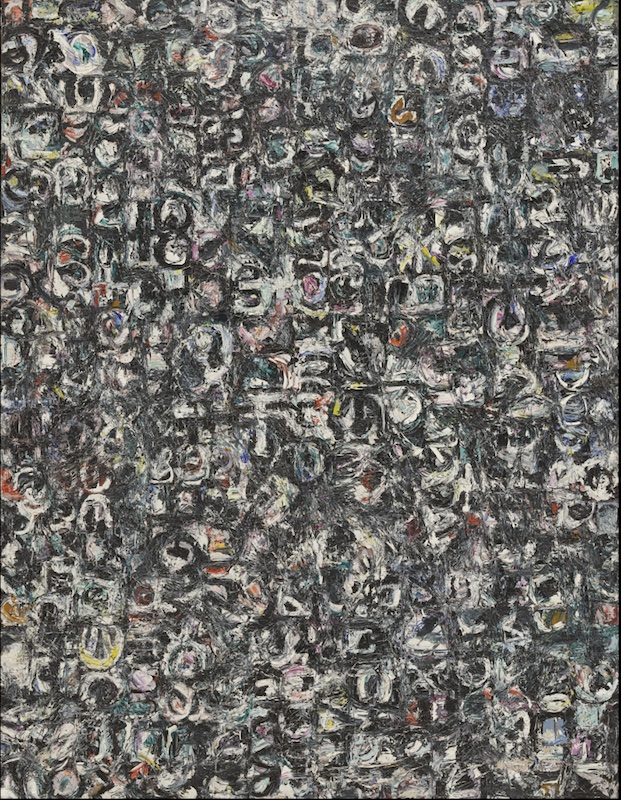

Lee Krasner, Untitled, 1949, oil on composition board, 121.9 x 93.9 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Little images

By the standards of the New York School (an umbrella term for post-World-War II American abstract artists), Untitled is a relatively small work—vertically oriented and consisting of tightly painted, gridded crescents of black and white paint with flecks of vibrant color, it measures 48 x 37 inches. This painting belongs to a series from the late 1940s that Krasner called “Little Images.” An ironic title, no doubt, when one considers how large and heroic were the paintings of that period’s leading figures like Jackson Pollock (whom Krasner married in 1945), Willem de Kooning, and Barnett Newman.

Figures in front of Jackson Pollock, One: Number 31, 1950, 1950, oil and enamel paint on canvas, 269.5 x 530.8 cm (MoMA)(photo: Devyn Caldwell, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Painting large meant that one worked with large—almost comically so—brushes and the resulting meshes of abstract form and color encapsulated this muscular new approach to art. Pollock’s method of laying out large sheets of canvas upon the floor or Barnett Newman’s use of broomstick-length brushes stands in marked contrast to Krasner’s approach—hers were done on a tabletop. Thus, the tightly woven and interlocking shapes of Untitled had little of the drip and sweep of Pollock or de Kooning. Were the “Little Images” a breakthrough as she would later state—the beginnings of a feminist commentary on the part of Krasner? She would, after all, incorporate strips of Pollock’s discarded canvases into a mid-50s’ collage series, an act that art historian David Hopkins described as a “muting of [Pollock’s] painterly heroics.” Her name has in fact became virtually synonymous with the topic of “women and art,” despite the fact that on its face at least, abstract painting has nothing to do with gender.

Women generally not invited

The reason for this has a lot to do with how we now understand this period in art history. Women artists faced inordinate obstacles. There was a machismo that characterized the painters and sculptors who frequented the famous Cedar Tavern and took part in “The Club,” the organization that Phillip Pavia founded in 1948 and that served as an informal meeting space for members. Women were generally not invited. Despite her centrality to the New York School and her friendship with many leading figures in the New York art world of the 1940s and 50s, it would take a number of years for Krasner to receive the kind of attention Pollock seemed to warrant almost immediately. Is this why the artist adopted the name “Lee Krasner” instead of her birth name Lena Kreisner? Lee was suitably ambiguous in terms of gender. Krasner would sometimes just sign her paintings with the initials “L.K.” or otherwise diminish her signature. In Ann Eden Gibson’s study of this period, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics, the author suggests that the “anonymity made possible by the gallery system—the dealer was visible but the artist was not—provided female artists with the chance to pass as men.”

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in front of his work, c. 1950 (photo: Archives of American Art)

The influence of Cubism and Surrealism

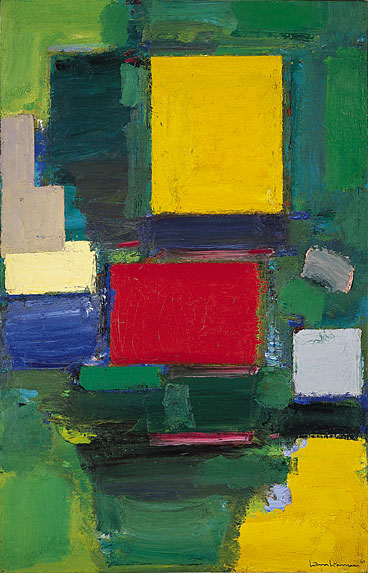

Hans Hofmann, The Gate, 1959-60, oil on canvas, 190.5 x 123.2 cm (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum)

The notion that work of women artists could achieve a universal significance was often dismissed. “Little Images” nevertheless issued from the same set of pictorial concerns faced by her male counterparts. Grappling with the legacies of Cubism and Surrealism in the post-war years, American artists pushed through to dramatically new configurations of abstraction.

Untitled shows the influence of Cubism’s radical reordering of Renaissance perspective. The space of the painting is shallow; the overall palette is black and white. Krasner had studied with the German expatriate Hans Hoffman in the 1930s whose influence on the post-world II generation of artists cannot be over-stated (see image, left). Hoffman advocated a “push-pull” approach to painting (which emphasized both the flatness of the painting’s surface and the creation of abstract forms that could move forward and back into space) and took its cues from Cubist geometry.

The work in the series “Little Images” represents a break from the over-arching influence of Cubist art whose geometric forms were still rooted in the study of nature. In the postwar years this “hard-edged” approach was softened by the influence of the organic abstraction of surrealist artists, many of them living in New York (see Gorky’s Diary of a Seducer, below for an example).

Surrealism represented an art of the unconscious mind; it seemed perfectly suitable to the unreality of the war years and after when artists started to grapple with the possibility or impossibility of representing the war’s aftermath. Krasner described her interest in Surrealism emerging around 1945 as a result of the large emigrant population of European Surrealists in New York City. But surrealism, like Cubism was still rooted in the observation of nature—however distorted. When Krasner first met Pollock she saw that, instead of abstracting his forms from nature, he began with a blank canvas upon which he would begin to arrange skeins of color in the all-over technique for which he became famous. Abandoning nature as a source for art allowed for greater freedom of choice.

Arshile Gorky, Diary of a Seducer, 1945, oil on canvas, 126.7 x 157.5 cm (MoMA)

Nature is not the source

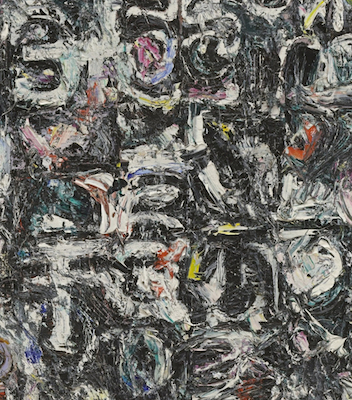

Abstracted marks (detail), Lee Krasner, Untitled, 1949, oil on composition board, 121.9 x 93.9 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

But if nature is no longer a source for artists, then what is? In the postwar years the focus shifted to myth or inward to a deeply personal realm. Krasner’s painting appears hieroglyphic—as if the artist were repeatedly tracing numbers or letters over and over again across the surface. Her painting may be based on Hebrew letters from her childhood studies but dissembled in such a way that Untitled seems akin to the Cold War scrambling of codes. The personal was often connected to larger historical realities. Krasner’s abstract rendition of Hebrew could thus be read as a reference to the Holocaust, which represented for many the almost unimaginable horror, along with the Atom bomb, of contemporary life in the 1950s.

But if art historians now read these works of art within larger critical and historical frameworks, it is important to remember that artists of the postwar period resisted such interpretations. They stressed instead private symbolism. Artists sought to sever the link between the work of art and the everyday world. The post-war art critic Clement Greenberg, whose name is synonymous with the term “formalism,” advocated a non-representational approach to art. For Krasner, well versed in advanced theories of art, “Little Images” represented a breakthrough into this new realm, a post-Cubist and post-Surrealist abstraction. The one reality she could never escape was the fate bestowed upon women artists in an era dominated by the heroic male.