Starting in 1912, surprising new elements begin to turn up in works by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque: cut-up pieces of newspaper, wallpaper, construction paper, cloth, and even rope. Although the resulting collages are visually very different from the largely monochromatic oil paintings most commonly associated with the movement, they are still considered to be part of Cubism.

Partly this is because these works often included drawings that use techniques associated with Cubism, such as deconstructing objects into fragmented, angular forms seen from multiple perspectives. Beyond this similarity, though, there is also another, more conceptual one. This new phase of Cubism is also dedicated to exploring the ambiguities of representation, now on an even wider scale.

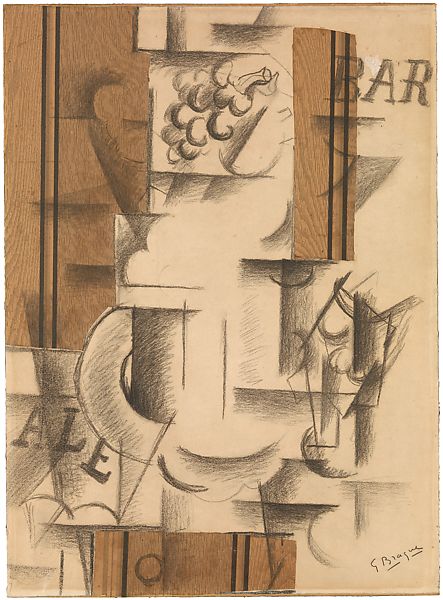

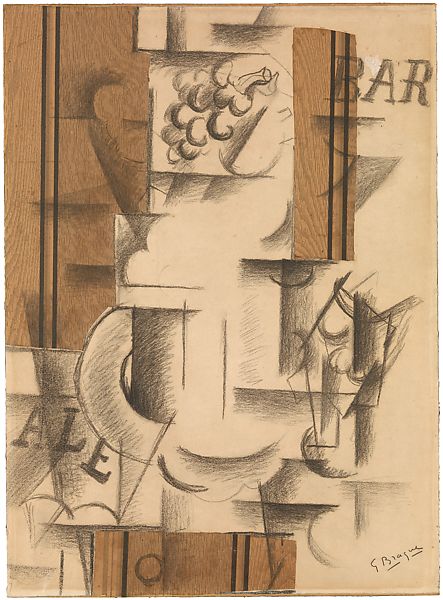

Georges Braque, Fruit Dish and Glass, 1912, charcoal, wallpaper, and gouache on paper, 24 3/4 x 18 inches (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Fruit Dish and Glass is Braque’s first work using papier collé (pasted paper), a subset of collage made using only paper. Picasso’s first collage, Still Life with Chair Caning preceded Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass by a few months and was made from a variety of materials including oilcloth and rope. Papier collé was a central medium in the second phase of Braque’s and Picasso’s joint Cubist investigations commonly known as Synthetic Cubism.

Retreat from abstraction

During this phase both artists retreated from the verge of total abstraction they had reached in their late Analytic Cubist paintings. Synthetic Cubist works use multiple forms of representation, combining the abstracted forms of Analytic Cubism with color, collage, and even sometimes naturalistic representations, to create a complex whole.

In Fruit Dish and Glass, Braque combines Cubist drawing with illusionistic representation, words, and decorative paper printed with a wood grain pattern (faux bois). At the top we see a bunch of grapes drawn relatively naturalistically, with light and shade defining its three-dimensional forms. The remaining still-life objects are depicted in an Analytic Cubist style that deconstructs them into arcs, cylinders, and flat planes representing a fruit dish, plates, and glasses on a table. The words “BAR” and “ALE” are frequently seen on signs and labels in cafés and indicate the general location of the still life.

References to traditional illusionism

Charcoal drawing extends over the strips of wood grain paper that frame and anchor the central forms. The two vertical strips in the upper portion represent wood paneling on a café wall behind the still life, while the horizontal strip below represents a wooden table supporting the dishes and fruit. A circle drawn on the lower strip of wood grain paper suggests the round knob of a drawer pull. This is a reference to illusionistic paintings, which often depict handles and knobs facing the viewer to enhance the sense of the objects being real and within easy reach.

Jean Siméon Chardin, The House of Cards, 1737, oil on canvas. 82.2 x 66 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington)

The naturalistic grapes framed by lines and pasted paper at the top of the work are also a specific reference to the Western tradition of illusionistic representation. A famous story from Ancient Greece describes how the painter Zeuxis was so skilled an artist that birds tried to eat the grapes he painted. Braque centers his drawn grapes as a well-known example of traditional naturalism and then surrounds them with alternative strategies of representation.

Signifying real objects by other means

The Cubist drawings of suggestive geometric forms are, like the words BAR and ALE, a means of referring to or signifying real objects. If we know the language we know what a word signifies; this is true of French and English, and it is (at least theoretically) true of Cubist forms as well. Once we are aware of Cubist conventions for drawing we can recognize that certain relationships of lines and shapes signify fruit, a glass, or a face. The wood grain paper is also a means of signification. The represented texture refers to the physical materials in the scene, providing further information.

Georges Braque, Fruit Dish and Glass, 1912, detail (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In addition, wood grain paper is, like the drawn grapes, an illusion. The naturalistically depicted grapes represent the central achievement of the European fine art tradition. The wood grain paper is, by contrast, a cheap mass-produced item used for decorative purposes. Its presence undermines the exalted value of artistic skill in creating illusionistic representations, and demonstrates another feature of synthetic Cubism: the collapse of distinctions between “high” art and the cheap, ephemeral materials and techniques of mass-produced design.

A kind of certainty

Braque later wrote:

The papiers collés in my drawings have also given me a kind of certainty.Georges Braque, “Thoughts on Painting” (1917)

This is generally understood to mean that they allowed him a way to retreat from the increasingly unmoored abstraction of late Analytic Cubism and anchor his works more solidly in relation to reality. The vaporous spaces and ambiguous forms of Analytic Cubist paintings like The Portuguese are, however, replaced by a different type of ambiguity resulting from the complex and shifting relationships of disparate materials and modes of signification.

Braque’s association of papiers collés with certainty should also be understood in terms of literalism and materiality. Picasso and Braque often employed collage elements as a shortcut means to represent objects. A newspaper in a still life of a café table will be represented by simply gluing newspaper to the picture plane, rather than painstakingly imitating its appearance using paint. Similarly, literal wallpaper is used to represent the presence of wallpaper in the scene, and the actual label is used to show a label on a bottle of wine. This is a form of playful one-upmanship of the Western tradition of naturalistic depiction: the artist now offers reality itself, rather than illusion.

Georges Braque, Fruit Dish and Glass, 1912, charcoal, wallpaper, and gouache on paper, 24 3/4 x 18 inches (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Collage elements also enhance the physical and tactile qualities of the artwork, which increasingly interested both Braque and Picasso. During this period they both also made sculptures and created pronounced surface textures in their paintings by adding sand, sawdust and other grainy materials to paint.

The strips of wood-grain paper in Fruit Dish and Glass confront the viewer with powerful dark shapes, which create a visually strong frame for the more immaterial charcoal drawing on white paper. In addition, the way the drawing continues onto the pasted paper enhances the typically Cubist interest in the tension between literal flatness and represented spatial depth.

Multiple readings

Pablo Picasso, Siphon, Glass, Newspaper and Violin, 1912, paper and charcoal, 18 1/2 x 24 5/8 inches (Moderna Museet, Stockholm)

In Siphon, Glass, Newspaper and Violin, Picasso displays the multiple ways charcoal drawing and papier collé can be used to represent objects. For example, on the left newspaper is cut into the shape of a siphon, while on the right it is used as a surface for drawings of a glass and part of a violin. Its edges also define the left side of the violin’s upper body and neck.

Analytic cubist techniques are used to depict the glass, violin, and top of the siphon from multiple perspectives, while on the far right, paper painted with illusionistic wood grain indicates the violin’s material. In the center the word ‘JOURNAL’ (the French word for newspaper) cut from a newspaper’s masthead represents that object in a particularly direct and literal way. Although we are not offered a coherent visual illusion of the objects in the title, these multiple media and representational strategies combine to give us all of the relevant information.

Pablo Picasso, Siphon, Glass, Newspaper and Violin, 1912, detail (Moderna Museet, Stockholm)

Papier collé and collage not only anchored Cubist forms more firmly as distinct material objects, they also gave the artists a particularly rich means for generating multiple possibilities of meaning through a combination of media, representational strategies, and suggestive shapes and their formal relationships. Collage shapes, materials, colors, and words all contribute to the complex significations that proliferate in Synthetic Cubism.