Robert Rauschenberg, Retroactive I, 1963, oil and silkscreen-ink print on canvas, 213.4 x 152.4 cm (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art) All works © Robert Rauschenberg

[0:00] [music]

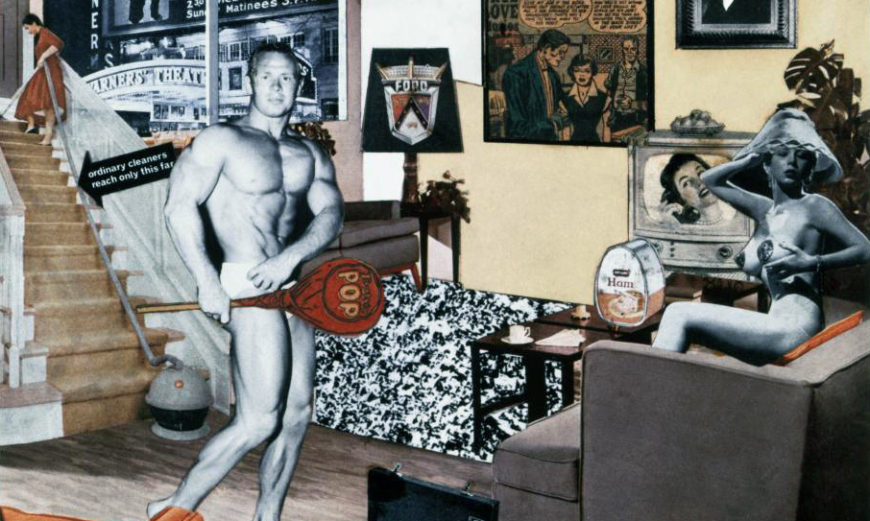

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, looking at a large painting by Robert Rauschenberg. This is “Retroactive I,” from 1963.

Patricia Hickson: [0:15] “Retroactive I” was made immediately following John F. Kennedy’s assassination. We’re looking at a president who was deeply loved by the public, who was recently assassinated, and here pictured as the central element of a painting that speaks very emotionally to the times.

Dr. Zucker: [0:32] So the artist has taken a photograph from popular media and blown it up, and then applied it to the surface of this canvas as if it was an oil painting.

Patricia: [0:41] There are multiple screened images on this. All of them taken from popular culture, many from magazines, such as “National Geographic” and “LIFE” magazine. Each image is screened on separately and done in a different color, so there’s a whole brickwork of images that puts together this composition.

Dr. Zucker: [0:58] It must have been so difficult for the artist, who had ordered the screens before the assassination, intending to use this image, but then having the meaning of that image utterly transformed by the time he received it back from the fabricator because of the assassination that had subsequently taken place.

Patricia: [1:14] He had ordered these silk screens. They were in his studio. He was on a trip in the South when he learned of Kennedy’s death and suddenly questioned whether it would be appropriate to really go forward with making these paintings with Kennedy as an element, because Kennedy as a president, and now an assassinated president, has taken on this whole other dimension.

[1:36] The portrait of Kennedy has been sourced from a news conference. It’s a very large image of Kennedy doing this emphatic gesture. This gesture is so connected with Kennedy that his hand is shown twice.

Dr. Zucker: [1:51] The artist would take the image and would send out to a commercial silk screen manufacturer for the screen itself, and then he would take a squeegee, take silk screen ink, and force it through the screen to apply it to the canvas.

Patricia: [2:05] You have to think of these images of being in magazines and newspapers, and so when the artist orders these silk screens that are made by a fabricator, he’s having them blown up, so that they have a much larger presence. So, what was probably a very small picture of navel oranges in a crate is now one by one-and-a-half feet in size, so larger than life.

Dr. Zucker: [2:28] This issue itself is so complicated, because for the entire history of art in the West, we think about the handicraft of making. We think about the skill of one’s brushwork, but here we have a mechanism, a mechanical process, and to complicate it even more, by the time we get to 1963 when this is being produced, contemporary art was supposed to be abstract, and here we have the reintroduction of images.

Patricia: [2:51] Artists like Rauschenberg were reacting against Abstract Expressionist artists, but at the same time, there are many elements that show the artist’s hand. You see brushwork, you see drips, so it’s not pristine reproduction.

Dr. Zucker: [3:05] So there’s a reference to the drips of Jackson Pollock, to the energized brush strokes of Willem de Kooning. For me, when I’m looking at this image, I’m not seeing Kennedy. I’m seeing an image of Kennedy. This is very much about reproduction and representation.

Patricia: [3:20] We’re looking at a conglomeration of images. Kennedy, of course, is a central element, but then there’s a crate of oranges, there’s a glass of water, there’s a construction site, and there’s an astronaut. It’s a cluster of a lot of different imagery, and it’s as much about what’s going on in the world at the time and about what’s outside your window.

[3:41] In fact, Rauschenberg was quite famous for a particular quote. “I want my paintings to look like what’s going on outside my window, rather than what’s inside my studio,” which is a big change from what, say, the Abstract Expressionists were doing.

Dr. Zucker: [3:54] So where Pollock and de Kooning were trying to make manifest what was taking place in an interior space, within them in some psychological, spiritual way, we have an interest in the mundane, in the immediate, in the actual world that surrounds, in the events around us, the debris of news, the debris of our commercial and industrial culture.

Patricia: [4:16] Think about Rauschenberg with his studio in downtown New York, and outside his window, probably plenty of construction sites, markets that sold cartons of oranges. These things were just outside his window, like he says in the quote.

Dr. Zucker: [4:30] Kennedy, who is front and center, is surrounded, is framed by all of these other forms. We have a thermometer, or at least a forecasting device. We have photographs of a nude through space, through time, the glass of water, all of these things framing the central figure.

Patricia: [4:46] Kennedy was very closely associated with the space race with Russia. So to have Kennedy front and center, and then to have an astronaut, the second largest image over his shoulder, I think it’s really speaking a lot to Kennedy directly as well as the generalities of what’s going on out in the world.

Dr. Zucker: [5:01] Kennedy had made this promise that we’re going to go to the moon, and although we didn’t in his lifetime, there was a tremendous technological set of advances that were unleashed as a result. Rauschenberg was a real fan of the American space program, of science and technology more generally.

Patricia: [5:16] Kennedy was a very popular president, and Rauschenberg, too, was very much engaged with Kennedy. I think he was devastated when Kennedy was assassinated, and his work became much more political after that.

Dr. Zucker: [5:28] Even though this painting is so concerned with the contemporary, because the painting was made after Kennedy’s death, it becomes a memorial.

Patricia: [5:37] Kennedy is eternally young. He’s depicted exactly how all of us remember him and see him in history books. It really is just an incredible homage to a very important political figure.

[5:49] This is the only painting from the Kennedy works, of which there are eight, that depicts Kennedy in blue. Most of the others show him in black and white or even real color. And so this is very strong in a way that it conveys the impact of this tragedy and is taking on this kind of ghostly visage.

[6:09] [music]