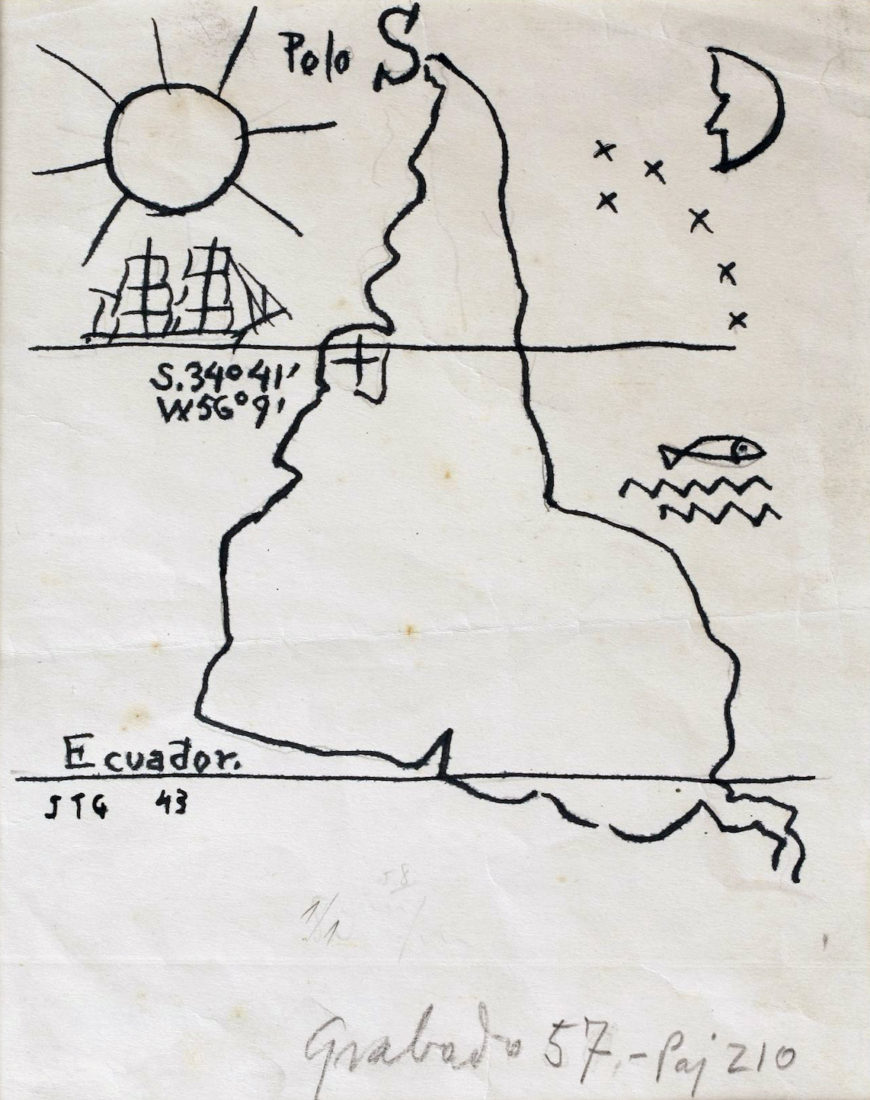

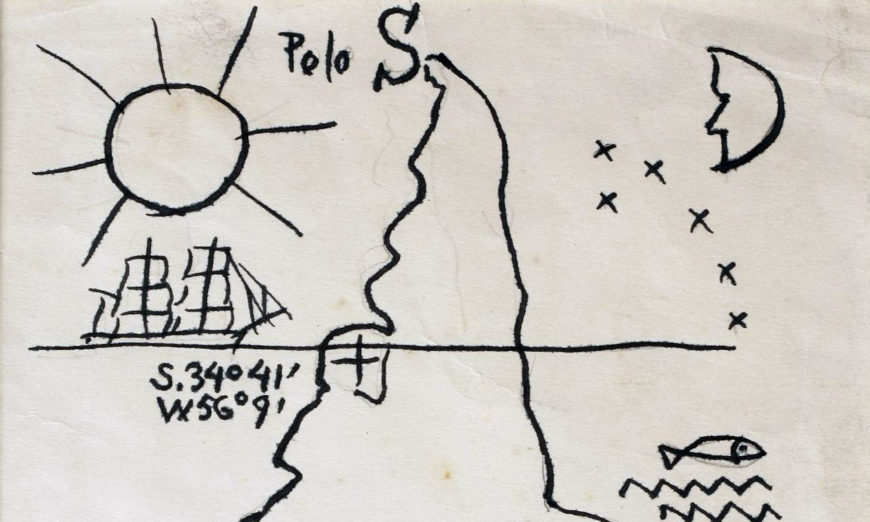

Joaquín Torres-García, América Invertida (Inverted America), 1943, ink on paper, 22 x 16 cm (Fundación Torres García, Montevideo)

“Our North is the South.”

So Joaquín Torres-García proudly announced in 1935 in The School of the South Manifesto, in which he articulated his ideas about the direction of Uruguayan, and indeed all Latin American art. Torres-García upended traditional hierarchical structures by defining the art of South America on its own terms, rather than in relation to that of the North (i.e. the United States and Europe) as it had been in the past. In proclaiming itself independent from artistic centers of power like New York and Paris, Torres-García looked to the pre-Columbian past (before the arrival of Christopher Columbus to the Americas in 1492) as a source of artistic inspiration.

In 1934, Torres-García returned to Uruguay from the United States and Europe, where he had lived for roughly 40 years. Upon his return, he established the School of the South, a workshop in which he encouraged students to seek inspiration locally rather than globally, while at the same time establishing an autonomous artistic tradition. As seen in América Invertida (Inverted America), the aim of Torres-García was to challenge the traditional frame of mind, and reposition the South as the new North.

Joaquín Torres-García, América Invertida (Inverted America), 1943, ink on paper, 22 x 16 cm (Fundación Torres García, Montevideo)

Inverted map

With the southern cone turned upside down, one sees the map of South America in an entirely new way. The map communicates important details like the cardinal direction of the South, the latitude line of Montevideo, and the equatorial line. Rather than show the equator at the center of the hemisphere, as is usually the case, Torres-García instead places Uruguay in this privileged position. Other symbols like the sun, boat and fish seem relatively straightforward, however for Torres-García they also communicated greater meaning.

Joaquin Torres-García, Cosmic Monument, 1938, Montivideo, Uruguay

Appearing often in his work, the sun is a powerful pre-Columbian symbol. Due to its life giving force, Torres-García prominently features it, not only in this map, but also in his Cosmic Monument, where it appears at the center. The boat is usually associated with travel, while the fish represents fecundity.

Gate of the Sun, Tiwanaku, 500 and 900 C.E., La Paz, Bolivia (photo: thoew, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Torres-García argued that these symbols were indigenous to Latin America and featured in monuments as old as the ones found in Tiwanaku (one of the most prominent civilizations in South America prior to the Inca empire). As a result of their ancient origins and timeless quality, Torres-García held that these were universal symbols. In the Gate of the Sun at Tiwanaku the Sun God faces out from the top of the gate with rays around his face. Pre-Columbian symbols here joined the great art of ancient civilizations, along with the hieroglyphics of the ancient Egyptians and the reliefs of the ancient Greeks. Torres-García drew on quintessentially Latin American symbols to articulate a version of modern art that was autonomous from what he had seen in Barcelona, Paris and New York, thus reaffirming his cultural identity, while simultaneously articulating a new direction.

Constructive Universalism

Constructive Universalism, as he referred to this new style, sought to imbue geometric art with a new spiritual dimension, here achieved through the appropriation of ancient symbols.

Diego Rivera, Triumph of the Revolution, 1926, Autonomous University of Chapingo, Mexico (photo: Joaquín Martínez, CC BY 2.0)

Abstraction and figuration were at odds with each other at this time, when other Latin American artists like Mexican Diego Rivera (above), Ecuadorian Camilo Egas, and Brazilian Candido Portinari championed figural depictions of local subjects rooted in social activism. Interestingly, Torres-García upheld both the principles of abstraction and a regional sense of identity, while eschewing any socio-political message.

While pre-Columbian art was at the center of Constructive Universalism, Torres-García also looked to astral, zodiacal, and other ancient signs, explaining the presence of the star and the yin and yang in his Cosmic Monument (above). The conflation of these influences demonstrates the international nature of his work, despite its emphasis on Latin American culture.