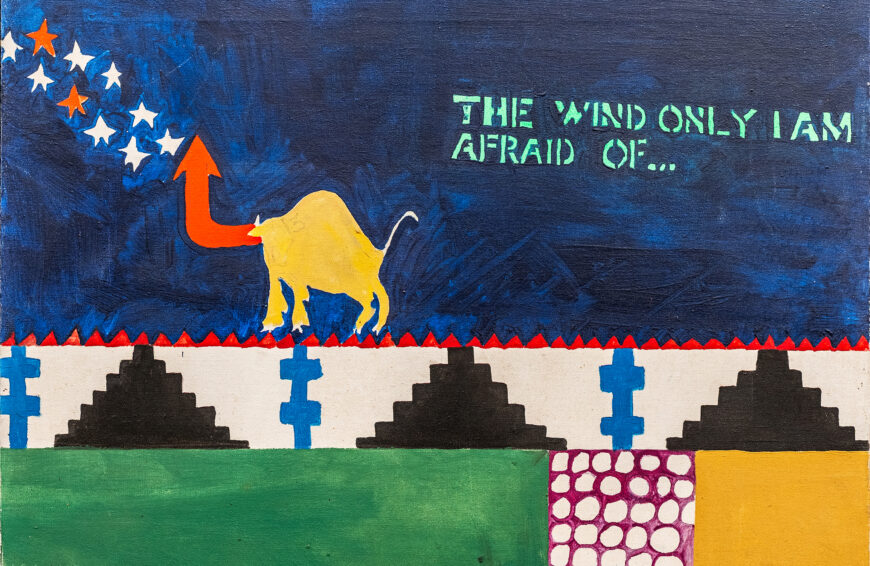

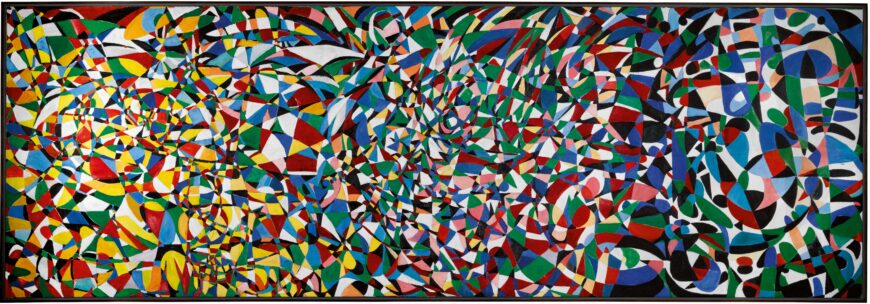

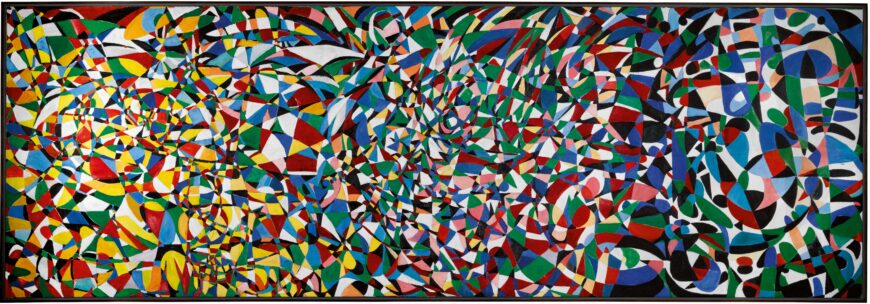

Fahrelnissa Zeid, Towards a Sky, 1953, oil on canvas, 593 x 201 cm (private collection; photo: Sotheby’s, 2017) © Fahrelnissa Zeid Estate

When Fahrelnissa Zeid exhibited her painting Towards a Sky in 1953, it took six handlers to install at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. The following year, 1954, one third of the canvas had to be rolled up in order to fit the work into the space of London’s Institute for Contemporary Art (Zeid was the first woman to have a solo exhibition there). She reworked and repainted sections of it as she usually did to her works, then re-exhibited it in London in 1957, in the garden of Lord’s Gallery. The painting was mounted on a special frame, punctured around the edges and strung in place like a sail, soaring three floors high.

Originally 7 meters tall, the painting now measures 5.93 by 2.01 meters (233-1/8 by 79 inches). Zeid cut off a section, but both parts reappeared publicly sixty years later and were sold separately by different auction houses. This colossal work is not her largest extant painting, however. That would be her 1949 painting Voyage of the Man Moon, measuring 6 x 1.6 meters and shown for the first time in New York in 1950. Since she began exhibiting in 1941 back in her native Istanbul, Zeid favored large formats averaging two meters, larger than a human body. And from 1949 to the mid-1960s, she produced monumental works averaging 5 meters in length.

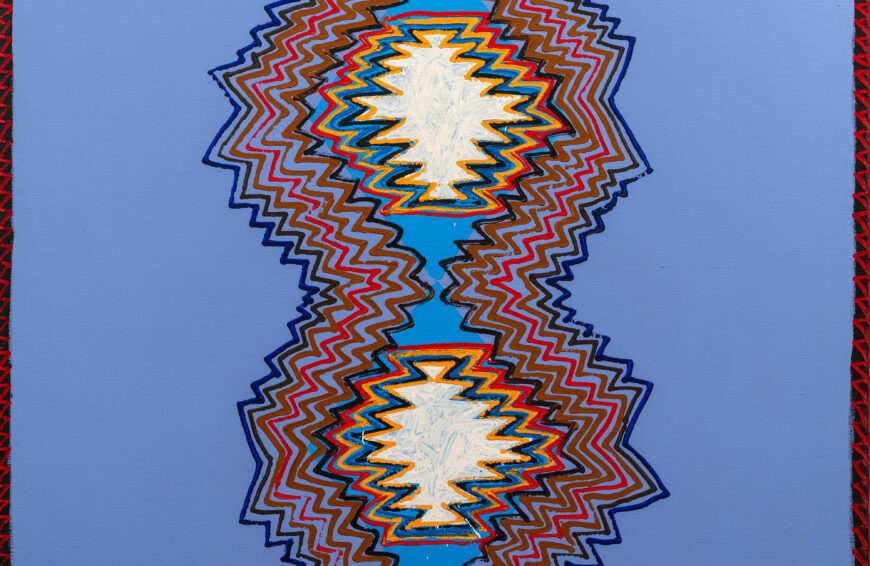

Fahrelnissa Zeid, A Study for Towards a Sky, 1953, oil on canvas, 52 x 105 cm (private collection; photo: Bonham’s, 2017) © Fahrelnissa Zeid Estate

Looking at this painting on a screen is misleading, because it does not dominate the viewer’s field of vision as it does in real life. But the impression of its vortex of colors and shapes is as strong as when it was seen up close in that garden in London, when the critic George Butcher wrote about how before sunset, its entire glowing surface dominated the space, transforming life around it; how it seemed to grow in some organic way out of the ground, and towards the sky. Another critic, Terence Mullaly, noted that the painting’s size was irrelevant, because what mattered more was Zeid’s persuasive vision and her extraordinary ability to speak through color.

The melodic and the symphonic

This work illustrates a most accomplished period in Zeid’s fifty-year-long career as the only non-European, female, mid-20th-century modern artist to have regularly produced monumental paintings.

The painting evokes the sublime in its boundlessness, a quality we may associate with Abstract Expressionism, and the movement’s characteristic emotionally charged non-figurative imagery. But Fahrelnissa Zeid arrived at such awe-inspiring results via a distinct trajectory.

She found inspiration in Vassily Kandinsky’s spiritualist theorization of abstract art, in which she recognized her own approach and an articulation of her exalted state of mind while working. This interest may be traced to the 1951 launch of a new French translation of his 1911 book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, at the opening of her second Paris exhibition. Zeid’s Towards a Sky, like other works she produced during that period, illustrates some of Kandinsky’s prescriptions: rhythm, seemingly antagonistic compositional subdivisions, and a concealed inner harmony.

Advocating for a purer new form of art, divorced from objective representations, Kandinsky urged painters to imitate music’s employment of rhythm and abstract construction, to repeat notes of color and set them in motion. He also argued that pure abstract compositions, lacking objective imagery, should be anchored by small compositions that may appear meaningless and antagonistic to each other, but their opposition and lack of cohesion would harmonize the whole painting. He called the subordinate compositions melodic, and the compositions consisting of various forms, symphonic. Both would be linked by transitional forms, anchored by an undetectable non-geometric harmony, arising from a seemingly unintentional selection of shapes that appeal less to the eye, and more to the soul.

Another early influence on her practice were the writings of the 19th-century color theorist Charles Blanc, which inspired figurative Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, and the Neo-Impressionist (the separation of colors into individual dots or patches that interact optically) and Pointillist (painting tiny distinct dots next to one another in order to form an image) movements. Discernible in Zeid’s mid-abstract period are Blanc’s ideas on the separation of colors into individual patches. With Zeid, they do not interact to represent a figurative scene, but aggregate in a pulsating multicolor abstract murmuration.

Fahrelnissa Zeid standing in front of her painting Vers un Ciel (Towards a Sky) exhibited at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (image courtesy of Fahrelnissa Zeid Estate; photo: Studio Yves Hervochon, 1953)

Towards a Sky exemplifies these effects in its oppositional permutations of color eddies and shards. When seen horizontally, as the work is sometimes displayed, there is no discernible center or recognizable composition across its maximalist surface, but a powerfully felt symphonic motion. Displayed vertically, an invisible but perceptible movement pulls the disparate chromoluminarist melodies upwards.

The title of the work leads the viewer to focus on the blue concentration at the top (or to the right, when the painting is displayed horizontally). The eye then wanders back and forth from there to the bottom (or left) yellow ensemble. However, Zeid did not tend to give literal titles to her works, so this painting’s upward dynamic may well evoke Kandinsky’s notion of how the spiritual life of humanity is comparable to a pyramid progressing imperceptibly towards the future, with artists leading humanity on that path.

Zeid usually outlined her paintings by drawing an almost continuous line in charcoal pencil, then sketching the interstitial honeycombs, and finally filling them up with a limited range of colors. Here the palette comprises the primary colors: red, yellow, and blue, complemented by a few secondary and tertiary colors, with whites and blacks in between.

Fahrelnissa Zeid, Towards a Sky, 1953, oil on canvas, 593 x 201 cm (private collection; photo: Sotheby’s, 2017) © Fahrelnissa Zeid Estate

Visual analysis

Although the painting is meant to be viewed vertically, we can analyze its interweaving of colors and shapes horizontally from the left, to follow the manner in which Zeid herself created the work, as she painted her larger canvases by tacking them along the walls of her studio; the left side of the painting is also where the most defined shapes are drawn.

Leaning towards the left is a sloping yellow peninsula. The edge of its roughly shaped triangle is followed by an almost imperceptible concentric vortex dominated by smaller white and green shards interspersed with maroon, pink, and blue spikes and triangles. Transitioning onto the last subdivision on the right is a vertical stack of maroon, black, and blue oblongs, delineated by a narrow white barrier of white shards. The painting ends on the right with a multiplicity of diffused floating shapes. The gap between the first triangular ensemble and the central vortex is filled by a transitional spill of mainly white, blue, and maroon trapezes and convex rectangles. When seen vertically, however, the painting reveals its irresistible dynamic: a spiraling path upwards from an ascending yellow slope, moving through a concentric greenish implosion, across a step and onto a floating azure arrangement of broken shards.

This dynamic perfectly aligns with the artist’s description of her practice as a quest for salvation and a communion with the universe. She stated that her paintings surged within her from depths “far beyond peculiarities of sex, race or religion.” When working, she would feel “as if the sap were rising from the very roots of [a] Tree of Life to one of its topmost branches, where I happen or try to be, and then surging through me to transform itself into forms and colors on my canvas. It is as if I were but a kind of medium, capturing or transmitting the vibration of all that is, or that is not, in the world.” [1]

Bridging universes

Born in 1901 into a family of intellectual and artistic Ottoman state officials, the young Fahrinnisa Şakir Kabaağaçli was in 1919 one of the first students to attend the Women’s Academy of Fine Arts, Istanbul, in modern-day Turkey. She quit after marrying, however, and travelled frequently with her writer husband İzzet Melih Devrim to visit European museums. In 1928, she joined the Académie Ranson in Paris, which led her to abandon her academic figurative style and adopt an expressionist style. Upon her return, she re-enrolled at the Istanbul art academy.

After getting divorced, she remarried the Iraqi diplomat Prince Zeid bin Hussein and adopted his first name for her last name, and Arabized her first name (from Fahrinnisa to Fahrelnissa). She suffered in the following few years from physical ailments and mental breakdowns, and doctors advised her to focus on her art to feel better. Zeid would later credit painting for saving her life.

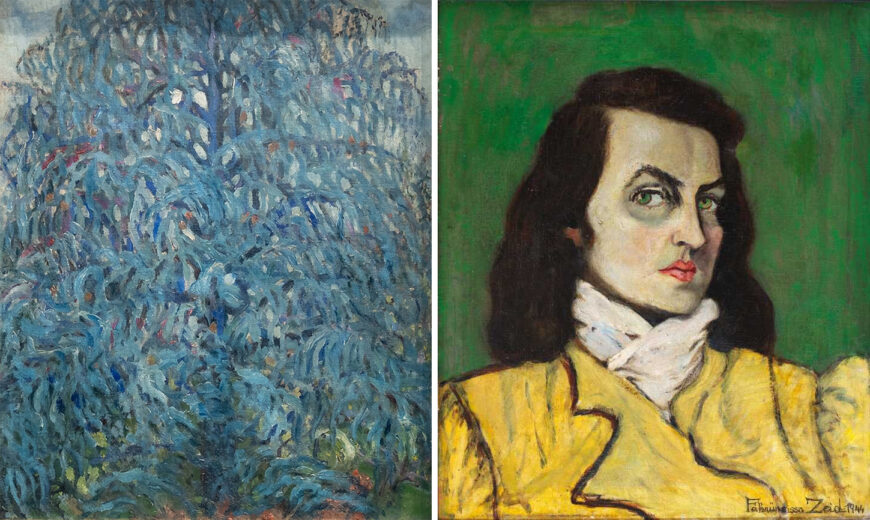

Paintings from Zeid’s time in Istanbul during World War II. Left: Fahrelnissa Zeid, The Blue Tree, 1943, oil and gouache on canvas, double-sided, 54 x 45 cm (private collection; photo: Sotheby’s) © Fahrelnissa Zeid estate; right: Fahrelnissa Zeid, Self-Portrait, 1944, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm (Sema-Barbaros Çağa Private Collection) © Fahrelnissa Zeid estate

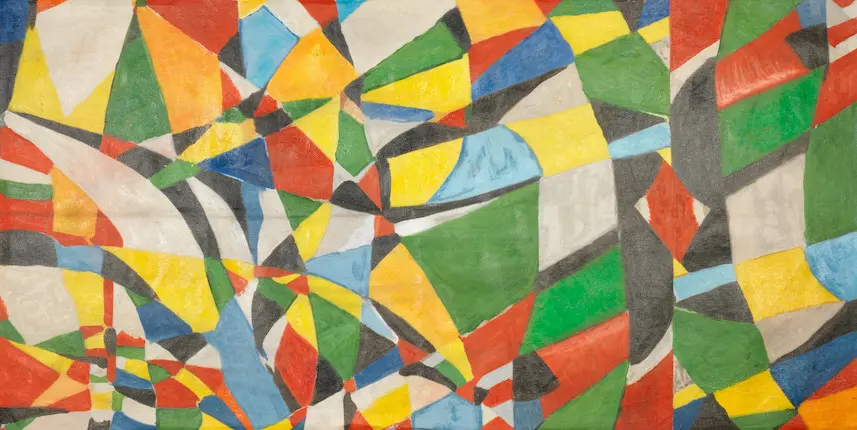

Fahrelnissa Zeid lived and traveled between Europe and Baghdad in the 1930s, busy with her family and social obligations, and took private painting lessons all along. She returned to Istanbul during World War II and focused on her work, painting expressionist portraits, nudes, cityscapes, symbolist scenes, and busy flat perspective interiors in saturated colors, thick impastos, black contours, and tightly controlled small motifs. She joined a local modernist art collective called D Grubu in 1941, becoming their only Turkish female member. She began exhibiting alone in 1945 to critical and commercial acclaim. She complained, however, of being dismissed as an amateur by some of her male peers, and she longed to affirm herself artistically beyond Istanbul.

Fahrelnissa Zeid in her London studio painting Le Voyage de l’Homme lune (Voyage of the Man Moon), 1949 (image courtesy of Fahrelnissa Zeid Estate)

Soon after the war ended, Zeid left for London where her husband was appointed as ambassador. She ended up living between Paris and London for three decades and exhibited in both cities regularly. She adopted abstraction in 1949 after undergoing a sensory shock on her first intercontinental flight, looking over receding fields below. In 1952, she joined a new group of painters and critics known as the Nouvelle École de Paris.

Her abstract period went through distinct phases that began with an experimental period of aerial views of geometrically abstracted agricultural fields, traversed by swirling black lines. She then transfigured her terrain abstractions into large and monumental polychromatic murmurations, like Towards a Sky.

No limits

Fahrelnissa Zeid’s fifty years practice would undergo numerous stylistic transformations, but her works are recognizable for their Fauvist color choices and exhilarating juxtapositions; expressionist brush application and intense palette knife incisions; pulsating black lines, all-over fragmentation of planes, small jarring motifs; and, often, her signature ambitious scale.

Well into her last years, she continued to paint, draw, paint on unexpected media like sea rocks and poultry bones, explore new materials such as colored resin sculptures and stained glass, and she also returned to portraiture. All this, despite undergoing the tragedy of the killing of her husband’s entire family in the 1958 Iraqi republican revolution, which drove them into exile for more than a decade and led her to suspend her practice. She passed away in 1991, in Amman, Jordan, where one of her children settled, and where she taught art for a decade to a new generation of abstract artists.

Fahrelnissa Zeid’s drive yielded an innovative and prolific output despite numerous challenges. She was able to deploy considerable energy to produce works requiring great focus, while also exploring new styles in rapid sequence. Her maximalist abstract expressionist works evoke the sublime with their teeming, unleashed power. Her sublime was a projection of the exaltation she described feeling while working, and a transposition of her shifting moods. Her loss of self in painting is mirrored in viewers’ own submersion in the shapes, colors, and movement of her works.

Describing her painting process, Fahrelnissa Zeid could well have described Towards a Sky: “painting is for me, flow, movement, speed, encounters, departures, enlargement that knows no limits.” [2]