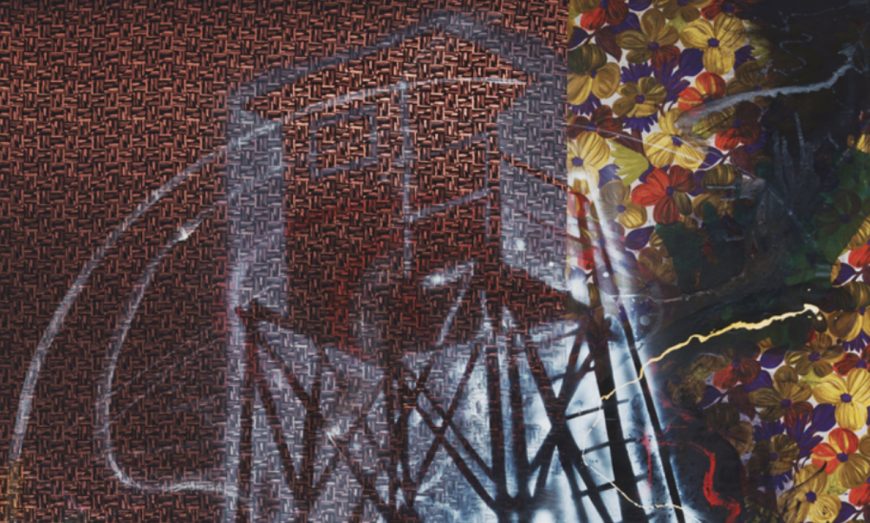

An abstract painting, a collage, three musicians, two guitars and a banjo.

Romare Bearden, Three Folk Musicians, 1967, collage of various papers with paint and graphite on canvas, 50 x 60 x 1 ½ inches (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond). A conversation with Dr. Sarah Eckhardt, Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Dr. Leo Mazow, Louise B. and J. Harwood Cochrane Curator of American Art, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and Dr. Steven Zucker