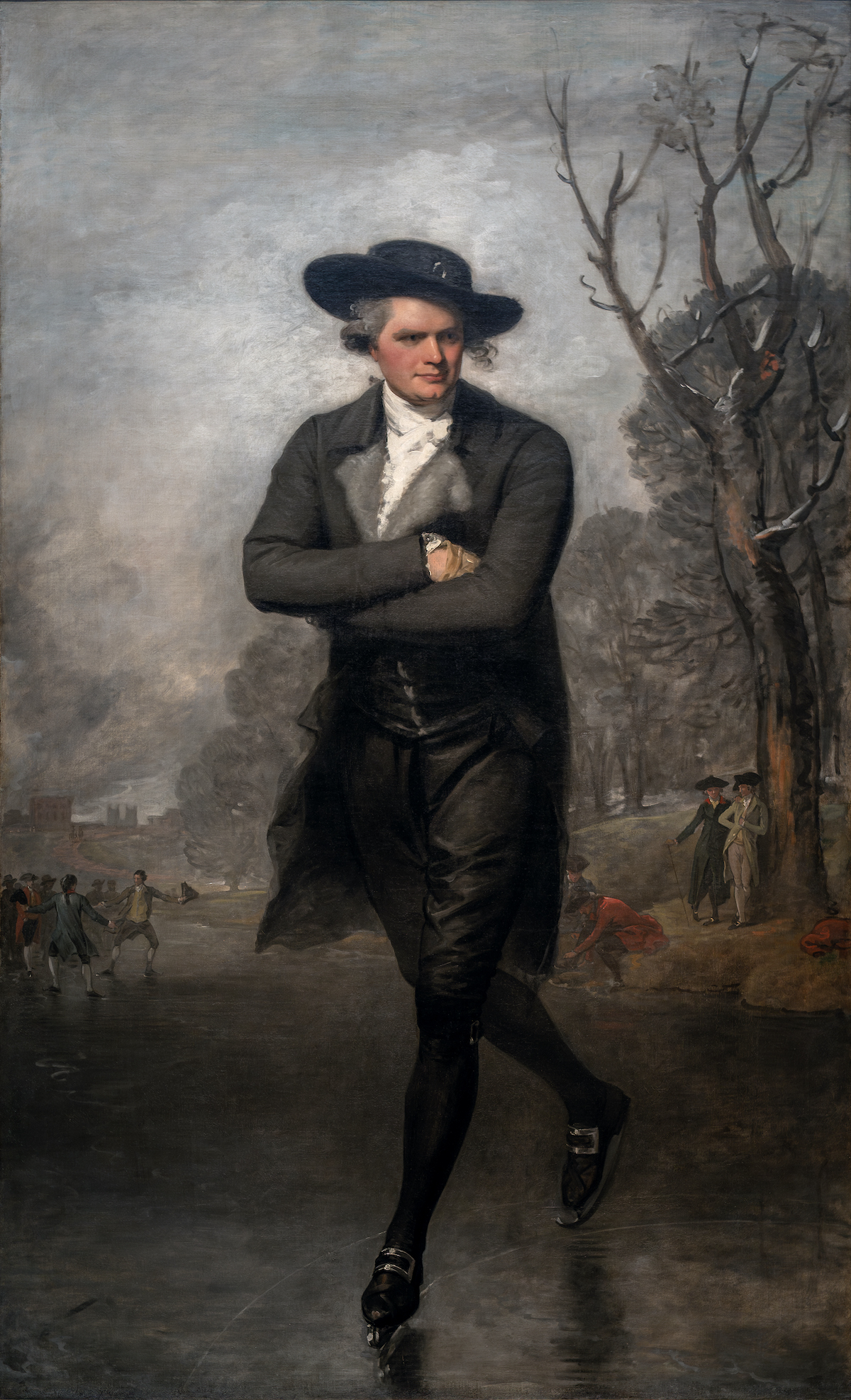

Depicting his subject in motion was a departure from the norm, making this painting the talk of the town.

Gilbert Stuart, The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), 1782, oil on canvas, 235.5 x 147.4 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Speakers: Dr. Bryan Zygmont and Dr. Beth Harris

[music]

0:00:05.8 Dr. Beth Harris: We’re in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., looking at what I think of as an iconic American painting.

0:00:13.7 Dr. Bryan Zygmont: This portrait of William Grant, commonly called the Skater, was a turning point in the career of Gilbert Stuart. Prior to this, Stuart’s career was one that was a bit uneven. Stuart was born in 1755 in what would later be Rhode Island. And when a young man, 20 years old, he went to London to seek his artistic fortune. After a couple of years, he was destitute, he was alone, and he wrote a letter to Benjamin West asking for help. And Benjamin West, being the incredibly good-natured man he was, brought Stuart into his home, provided him with some art teaching, and within a couple of years, it seems clear to me that Stuart had far surpassed his teacher in the art of portraiture.

0:01:02.8 Dr. Beth Harris: And this is such an unusual portrait for the simple fact that the figure is shown skating.

0:01:09.1 Dr. Bryan Zygmont: One of Stuart’s great gifts was not only depicting what a sitter looked like, which, of course, is one of the goals of portraiture, but he was able to imbue his portraits with a kind of personality. And certainly this image of a young Scottish lawyer ice skating is unique in the history of British art.

0:01:30.5 Dr. Beth Harris: So we might notice the arms folded across the chest, but this was a very common way for figures to hold their upper body while they were skating, so it wasn’t at all unusual. But it’s the way he turns his shoulders one way, his head another. It’s just a figure that is so filled with movement, but movement that seems so natural and so graceful.

0:01:55.5 Dr. Bryan Zygmont: You took my word. It is an image of grace and almost effortlessness as he glides across this frozen lake on his way towards the viewer.

0:02:06.0 Dr. Beth Harris: The light is so carefully considered, how one side of his face is in shadow, the other side is fully illuminated. We have this curve of his hat, the curve of his arms, the curve of that tree behind him, the landscape that seems to also move from the right to the left, the way that the figure does. Everything about this fits together so perfectly.

0:02:30.5 Dr. Bryan Zygmont: There’s very little color in this composition, and yet it has a kind of vibrancy and life to it.

0:02:36.3 Dr. Beth Harris: To me, those blacks and grays suggest a kind of sophistication, someone who is very fashionable, clearly a member of the upper classes.

0:02:45.7 Dr. Bryan Zygmont: Stuart’s career after this painting was entirely different. In 1782, he was still living and working with Benjamin West. The year following this, he had one of the most fashionable portrait studios in all of London. In the years that followed, he departed for Dublin, where he painted the Protestant aristocracy for a number of years, but his goal was always to return to the United States. And when he did, he had one major objective. He wanted to paint the first President of the United States. And paint George Washington, he did. Not dozens, but scores of times. And perhaps the most famous image in the history of American art is his portrait of George Washington that now sits on the American dollar bill.

0:03:32.6 Dr. Beth Harris: What we see in this portrait is an artist who has clearly absorbed all of the lessons of the Renaissance, of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture.

0:03:41.8 Dr. Bryan Zygmont: When we look at this image, it’s easy to imagine the Apollo Belvedere, an image that Stuart would have known through reproductions through his time studying with Benjamin West.

0:03:51.5 Dr. Beth Harris: The silvery colors suggest snow and ice and this cold winter day. And in fact, some art historians have seen this painting as an allegory of winter as much as it is a portrait. And our eye goes to the two well-dressed figures in the middle ground on the right and two other figures, one of whom is tying his skate, the other group of figures who seem so joyous in their skating. But our eye, thanks to the composition, is always drawn back to William Grant’s face and what feels to me like his youth and his self-composure and self-assuredness.

0:04:31.4 Dr. Bryan Zygmont: It’s clear that this is a cold day and yet the face of William Grant seems to have a kind of warmth and vibrancy about it. When this painting was shown at the 1782 Royal Academy show, Gilbert Stuart was, for all intents, an unknown artist. But as the decades moved on, Stuart became the most accomplished portrait painter in the history of the United States.

[music]

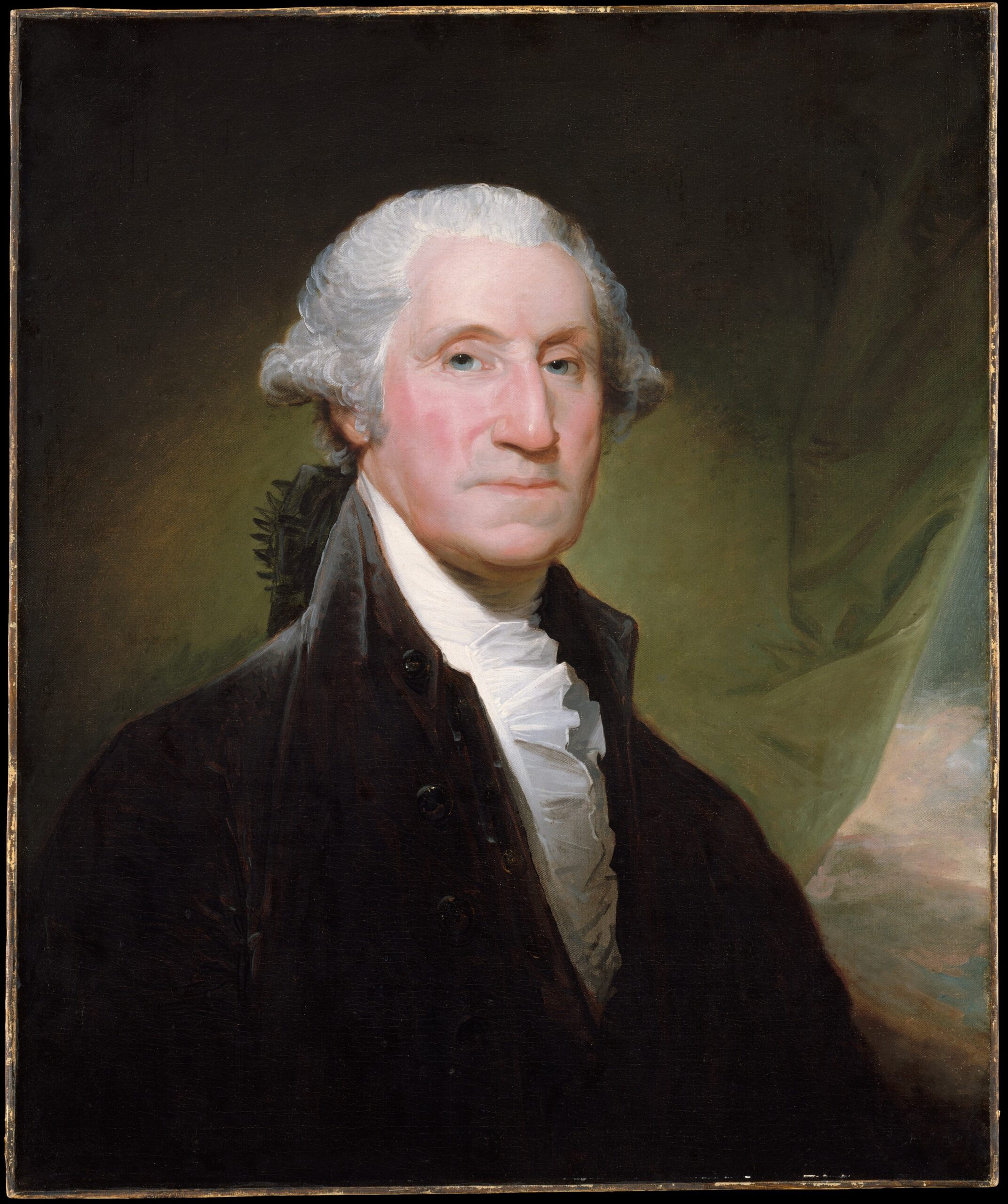

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, begun 1795, oil on canvas, 76.8 x 64.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The fame of Gilbert Stuart today rests on the dozens of portraits he painted of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Indeed, Stuart painted so many likenesses of the first president between arriving in Philadelphia in 1795 and his death more than thirty years later that he often joked that the act of painting Washington’s face was akin to painting a $100—his normal fee. Yet Stuart’s story begins long before Philadelphia and long before he met President Washington.

The colonies, Scotland, and back again

Stuart’s story begins in the American colonies. He was born just outside Newport, Rhode Island in 1755. At a young age he demonstrated an artistic proficiency—a talent that was aided when Cosmo Alexander arrived in Newport. Alexander was a Scottish-born and Italian-trained itinerant artist who was then working his way northward along the eastern seaboard. He possessed knowledge of European art largely unmatched in the American colonies. Alexander was clearly enchanted by the fourteen-year-old and provided Stuart with painting and drawing lessons. Then, in 1771, Alexander offered to continue the youngster’s education in Scotland. Unfortunately for Stuart—and, for that matter, Alexander himself—the older artist died not long after the pair crossed the Atlantic. Although Stuart attempted to pursue a career as a portraitist in Scotland, he lacked the credentials, connections, skill, and training to make a successful go of it.

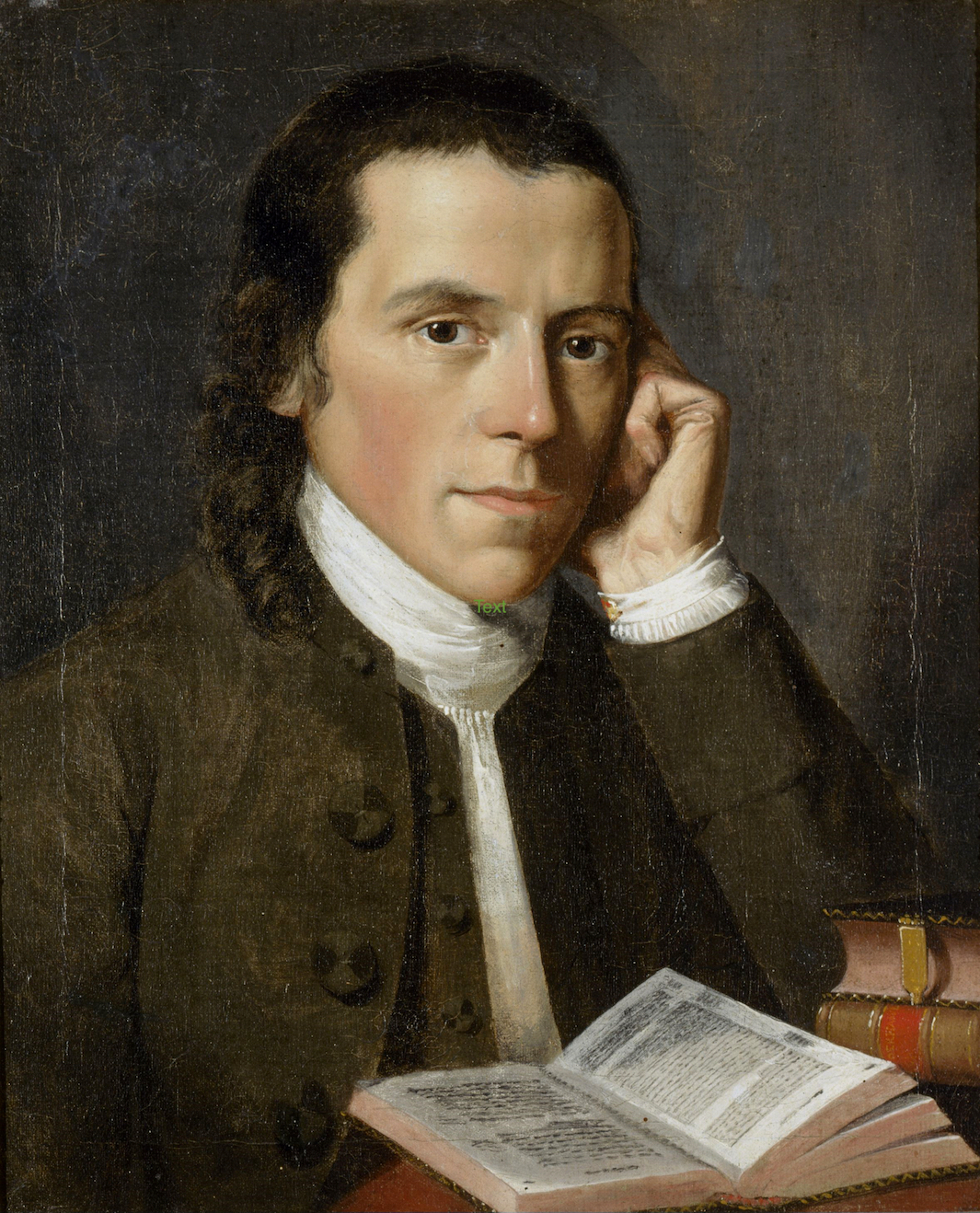

Gilbert Stuart, Benjamin Waterhouse, 1775, oil on canvas (Redwood Library and Athenaeum, Newport, Rhode Island)

And so, no doubt with more than a small amount of shame, Stuart returned to Newport in 1773. Embarrassed though he may have been at his failed attempt to be a portraitist in Europe, Stuart was productive once he returned to the American colonies. Some of the portraits he completed between 1773 and 1775 are accomplished likenesses for a portraitist with little formal artistic education. For example, Stuart painted a close friend, Benjamin Waterhouse. When Stuart painted this portrait in January 1775, Waterhouse was already planning to pursue medical training in London. Stuart hoped to join him there, but by the time Stuart departed for London in November 1775, his friend had already relocated to Scotland to study at the University of Edinburgh Medical School.

London and an appeal to Benjamin West

Thus, Stuart arrived in London with no friends or social connections, and he lacked a formal letter of introduction to the North American born Benjamin West—then the toast of the London art community. Instead, Stuart found employment at Saint Catherine’s Church as on organist, receiving a modest salary of 150 pounds per year. About a year later—mid-December 1776—Stuart seemed to have hit rock bottom. He arrived at Benjamin West’s studio at 14 Newman Street with a letter written to his countryman begging for assistance. Filled with Stuart’s creative grammar, punctuation, and spelling, it is worth quoting at length:

Pitty me Good Sir I’ve just arriv’d at the age of 21 an age when most young men have done something worthy of notice & find myself Ignorant with Business of Friends, without the necessarys of life so far that for some time I have been reduced to one miserable meal a day & frequently not even that, destitute of the means of acquiring knowledge, my hopes from home Blasted & incapable of returning tither, pitching headlong into misery I have this only hope I pray that it may not be too great, to life & learn without being a Burthen Should Mr West in has abundant kindness think of ought for me.

Not surprisingly, West took pity on Stuart. Shortly thereafter—January 1777 is likely—West hired Stuart as a resident assistant. West provided Stuart with room and board and paid him one-half guinea a week to paint draperies within his teacher’s portraits. West’s charity and recognition of Stuart’s talent and potential was a pivotal moment in the younger artist’s career.

Although West had made his fame as painter of historical compositions, he was content to allow Stuart to focus on portraiture, the genre of art Stuart knew would dominate his artistic output whenever he returned to his homeland. By all accounts, Stuart was a quick study and an attentive pupil. In five years—that is from 1777 until 1782—he absorbed, and some might say mastered, the painterly mode of portraiture that was fashionable in London during the second half of the 18th century.

Gilbert Stuart, The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), 1782, oil on canvas, 235.5 x 147.4 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Skater

No painting announces Gilbert Stuart’s coming of age as an portraitist quite like that of his likeness of William Grant, an image now affectionately called The Skater. Stuart displayed this painting at the 1782 exhibition of the Royal Academy of Art. During the 1780s, one might find hundreds of bust-length portraits on the walls of this annual show. However, Stuart’s portrait of Grant was what was then called an exhibition piece—an ambitiously sized full-length portrait that often explored not only what a sitter looked like, but also who a sitter was. Artists aspired for grand paintings such as The Skater to be hung “on the line,” a place reserved for large compositions that the artist intended to be seen from a certain distance. Measuring more than eight feet tall and almost five feet across, Stuart believed The Skater would advertise his artistic maturity and his transition from Benjamin West’s student to Benjamin West’s protégé.

Rather than identify the sitter by name, the exhibition catalogue listed the title only as Portrait of a gentleman skating. And, indeed, Stuart was deliberate in the ways in which he accentuated Grant’s social status through the use of attire. Grant wears white, grey, and black, then the preferred clothing for the social elite. His suit is made from fine black silk velvet, and his knee-length frock coat is accentuated with fashionable grey fur lapels. His black beaver hat—round and broad—was likewise of the most recent fashion. Grant’s winter-inspired florid cheeks represent the only dash of color in the painting’s foreground.

Bust of William Grant (detail), Gilbert Stuart, The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), 1782, oil on canvas, 235.5 x 147.4 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Background with Westminster Abbey towers (detail), Gilbert Stuart, The Skater (Portrait of William Grant), 1782, oil on canvas, 235.5 x 147.4 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Although painted almost 90 years prior to James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s portrait of his mother—the so-called Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, 1871—Stuart’s The Skater is likewise a harmonious composition that largely involves value (light and dark) rather than color. Stuart renders the sky, the frozen Serpentine River in Hyde Park, and the recognizable twin towers of Westminster Abbey along the horizon line on left of the composition all in shades of grey.

Joshua Reynolds, Captain the Honourable Augustus Keppel, 1752–53, oil on canvas, 239 x 147.5 cm (National Maritime Museum, London)

Skating

Grant’s skating pose may seem unusual to a 21st-century audience, but it was one instantly recognizable to the visitors to the 1782 Royal Academy exhibition. His weight-bearing left leg and slightly bent right leg is a near mirror image of the lower body of the Apollo Belvedere, perhaps the most famous of classical Greek sculptures in the 18th century, and a cast of which stood in the corner of West’s studio. Grant’s upper body—his arms folded across his chest—was a pose typical to ice skaters of the 18th century, for its nonchalance accentuated the effortlessness of skater’s movement. In fact, the motion Stuart shows is one reason why The Skater was so novel. Full-length “grand manner” portraits of the 18th century generally showed the subject standing still.

Rarely, portraitists depicted their subject striding forwards as if to walk. For example, in his Captain the Honourable Augustus Keppel, Joshua Reynolds—recently returned from Italy—also referenced the pose of the Apollo Belvedere to suggest the young naval commander moving ashore. However, showing the sitter (think about that word: the sitter!) in motion—let alone rapidly moving as one does when ice-skating—was unique. The normally light-on-the-praise Horace Walpole wrote “very good” in the margin next to Stuart’s entry in the exhibition catalogue. Indeed, Gilbert Stuart’s The Skater was one of the most discussed portraits of the 1782 Royal Academy exhibition, and this work of art launched him to an extraordinarily successful career as a London portraitist. Twelve years—and a stopover in Dublin—later, Stuart was again on North American shores and set to paint his most famous images, those of President Washington.