This furry tea service was a touchstone for Surrealism, but the artist was a victim of her own success.

Meret Oppenheim, Object, 1936, fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, cup 4–3/8 inches in diameter; saucer 9–3/8 inches in diameter; spoon 8 inches long, overall height 2–7/8 inches (The Museum of Modern Art, New York). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:00] The artist Meret Oppenheim was sitting in a café in Paris in 1936 with Picasso and Dora Maar.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:11] They were admiring a bracelet that Oppenheim was wearing, that she herself had made, which was metal wrapped in fur, and Picasso remarked, “You could cover anything with fur.”

Dr. Zucker: [0:22] And Oppenheim said, “Even this cup and saucer,” and soon after, she purchased some Chinese gazelle and wrapped a cup and saucer and spoon, which is what we’re seeing here. This object became very famous very quickly, and cuts to the heart of the Surrealist strategy of the collision of things that don’t belong together in order to rupture our sense of normalcy.

Dr. Harris: [0:43] Oppenheim was a serious Surrealist artist. She was engaged with the Surrealists in Paris at a very young age, and felt very strongly about the independence, of the freedom, of the artist, and how difficult those things were as a woman artist.

[1:05] So although that famous story about this object is a fun one to tell, it does center it around Picasso and could lead us to forget about the importance of Meret Oppenheim herself.

Dr. Zucker: [1:18] The artist was keenly aware that she was too often viewed as a muse and as a companion, but Oppenheim was forceful in her assertion of her own artistic independence.

Dr. Harris: [1:23] I do wonder whether Picasso or a male member of the Surrealist group would have adopted domestic objects like this and have done something so creative and unusual.

Dr. Zucker: [1:32] The teacup and saucer and spoon was associated with the domestic, with the feminine, as is fur, but there is this striking and aggressive relationship between the cool, crisp, smooth, hard quality of the porcelain and the tactile quality of the fur.

Dr. Harris: [1:55] You describe the fur as being feminine, and we could associate the fur with a fur coat, for example. But the fur also, for me, represents the wild and the uncivilized, these things that are so elemental, as opposed to the polite society in which we usually think of the teacup and saucer and teaspoon.

[0:00] So there’s a kind of brutality and even violence here, to me.

Dr. Zucker: [2:15] The idea of wet, warm, fur touching your tongue, touching your lips, liquid pouring across that fur into your mouth, is immediately repellent, but it’s interesting to think about why it’s repellent. To think about it through a psychoanalytic lens, and psychoanalysis was of deep interest to the Surrealist community.

[2:34] That while our conscious mind, our civilized mind, our public mind, is repelled by this, at a deeper level, our unconscious mind is attracted to it, that there’s a degree of desire that we have to keep hidden.

[2:59] The conflict between the unconscious and the conscious is what makes us so deeply uncomfortable. That is a conflict that has been so much a part of modern culture in the 19th and 20th centuries.

[3:05] I think the brilliance of the object is its ability to bring to the fore this collision between polite society and the rawness of interior self.

[0:00] [music]

A luncheon with fur

The story behind the creation of Object, an ordinary cup, spoon, and saucer wrapped evocatively in gazelle fur, has been told so many times its importance in modernist history transcends the fact it might be apocryphal (of dubious authenticity). The twenty-two year old Basel-born artist, Meret Oppenheim, had been in Paris for four years when, one day, she was at a café with Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar. Oppenheim was wearing a brass bracelet covered in fur when Picasso and Maar, who were admiring it, proclaimed, “Almost anything can be covered in fur!” As Oppenheim’s tea grew cold, she jokingly asked the waiter for “more fur.” Inspiration struck—Oppenheim is said to have gone straight from the café to a store where she purchased the cup, saucer, and spoon used in this piece. This amusing story belies the importance of Object and the critical acclaim and public fascination that has elevated it to point where it has become the definitive surrealist object…ultimately to Oppenheim’s dismay.

Cup detail, Meret Oppenheim, Object, 1936, fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, cup 4–3/8″ in diameter; saucer 9–3/8″ in diameter; spoon 8″ long, overall height 2–7/8″ (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What is a Surrealist object?

Oppenheim’s Object was created at a moment when sculpted objects and assemblages had become prominent features of Surrealist art practice. In 1937, British art critic Herbert Read emphasized that all Surrealist objects were representative of an idea and Salvador Dalí described some of them as “objects with symbolic function.” In other words, how might an otherwise typical, functional object be modified so it represents something deeply personal and poetic? How might it, in Freudian terms, resonate as a sublimation of internal desire and aspiration? Such physical manifestations of our internal psyches were indicative of a surreality, or the point in which external and internal realities united, as described by André Breton (one of Surrealism’s founders and theorists) in his first Manifesto of Surrealism.

Spoon detail, Meret Oppenheim, Object, 1936, fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, cup 4–3/8″ in diameter; saucer 9–3/8″ in diameter; spoon 8″ long, overall height 2–7/8″ (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Visceral responses

What, then, do we make of this set of be-furred tableware? Interpretations vary wildly. The art historian Whitney Chadwick has described it as linked to the Surrealist’s love of alchemical transformation by turning cool, smooth ceramic and metal into something warm and bristley, while many scholars have noted the fetishistic qualities of the fur-lined set—as the fur imbues these functional, hand-held objects with sexual connotations.

In a 1936 issue of the New Yorker Magazine, it was reported that a woman fainted “right in front of the fur-bearing cup and saucer [while it was on exhibit at MoMA]. “She left no name with the attendants who revived her – only a vague feeling of apprehension.”1 Such visceral reactions to Oppenheim’s sculpture come closest, perhaps, to what were likely the artist’s aspirations. In an interview later in life, Oppenheim described her creations as “not an illustration of an idea, but the thing itself.”

Unlike Read and Dalí, Oppenheim stresses the physicality of Object, reinforcing the way we can readily imagine the feeling of the fur while drinking from the cup, and using the saucer and spoon. The frisson we experience when china is unexpectedly wrapped in fur is based on our familiarity with both, and the fur requires us to extend our sensory experiences to fully appreciate the work. Object insists we imagine what sipping warm tea from this cup feels like, how the bristles would feel upon our lips. With Oppenheim’s elegant creation, how we understand those visceral memories, how we create metaphors and symbols out of this act of tactile extension, is entirely open to interpretation by each individual, which is, in many ways, the whole point of Surrealism itself.

Meret Oppenheim, Object, 1936, fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, cup 4–3/8″ in diameter; saucer 9–3/8″ in diameter; spoon 8″ long, overall height 2–7/8″ (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Presentation problems

In spite of our individual response, the interpretation of Object has been complicated by the ways it was assigned meaning by others. When Object was finished, Oppenheim submitted it to Breton for an exhibition of Surrealist objects at the Charles Ratton Gallery in Paris in 1936. However, while Oppenheim preferred a non-descriptive title, Breton took the liberty of titling the piece Le Déjeneur en fourrure, or Luncheon in Fur. This title is a play on two nineteenth-century works: Édouard Manet’s infamous modernist painting Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeneur sur l’herbe) and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s erotic novel Venus in Furs. With these two references, Breton forces an explicit sexualized meaning onto Object. Recall that the original inspiration for this work was implicitly practical: when Oppenheim asked the waiter for more fur for her cooling teacup, it was suggested as a way to keep her tea warm, and not necessarily as overtly sexual.

Meret Oppenheim, Das Paar (The Couple), pair of brown shoes attached at the toes, original version 1936, remade 1956

The meaning of others

Certainly we cannot assume that the spark of the idea for this piece and the piece itself are necessarily related, but the way meanings have been ascribed to Oppenheim’s pieces by others has plagued many of her works.

Art historian Edward Powers has noted that when Oppenheim sent her Surrealist object Das Paar to a photographer before submitting it for exhibition, the photographer took the liberty of tying up the laces before photographing it. When Breton saw the photo with tied laces, he dubbed this object à délacer which in French means to untie, typically either shoes or a corset. The title and laced shoes together suggest the potential act of undressing and a fascination with exposing the female body. However, when Oppenheim later described Das Paar (with the laces untied), she stated it was an “odd unisexual pair: two shoes, unobserved at night, doing ‘forbidden’ things.” She expressly assigned no gender, and suggests the “forbidden” acts already taking place between anthropomorphized shoes. She takes a more literal approach, the shoes as expressive things in themselves, rather than symbolically resonant of something else.

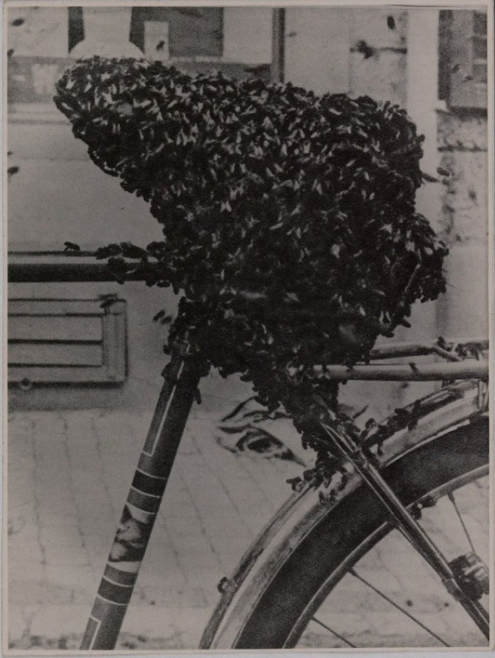

This is not to suggest that all her interactions with Breton were negative. When she happened across a wonderfully disturbing photograph of a bicycle seat covered in bees, she mailed it to Breton, who republished the found photograph as an artistic contribution by Oppenheim in the third issue of the new Surrealist publication Medium.

Meret Oppenheim, Object, 1936, fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, cup 4–3/8″ in diameter; saucer 9–3/8″ in diameter; spoon 8″ long, overall height 2–7/8″ (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Dangerous success

Yet, the early acclaim for the fur-covered Object had a negative effect on Oppenheim’s early career. When it was purchased by The Museum of Modern Art and featured in their influential 1936–37 exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism,” visitors declared it the “quintessential” Surrealist object. And that is how it has been seen ever since. But for Oppenheim, the prestige and focus on this one object proved too much, and she spent more than a decade out of the artistic limelight, destroying much of the work she produced during that period. It was only later when she re-emerged, and began publicly showing new paintings and objects with renewed vigor and confidence, that she began reclaiming some of the intent of her work. When she was given an award for her work by the City of Basel, she touched upon this in her acceptance speech: “I think it is the duty of a woman to lead a life that expresses her disbelief in the validity of the taboos that have been imposed upon her kind for thousands of years. Nobody will give you freedom; you have to take it.”