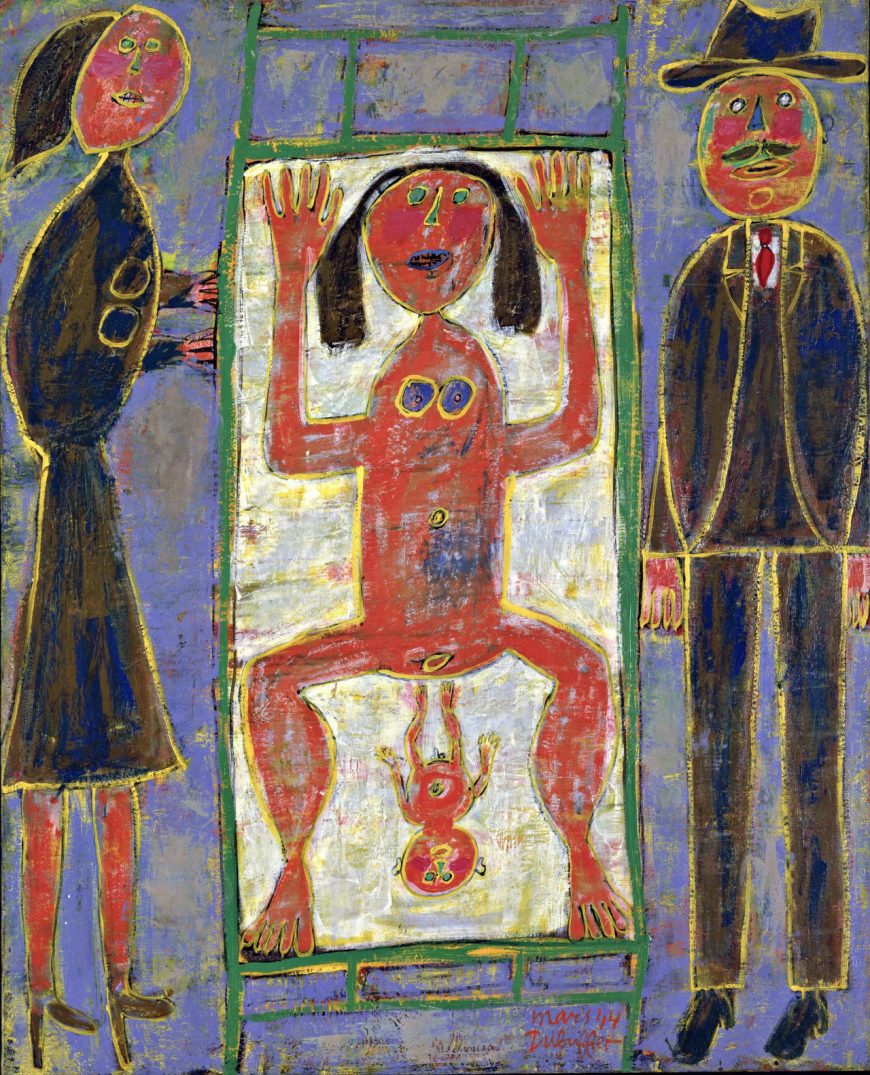

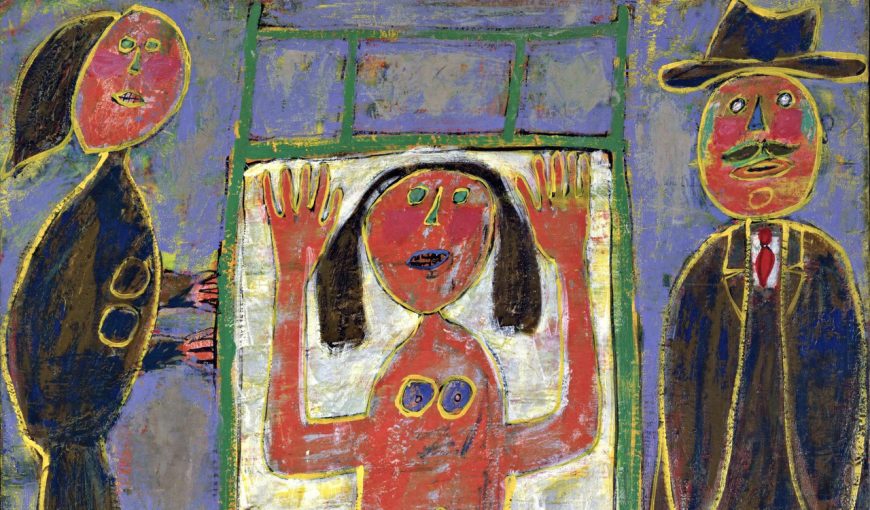

Jean Dubuffet’s Childbirth is a particularly striking work of art, but not because it’s aesthetically pleasing. In fact, Dubuffet intended quite the opposite. He wanted his art to disturb his viewers. Perhaps, the most jarring aspect of this painting is the central image of a mother giving birth. The figure has been flattened and tilted forward toward the picture plane (the surface of the canvas). Her hands are raised, as if gesturing “STOP!” or as if signaling shock or fear. Also arresting are the figure’s rounded eyes, which open wide to gaze confrontationally toward the viewer, or alternately, off into space, suggesting an image of trauma. Dubuffet used these compositional strategies, combined with rough looking brushwork, pronounced outlines, and both murky and vivid colors to achieve this unnerving impact. He wanted his painting to be so agitating that it would change the way people look at art, the way people feel about art, and even the ways we define what art is. Dubuffet believed art was a liberating encounter that had been suppressed by museums, commercial art galleries, and other cultural institutions.

Figure (Bioma), early to mid-20th century, Wapo People, Papua New Guinea, wood and paint, 57.5 x 18.7 x 3.2cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Art Brut

Dissatisfied with artistic practices that had persisted since the Italian Renaissance, many painters in the early twentieth century sought to invigorate their art with pictorial forms that challenged the European tradition. When Dubuffet began painting professionally during WWII, he turned for inspiration to radically alternative imagery, including children’s drawings, the art of the mentally ill, and other marginalized artists. He coined the term Art Brut (raw art) to describe the raw, untrained qualities he wanted to emulate in his painting. Like other artists of this period, Dubuffet also drew on various types of non-Western art for inspiration.

The desire to infuse art with primal creativity led artists like Dubuffet to erroneously conflate the art of children, mental patients, and non-Western cultures. They lumped together the pictorial forms these sources inspired and called them “primitivist” Primitivism became a loosely defined style, characterized by the visual contrast to established artistic conventions; and works such as Dubuffet’s were either celebrated by fans or derided by hostile critics for their apparent crudeness. Although people today acknowledge primitivism’s Eurocentricism (primitivism critiques Western culture while nevertheless privileging it), it is important to note that for these artists, “primitive” meant art that is essentially free from, and subversive to, Western cultural traditions. For Dubuffet, this was what art should really be about—a primal creative act.

Primal creation

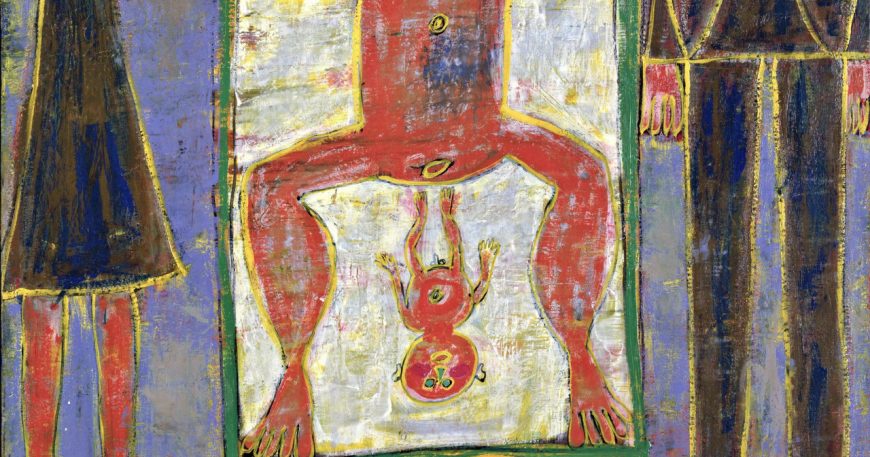

The painting Childbirth is filled with references to non-Western art, particularly the art of the Pacific Islands. French Surrealist artists with whom Dubuffet associated, believed such art was an expression of primal creativity. For example, the central figure with raised arms is a motif seen in art from Papua New Guinea (above) that can sometimes refer to fertility and kinship. Dubuffet’s used the image both for its subject, which may have signaled the primal creative act of childbirth for the artist, but also for its formal qualities, particularly the linear design and flattened forms. By emphasizing the flat canvas surface, Dubuffet reminds the viewer that the painting is a representation of reality, in contrast to Renaissance painters who relied on the illusionism of linear perspective (an artistic device used to create the illusion of depth in a painting) to create idealized scenes as though seen through a window.

Dubuffet plays with the notion of framing in his composition. The flattened figures of the mother and child have been tipped up so that the white rectangle of the hospital gurney presses forward rather than receding back into space, with its legs shown parallel to the floor. This is one of the ways Dubuffet subverts Renaissance perspective by calling attention to the canvas surface. Bluish colored rectangles surround the white rectangle of the gurney, creating planes occupied by the figures on the left and right that frame the child’s birth.

In Dubuffet’s painting, these outside figures could represent a mother and father (perhaps the woman’s parents) or perhaps the father of the child and another female participant, such as a sister or midwife. These figures are also crudely rendered, and may symbolize parenthood in general. A key difference is that these visitors wear Western garb whereas both mother and child are nude, a more natural state that that represents the act of childbirth.