Standing in front of a map of the United States, Colescott’s Miss Liberty inspires the question: who is afforded freedom?

Robert Colescott, Miss Liberty, 1980, acrylic on canvas, 213 x 183 cm (Art Bridges, Bentonville) © Estate of Robert Colescott. Speakers: Bill Conger, Chief Curator, Peoria Riverfront Museum, and Beth Harris

[music]

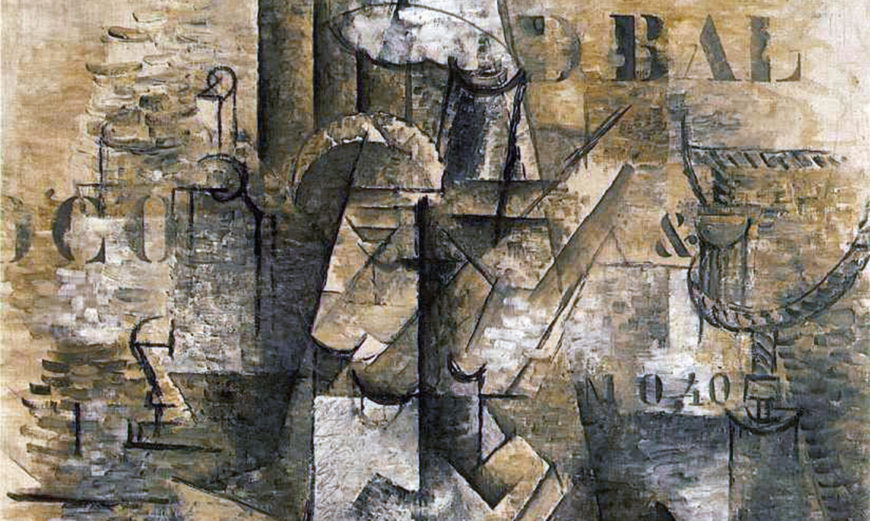

0:00:05.3 Beth Harris: We’re in the galleries at the Peoria Riverfront Museum, and we’re standing in front of a large, surprisingly large painting by Robert Colescott, Miss Liberty. And like so much of Colescott’s work, I find this challenging and that it takes time to decode and understand what’s happening.

0:00:25.8 Bill Conger: It is cryptic, and I think this confrontational quality of it as well, in terms of scale and relationship to the viewer.

0:00:34.5 Beth Harris: The colors don’t feel harmonious. They feel abrasive, as though they’re working against one another. In her dress, this red, yellow, and blue, these primary colors, but then these neon pinks and bright greens and purples and almost cotton candy pink, it demands our attention when we walk into the galleries.

0:00:55.3 Bill Conger: Although all this color is happening, it is her that you find.

0:00:58.3 Beth Harris: And she faces us. She takes up most of the canvas and seems to be almost looking out at an audience, as though she is seeking their attention, seeking our attention.

0:01:12.1 Bill Conger: And if we imagine our figure as, say, Miss America, the first African American Miss America wasn’t until 1984.

0:01:18.8 Beth Harris: The title of the painting is Miss Liberty. And so we have a slippage, I think, between an idea of a beauty pageant, but we also have the idea of the Statue of Liberty. Both of those associations are reinforced by the map of the United States that’s behind her.

0:01:37.7 Bill Conger: We are left with this cotton candy cloud with bits of garbage and refuse and beer cans, beer bottles. And where I think it goes is, why is this introduced into a concept that everywhere above this has no indication that something has gone wrong or that there’s some kind of contradiction being posed?

0:02:01.1 Beth Harris: There are signs to me in her figure and in the background that other things are also going wrong. We talked about the colors and their discordance, but there’s also something about the way that she’s over made up, that we can see the red on her cheeks, like she’s applied too much blush. There’s the red of her lipstick. These feel discordant to me in a way that I can’t really even identify why, because, of course, the woman who becomes Miss America wears lots of makeup, has her hair done the way that this woman does. Colescott is making me feel uncomfortable.

0:02:39.4 Bill Conger: It’s not the viewer looking at the painting. In a sense, it’s the painting looking at the viewer and revealing all sorts of things about the viewer’s perspective and preconceptions about imagery and everything from race to gender to nationalistic ideas, et cetera, et cetera.

0:02:55.7 Beth Harris: We have that first level of seeing a Black figure in a place where we expect to see a white figure. So that’s the first level of discordance. And I’m aware of my own expectations of what I should be seeing here, not only with her but how I should be seeing a map of the United States.

0:03:14.7 Bill Conger: I don’t think it’s correct. I think there are a lot of things removed and/or left out. He has also left it somewhat unfinished. The eastern coastline has only been filled in a certain amount with blue. There is an unfinishedness and this idea that this is very much a project in the making.

0:03:33.1 Beth Harris: That peachy color where the blue doesn’t extend has been bothering me. I just keep asking, why doesn’t the blue, which clearly symbolizes the water here and in most maps that we look at, why doesn’t it extend up the eastern seaboard? Is there a reference to the thirteen colonies, to our connection to Europe? Perhaps, because there’s no sea in between, it feels very open to interpretation, like so much of what we see here.

0:04:01.7 Bill Conger: Within this single frame, he’s able to unlock many things that would make the viewer feel uneasy and potentially self-curious.

0:04:11.8 Beth Harris: I think about it in the history of art, I think there are allegorical figures of liberty, and they usually hold attributes, but she’s not holding attributes. She could be, like we said, Miss America, but she doesn’t have that Miss America crown, and what she’s wearing doesn’t really fit that either. Nothing fits here.

0:04:32.5 Bill Conger: For some reason, I am seeing the heightened color choices for the states as being something about a disconnect. And I agree the pink on the right just breaks the map apart and challenges the representation of the map. And ironically, she is draped with stars, yet the red and white stripes don’t exist, a very curious choice given that she’s obviously adorned with the primary colors. And then we haven’t mentioned this purple cape that I think alludes to maybe some royalty or some kind of elevated status of some kind, but there is this idea that things are right and not right, all at the same time.

0:05:14.1 Beth Harris: For me, some of the most beautiful passages in the painting are that purple and red of the cape that she’s wearing. As it falls beautifully, you get a sense of its texture, of the weight of the fabric, the ermine around her collar. It does suggest royalty, then it looks back to Grand Manner portraiture of the 18th century, where again, we would expect to see an elite white person.

0:05:41.8 Bill Conger: And we haven’t yet discussed a tiny little indication of the identity of the maker, of Robert himself, with a star around the Oakland, California locale, which is where he was born.

0:05:54.5 Beth Harris: As soon as we think about the title, Miss Liberty, and we see this Black figure in front of us, the irony there of the promise of liberty and who was afforded liberty, who was afforded freedom, and the continued issues around that promise of the United States is clearly here.

[music]