Left: unrecorded artist, Virgin of Pomata with Saint Nicholas Tolentino and Saint Rose of Lima, 1700–1750, oil on canvas, 66 x 53.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum); right: unrecorded artist, Virgin of Pomata, oil on canvas, 18th century, 152 x 110 cm (Museo Colonial, Bogotá)

Can a religious painting serve as an advertisement? In the 17th and 18th centuries in the Andean region of South America, many paintings were created that all reference a single statue, the Virgin of the Rosary, located in the Church of Santiago in Pomata, a village in the southwest coast of Lake Titicaca (in present day Peru). The church is located in one of the most transited routes of the Andean region, the path between the cities of Cuzco (one of the religious centers of the Viceroyalty of Peru), and Potosí (the location of the largest and most important silver mine in South America during this period).

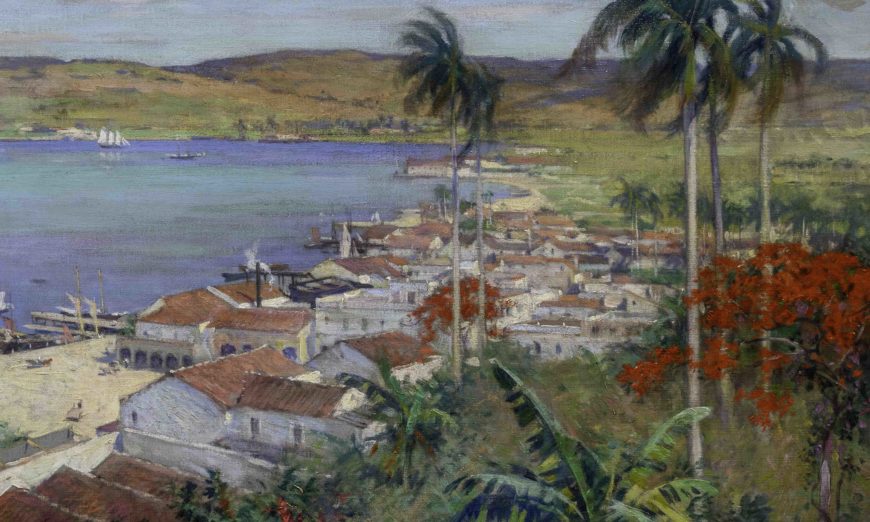

Map showing the location of Cuzco, Potosí, and Pomata, which were all part of the Viceroyalty of Peru (underlying map © Google)

The small town of Pomata was established as one of many along what is now called the “Silver Route” (Ruta de la Plata)—a series of roads that connected the city of Cuzco with the silver mines of Potosí, and then with the ports of the Pacific, where the silver would be transported to Europe. Silver was the main commodity the Spanish Empire was importing from the Andes, and because of that a large influx of people traveled this route.

The statue

The statue was probably taken to the town of Pomata by the Dominican order sometime in the 16th century and was used as an important tool for the founding of Pomata as a religious center, but also as a way of demonstrating the power and control the Dominicans had over the region. The statue is a modest polychrome figure representing the Virgin Mary as the Virgin of the Rosary and was considered miraculous, but there are no clear records of what those miracles were. Venerated until this day, the figure is celebrated in a popular festival annually on the first Sunday of October. [1] The wide distribution of paintings that reference her is a sign of the power of these images, and their distribution was perhaps an indication of gratitude for the miracles the sculpture was understood to perform.

Unrecorded artist, Our Lady of Pomata, c. 1600–1800, oil on canvas, 154.9 x 94 cm (Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth)

The paintings

Paintings referencing the sculpture of the Virgin of the Rosary of Pomata circulated throughout the Viceroyalty of Peru and made this image one of the most popular throughout the Andean region between the 16th and 18th centuries. There are no two paintings alike of the Virgin of Pomata, and they are not faithful copies of the sculpture either. The iconography of the Virgin of Pomata established a unique way of depicting the Virgin—one that combined both Indigenous and European conventions, and that presented individualized versions of the Virgin that allowed for the artists to exercise their creativity within an already established format.

Depiction of a miraculous statue of the Virgin and Child in Wilhelm Gumppenberg, Atlas Marianus Sive De Imaginibus Deiparae Per Orbem Christianum Miraculosis, volume 1 (Ingolstadii: Haenlin, 1657), p. 178 (Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg)

The paintings have different sizes, and each one represents a frontal view of the figure of the Virgin, holding the Christ child in her left arm, with her head slightly tilted towards him. The baby, in most examples, appears holding a sphere representing the world. She holds a rosary, and both Mary and the Christ child wear crowns. This format comes from the European tradition of depicting miraculous statues on their altars, found for example in the 17th-century Atlas Marianus, by the German Jesuit Wilhelm Gumppenberg, with all the corresponding decorations like mantels, plinths, and the specific enhancements that each community will give these miraculous images. In the case of the Virgin of Pomata, this is visible in the rich dresses she and the child wear, as well as the garland of flowers, and the feathers that adorn her crown. These specific elements connect this image with Indigenous traditions of the region.

Feathers and textiles

The two most characteristic elements of the Virgin of Pomata are the colorful feathers in the crowns and the dresses that the figures wear. Both elements connect this image with the Indigenous traditions of the Andes and serve as an anchor to the specific site of Pomata.

Mary and Christ (detail), unrecorded artist, Virgin of Pomata, oil on canvas, 18th century, 152 x 110 cm (Museo Colonial, Bogotá)

Feathers from this relative of the ostrich are thought to be the feathers used in the crowns represented in the paintings of the Virgin of Pomata. Juvenile Suri (Rhea pennata tarapacencis) (photo: Inao, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The feathers that both figures wear are thought to be Suri feathers, a type of ostrich that lives in the Andean highlands, between present day Peru, Bolivia, and Chile, the area where Pomata is located. These feathers were used by Indigenous groups in their rituals and celebrations, and there are records of them being dyed.

The sculpture in Pomata does not have crowns or feathers, so this specific iconographic feature is only present in the paintings, as a way to associate the image with the specific region of Pomata, as part of the territory of the specific bird whose feathers are used, as well as a way to connect it with the Indigenous practices of the area.

The textiles depicted as part of the dress of the Virgin and the Child are also connected to the textile tradition of the Andes. Each painting presents a different garment, all richly adorned with pearls, or perhaps beads. The rich green, white, red, and gold garments, with lavish embroidery, are present in every depiction of the Virgin of Pomata and connect to the specific practices of “dressing the Virgin” that the communities of each parish would perform on the special celebration days. The textiles, then, in each painting could connect to specific festivities, or to specific dates when the community of Pomata provided the garments, associating it with the value of textiles for the Indigenous communities of the Andes.

Unrecorded artist, Virgin of The Rosary of Pomata, c. 1730–60, oil on canvas with gold leaf applications (Pedro y Angélica de Osma Foundation)

Many paintings in many places

The multiplicity of painted versions of the Virgin of Pomata—all different, but with common traits—have been interpreted as a way for worshipers from outside of Pomata to carry a piece of the miraculous image with them and also to promote the cult of the Virgin. By commissioning a painting depicting the statue, as well as using the format of other paintings on the subject, the faithful would pay homage to the miraculous statue and also share their faith with their own communities in other parts of the Andean region. Places as distant as Colombia and Chile, at the far reaches of the Viceroyalty of Peru, have examples of these paintings, ones that connect a specific place, and sacred image, with local traditions and Indigenous practices.