Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas), 1939, oil on canvas, 67-11/16 x 67-11/16″ (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City)

Sixty, more than a third of the easel paintings known by Frida Kahlo are self-portraits. This huge number demonstrates the importance of this genre to her artistic oeuvre. The Two Fridas, like Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair, captures the artist’s turmoil after her 1939 divorce from the artist Diego Rivera. At the same time, issues of identity surface in both works. The Two Fridas speaks to cultural ambivalence and refers to her ancestral heritage. Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair suggests Kahlo’s interest in gender and sexuality as fluid concepts.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940, oil on canvas, 40 x 27.9 cm (Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City)

Kahlo was famously known for her tumultuous marriage with Rivera, whom she wed in 1929 and remarried in 1941. The daughter of a German immigrant (of Hungarian descent) and a Mexican mother, Kahlo suffered from numerous medical setbacks including polio, which she contracted at the age of six, partial immobility—the result of a bus accident in 1925, and her several miscarriages. Kahlo began to paint largely in response to her accident and her limited mobility, taking on her own identity and her struggles as sources for her art. Despite the personal nature of her content, Kahlo’s painting is always informed by her sophisticated understanding of art history, of Mexican culture, its politics, and its patriarchy.

The Two Fridas

Exhibited in 1940 at the International Surrealist Exhibition, The Two Fridas depicts a large-scale, double portrait of Kahlo, rare for the artist, since most of her canvases were small, reminiscent of colonial retablos, small devotional paintings. To the right Kahlo appears dressed in traditional Tehuana attire, different from the nineteenth century wedding dress she wears at left and similar to the one worn by her mother in My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree) (1936).

Frida Kahlo, My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree), 1936, oil and tempera on zinc, 30.7 x 34.5 cm (Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City)

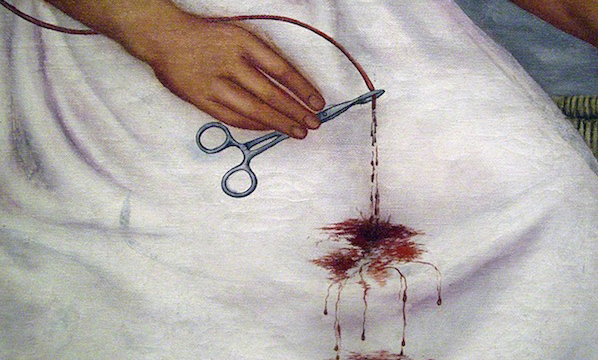

Whereas the white dress references the Euro-Mexican culture she was brought up in, in which women are “feminine” and fragile, the Tehuana dress evokes the opposite, a powerful figure within an indigenous culture described by some at the time as a matriarchy. This cultural contrast speaks to the larger issue of how adopting the distinctive costume of the indigenous people of Tehuantepec, known as the Tehuana, was considered not only “a gesture of nationalist cultural solidarity,” but also a reference to the gender stereotype of “la india bonita.” [1] Against the backdrop of post-revolutionary Mexico, when debates about indigenismo (the ideology that upheld the Indian as an important marker of national identity) and mestizaje (the racial mixing that occurred as a result of the colonization of the Spanish-speaking Americas) were at stake, Kahlo’s work can be understood on both a national and personal level. While the Tehuana costume allowed for Kahlo to hide her misshapen body and right leg, a consequence of polio and the accident, it was also the attire most favored by Rivera, the man whose portrait the Tehuana Kahlo holds. Without Rivera, the Europeanized Kahlo not only bleeds to death, but her heart remains broken, both literally and metaphorically.

Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair

Frida Kahlo, detail with hemostat, The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas), 1939, oil on canvas, 67-11/16 x 67-11/16″ (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City) (photo: Dave Cooksey, CC: BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In opposition, the painting Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair boldly denounces the femininity of Two Fridas. In removing her iconic Tehuana dress, in favor of an oversized men’s suit, and in cutting off her braids in favor of a crew cut, Kahlo takes on the appearance of none other than Rivera himself. At the top of the canvas, Kahlo incorporates lyrics from a popular song, which read, “Look, if I loved you it was because of your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you anymore.” In weaving personal and popular references, Kahlo creates multilayered self-portraits that while rooted in reality, as she so adamantly argued, nevertheless provoke the surrealist imagination. This can be seen in the visual disjunctions she employs such as the floating braids in Self Portrait with Cropped Hair and the severed artery in Two Fridas. As Kahlo asserted to Surrealist writer André Breton, she was simply painting her own reality.