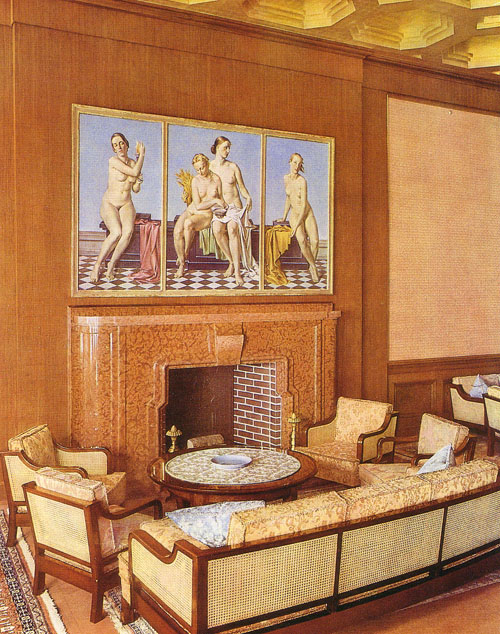

Adolf Ziegler, The Four Elements (Fire, Water and Earth, Air), before 1937 (Modern Art Collection, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich)

It comes as somewhat of a shock to many people that the first career choice of Adolf Hitler was not dictator and mass murderer, but something far more agreeable: visual artist. As a teenager, Hitler dreamed of entering the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. While he failed the entrance exam in 1907, he returned to the city and spent many years there painting small watercolors of streetscapes and landscapes, while living in shelters and boarding rooms. For the rest of his life Hitler fancied himself an artist and took pride in his aesthetic taste. To Hitler, art really mattered.

Adolf Ziegler, The Four Elements (Fire, Water and Earth, Air) hanging in the Kaminzimmer on the first floor of the Führerbau, Munich

Once in power, the Nazis systematically stole millions of works of art from both private individuals and public collections, in many of the countries which they conquered. Through this systematic expropriation, Hitler acquired a huge art collection and could have chosen from amongst the most celebrated masterpieces ever created to hang over a fireplace in his Munich apartment. So what did he choose? Adolf Ziegler’s The Four Elements: Fire, Water and Earth, Air. Who was Ziegler and what was it about this work that appealed to Hitler? Was there such a thing as “Nazi Art”? And how do we approach it?

Adolf Ziegler, celebrated artist in Nazi Germany

Although you almost certainly have never heard of him, Ziegler was about as celebrated a contemporary artist as there was in Nazi Germany. Ziegler joined the Nazi party in the 1920s and began advising Hitler on artistic matters many years before he was elected Chancellor of Germany. This set him up very well; in 1933 when Hitler and the Nazi Party took power, Ziegler was not only made a Professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, but in 1936 he was made President of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Künste), which controlled the production of every visual artist in the Third Reich (as the regime was called by those in the Nazi party).

Hitler had the opportunity to view a lot of Ziegler’s paintings at the annual exhibitions held at the House of German Art (Haus der Deutschen Kunst) in Munich. The large and imposing building was specially constructed for these exhibits, whose purpose was to show off the works of the “best” contemporary German painters and sculptors, that is those whom the upper ranks of the Nazis believed to be most worthy and reflective of the Reich’s values. Surprisingly, very few of the works were explicitly “political”; landscapes and genre scenes of peasants were especially favored. But in the Nazi totalitarian state all art was controlled, and all art was understood to have political valence—even if it seemed entirely divorced from politics.

While there was no singular “Nazi art” style, Ziegler’s Four Elements exhibits many traits common to works shown in the House of German Art. We might first notice its format, a triptych (a work clearly divided into three sections). Many medieval and Renaissance altarpieces (such as this one) took the form of triptychs, and they were used almost exclusively for religious images. This format therefore immediately announces the work’s spiritual or metaphysical significance. Likewise, the title of the work, The Four Elements (Fire, Water and Earth, Air) removes it from the mundane and real world, linking it to the Ancient Greek theory on the elements that made up the universe.

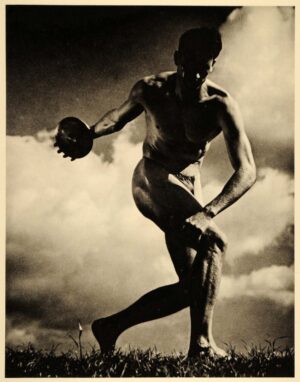

From Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938), clearly based on the ancient Greek sculpture of the Discobolos

The title also signals that the painting does not depict four real women, but rather is an allegory. In this case, Ziegler’s allegory is derived from the classical world. While some high-ranking cultural figures in the Nazi movement favored German medieval and folk art, Hitler himself saw classical art (the art of ancient Greece and Rome) as the highest achievement. His favored movie director, Leni Riefenstahl, created a film, “Olympia” (1938), about the 1936 Olympics which simultaneously served as an ode to classical beauty and classically proportioned bodies.

As noted, the format of The Four Elements alluded to celebrated altarpieces of the Renaissance. These references reflect the Nazi belief that they were the heirs of classical civilization, passed down through the Renaissance. (It certainly took a lot of pseudo-intellectual and pseudo-scientific mental gymnastics to argue how the Germans came to be the direct heirs of both the Greeks and the Italians).

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Street, Berlin, 1913, oil on canvas, 120.6 x 91.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

The Degenerate Art Exhibit, Munich, 1937

In addition to approved subjects, the style of Nazi-approved works was nearly always highly realistic. In 1937—the same year as Four Elements—Ziegler was instrumental in organizing the Degenerate Art Show, a gigantic exhibition held across from the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, with the aim of ridiculing modern and abstract art. The exhibition put forward the idea that use of unnaturalistic color and the distortions of the human body that appeared in the art of the period were the result of of mental or physical illness and/or racial degeneracy that were corrupting German culture.

Bearing the stamp of Nazi ideology

In contrast to modern art, in Four Elements, Ziegler gives no indication this is in fact a painting, but works hard to make the figures look almost photographic, seamless, and smooth. The precision gives the image an airless and cold feeling. There is something nearly eerie about the nudes, a result of their being highly idealized and perfected along the lines of classical art and yet highly individualized.

One man who saw the work in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst as a student remembered that they looked “almost pornographic” in their lifelessness and lack of animation. This may also have been the result of the fact that in contrast to almost the entire academic art tradition, the women in Ziegler’s paintings have body hair, resulting in his nickname, “The Reich Master of Pubic Hair.” [1] The presence of body hair contrasts sharply with the perfect symmetry and nearly marble-like smoothness of the women’s high breasts, unblemished skin and idealized form. The representation of such body types were meant to stir the desire of the male viewer, thus leading indirectly to the production of more children for the Reich. [2] Women’s highest role in Nazi society was to be the bearers of as many children as possible and thus to continue the “Aryan master race” (a disproven and racist belief that Northern Europeans were a racially “pure” and “superior” race). It is hardly an accident that all of the women are blonde and Nordic types, reflecting Nazi belief in racial superiority of the Germans. In this way even subjects seemingly far removed from political content nevertheless bear the stamp of Nazi ideology.

Adolf Ziegler, The Four Elements (Fire, Water and Earth, Air), before 1937 (Modern Art Collection, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich)

As the title makes clear, these are not “ordinary” women but rather personifications, or allegories, of the four elements. The woman on the far left carries a torch (“Fire”). Fire played a large role in the Nazi iconography as a symbol of both destruction and purity. (We might think both of Nazi torchlit rallies and of book burnings). Water is represented in a thoroughly unimaginative way, held in a small bowl. Earth is signaled by the sheaf of wheat, another beloved symbol in the Nazi repertoire for evoking their Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil) ideology, which held the farmer and the peasant to be the “truest” of Germans for being rooted to the land. To represent air, the artist shows a slight breeze waving the hair of the figure on the right.

While Ziegler clearly possessed great technical skills, the work traffics in obvious symbols and leaves no work for the viewer to do. It hardly engages, in any way, with the modern world or any form of modern conflict or concern. Ziegler is attempting to work in the vein of “high art,” while reflecting Nazi ideas of beauty, aesthetics, Greek philosophy, naturalism, and racial superiority. In that way it is similar to many works exhibited in the House of German Art and promoted by Nazi officials.

Christine Lehnen, “Calls for Nazi art in Munich to be taken down,” DW (October 7, 2022)

The exhibition of such works has raised serious issues, which continue to be debated. Should artists such as Ziegler, deeply tainted by his Nazi party membership, as well as his associations and artistic collaborations, be exhibited at all in the 21st century? Are we somehow celebrating or championing the artist by displaying his work? And what if we actually like it? While the works were seldom shown in the latter half of the 20th century, in the last decade or so many scholars and art historians have turned their attention to Ziegler and other official Nazi artists, believing that we must study them, not to honor them, but to understand their appeal and their aims. Whether we like it or not, these debates show that art can never be separated from the context in which it is created, especially when that context is one of the darkest chapters in human history.