Unlike the other monuments on the Mall, this monument tells us virtually nothing about the man it commemorates.

The Washington Monument, Washington, D.C., Robert Mills architect, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas L. Casey engineer, completed 1884, granite and marble, 169 m high. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

0:00:06.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: We’re standing at the base of the Washington Monument in the middle of Washington, D.C. This is one of the great icons of the United States.

0:00:15.8 Dr. Beth Harris: And the monument is on a bit of a hill. And if we look in one direction, we see the Capitol Building, and in the other direction, a monument to another president: we see the Lincoln Memorial in front of a beautiful reflecting pool.

0:00:27.9 Dr. Steven Zucker: And then perpendicular is the White House. This is a celebration of the great founding father of the United States, George Washington, at the intersection of the legislature and of the White House—that is the power of the presidency and the power of the Congress.

0:00:41.9 Dr. Beth Harris: This is a city that is planned to speak to the ideals of the Republic of the United States. And so the Washington Monument was planned, even while Washington himself was alive, and took almost 100 years after his death to be completed.

0:01:00.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: The first monument that was envisioned was one that celebrated Washington on horseback, an equestrian sculpture. And this is a tradition that had been used to represent kings, but it actually went all the way back to Ancient Rome to the celebration of Ancient Roman emperors. But while that tradition has been represented in sculptures in New York, in Richmond, Virginia, and in Baltimore, we’re standing before something that is of an entirely different scale.

0:01:26.6 Dr. Beth Harris: It’s a little odd when we think about it in the context of D.C., where we have these memorials to Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln that are more of what I expect of a way of remembering a great hero of the United States. We see their likeness. We see it in the context of an ancient classical temple which reminds us of the ancient Roman Republic.

0:01:50.3 Dr. Steven Zucker: We don’t see anything else in Washington, D.C. that looks just like this. This is so singular.

0:01:56.4 Dr. Beth Harris: And maybe that’s because we think about Washington as singular, as the first president, as a man who was very much idealized.

0:02:05.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: So what do we make of the abstraction of this form? Well, I think what’s critical to understand is that this is, in fact, drawn from antiquity, but it’s not the antiquity of Ancient Greece. It’s not the antiquity of Ancient Rome. This is drawn from Ancient Egyptian structures.

0:02:20.4 Dr. Beth Harris: These were often set up as pairs in front of Egyptian temples, and we refer to them as obelisks. Obelisks have a long history, not just in Ancient Egypt, but they were actually moved by Roman emperors from Egypt to Rome, because they were seen as symbols of power and authority. And if we think about the obelisk as a symbol of imperial authority in Ancient Rome, it’s a far cry from the ideals of George Washington and from the ideals of a young republic, notions of self-governance, of power being in the hands of the people, and not an autocrat.

0:02:57.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: Which is actually why it took so long to decide what to build here. It was clear that the country wanted to honor George Washington. The big problem was what would that memorial look like?

0:03:10.0 Dr. Beth Harris: And so this first idea of an equestrian sculpture, that idea didn’t go very far. And then when Washington dies, there was a unanimous resolution for a public tomb right in this location, even though Washington himself specified that he wanted to be buried in his home in Mount Vernon.

0:03:29.3 Dr. Steven Zucker: That outdoor tomb was intended to take an Ancient Egyptian form as a stepped pyramid. The real problem was that there were two divergent political theories in the United States in these early years. There were, on the one hand, the Republicans, who thought power should be vested in the people, that government should be minimized as much as possible, and that we should be a largely self-governing populace.

0:03:52.2 Dr. Steven Zucker: On the other side of the aisle were the Federalists, who believed that there should be a strong central government, that national infrastructure, taxes, and other levers of governance would be important to the new republic. And it’s so interesting that this basic division informed the arguments for and against a grand monument to George Washington.

0:04:11.0 Dr. Beth Harris: There was actually a vote along party lines about the proposed monument in the form of the stepped pyramid, with the Federalists voting for it and the Republicans voting against it, feeling that it was too ostentatious, that it was essentially a monument that would demonstrate the worship of a man who was singular and extraordinary, instead of being one of the people, of the citizenry.

0:04:35.3 Dr. Steven Zucker: And so the memory of George Washington, this man that both sides agreed was the ideal symbol of the new nation, became this central point of political contention. But despite these differences, some practical progress was made.

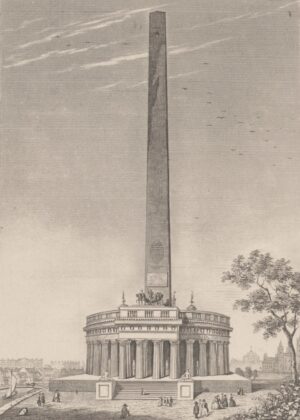

0:04:48.4 Dr. Beth Harris: In 1833, the Washington National Monument Society, a private organization, was founded to support the building of the monument. And at that point, the idea for the design had evolved into a temple crowned by an obelisk.

0:05:05.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: It’s such an architectural mishmash, because on the one hand, the temple is in the Ancient Greek and Roman style, but the obelisk is Egyptian. And it’s such a perfect example of the ways in which the 19th century looted history for precedence that spoke to grandeur, but also to, for them, I think, a kind of historical authenticity. Some progress was started with the building of the obelisk itself, although fundraising was slow and then finally ground to a halt when a group called the Know Nothings seized control of this private society that was meant to fund and build the obelisk. Now, the Know Nothings were an extreme political group that wanted to keep immigrants out of the United States.

0:05:44.4 Dr. Beth Harris: And there was lots of criticism at the time of the design itself. Someone referred to it as “a broomstick and a handle.” And so there was really no agreement yet, even though it had been begun, about what the final version would really be like.

0:06:00.2 Dr. Steven Zucker: Needless to say, nothing was done during the Civil War. And I think for many, the unfinished stub of a building became a symbol of the failure of the United States.

0:06:08.4 Dr. Beth Harris: So in 1876, Congress resolves to finish the monument. So this becomes, once again, a publicly-funded project. Congress asks for designs, and all sorts of things were offered, including memorials in the style of the medieval gothic, of the Italian Renaissance, designs that were a mishmash of different historical styles.

0:06:33.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: As we enter the last quarter of the 19th century, the real hero of the story is Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Casey of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He takes over the project, but he is very careful to say that he’s not creating an architectural design. He is simply an engineer moving the project forward.

0:06:51.3 Dr. Beth Harris: Perhaps in the end, what the monument speaks to is a country that was aggressively expanding westward, increasingly wealthy, technologically sophisticated.

0:07:04.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: Some historians have said that it was only possible for Congress to act in 1876 in the wake of the Civil War, because the age of George Washington had receded enough that the old arguments between the Federalists and the Republicans had been replaced by new realities.

0:07:21.0 Dr. Beth Harris: What was the language one could use in the modern world to speak to these transcendent values?

View of the National Mall showing the Washington Monument in the center. Robert Mills and Lietenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey, Washington Monument, completed 1884, granite and marble, Washington, D.C.

Robert Mills and Lietenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey, Washington Monument, completed 1884, granite and marble, Washington, D.C. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Evolving American narratives

At 555 feet high the Washington Monument towers over the National Mall. In a city of height-restricted buildings, this enormous, mottled-marble obelisk can be seen piercing the sky from miles around like a beacon to the country’s symbolic center. Once there, the observation deck at the top of the monument provides visitors with a breathtaking bird’s eye view of the city—from the World War II Memorial, past the Lincoln Memorial and over Arlington Bridge to the west, down the museum-lined Mall to the Capitol Building to the east, over the Ellipse and past the White House to the north, and beyond the Tidal Basin and the Jefferson Memorial into Virginia to the south. Built to honor the country’s first president, the Washington Monument is the linchpin of an evolving American narrative told through the buildings and monuments that surround it.

L’Enfant’s proposal

Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the architect and city planner responsible for the design of Washington D.C. and the National Mall, was the first to propose a monument to Washington. Inspired by the city planning in his native France, L’Enfant suggested placing an equestrian statue of George Washington as commander of the Continental Army in the middle of the National Mall. It was to be set on the spot where the sight lines from the White House and the Capitol intersected so that future presidents and members of Congress would always have Washington in view and on their minds as they deliberated on what was best for the country. Funding fell short for L’Enfants’ grand scheme, however, and his sculpture was never completed.

Mills’ proposal

54 years later, Federal architect Robert Mills put forward plans to celebrate Washington with a 600 foot tall Egyptian-style obelisk surrounded by a vast colonnade decorated with sculptural elements recalling ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome. Unlike a true Egyptian obelisk which was carved from a single block of stone, the one Mills proposed would be made of many marble blocks some carved with portraits of the first president in action. Its grandeur would serve to equate George Washington with the greatest leaders of antiquity.

With a modest amount of private funding in hand, Mills began work on the obelisk thinking he would be able to raise the rest. However, the venture did not go as planned. By 1851, the marble shaft of the obelisk was only one-quarter complete. It stuck up like a great stump and became a symbol for the government’s poor planning and mismanagement of the Mall.

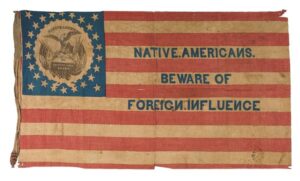

A flag representing the ideas of the Know-Nothing Party, originating in 1849 and active throughout the 1850s.

Money problems

The Monument’s Board of Managers lobbied Congress for money but was soon overthrown by a group of anti-immigration, anti-Catholic activists called the “Know-Nothings”. The Know-Nothings wanted to use the monument to promote their “America for Americans” agenda by having the monument paid for and built by those who supported their cause. However, the oncoming Civil War drained interest from the project and the Washington Monument remained stump-like for more than a quarter century. Then, in 1878, Congress appointed Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey, an army engineer, to complete the project.

Colonel Casey

Colonel Casey jumped into the project by significantly altering Mills’ plans. Right away he simplified the design of the obelisk, stripping the structure of extraneous decoration, and creating a narrower, higher, peak at the top. Using a white marble that was a better quality, but not an exact match of the first stone used, Casey completed the monument. And while Congress gave Casey money incrementally and tried to intercede in the design process, they failed to get the Colonel to alter his vision of a façade free of any and all ornamentation. In 1884, over widespread objections about its lack of descriptive, narrative and historical elements, Casey completed the memorial.

Robert Mills and Lietenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey, Washington Monument, completed 1884, granite and marble, Washington, D.C. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the end, it had taken more than three dozen years for the Washington Monument to be completed. Soil stability issues forced its move some 400 feet from the exact intersection point for the Capitol and White House. Funding shortages, politics and the intrusion of the Civil War delayed its completion.

But what does it actually tell us about Washington? Unlike the other monuments on the Mall, the Washington Monument says next to nothing about the subject for whom it was created. In contrast, one can learn a lot about Lincoln from visiting the Lincoln Memorial, viewing his sculptural likeness and reading his words inscribed on the walls. And a person can learn a lot about World War II by visiting that Memorial and studying the reliefs, inscriptions, sculptures and other symbolic features. But one cannot learn anything about the way Washington looked or his words or deeds by visiting the Washington Monument. And that is a result of the long and contentious process from which the Monument to America’s first president arose.

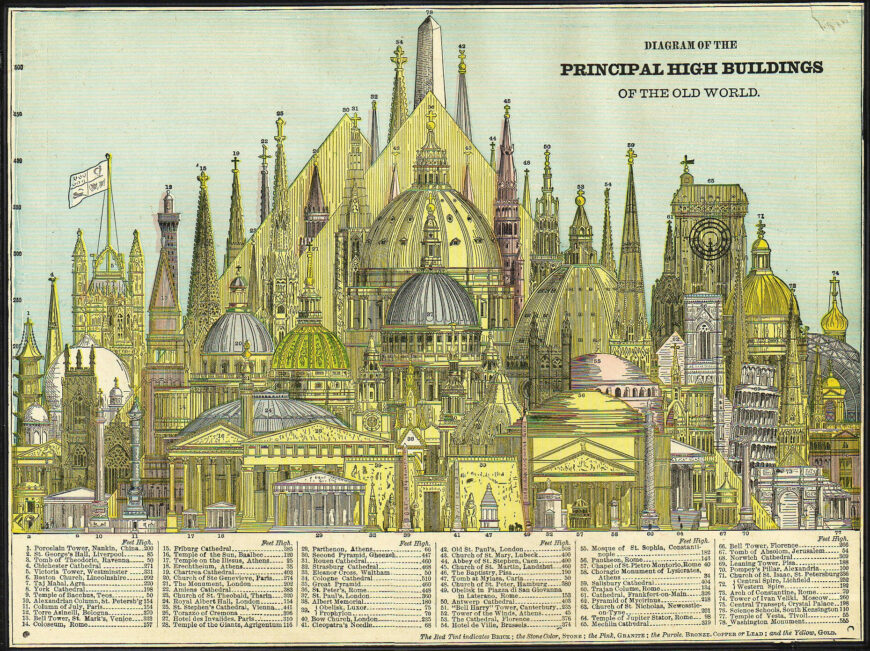

Diagram of the principle high buildings of the old world, showing the Washington Monument to be the tallest, 1884, lithograph color print

The Washington Monument receives an estimated 4 million visitors a year. It was the tallest building in the world until the completion of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, and remains the tallest stone building in the world today.