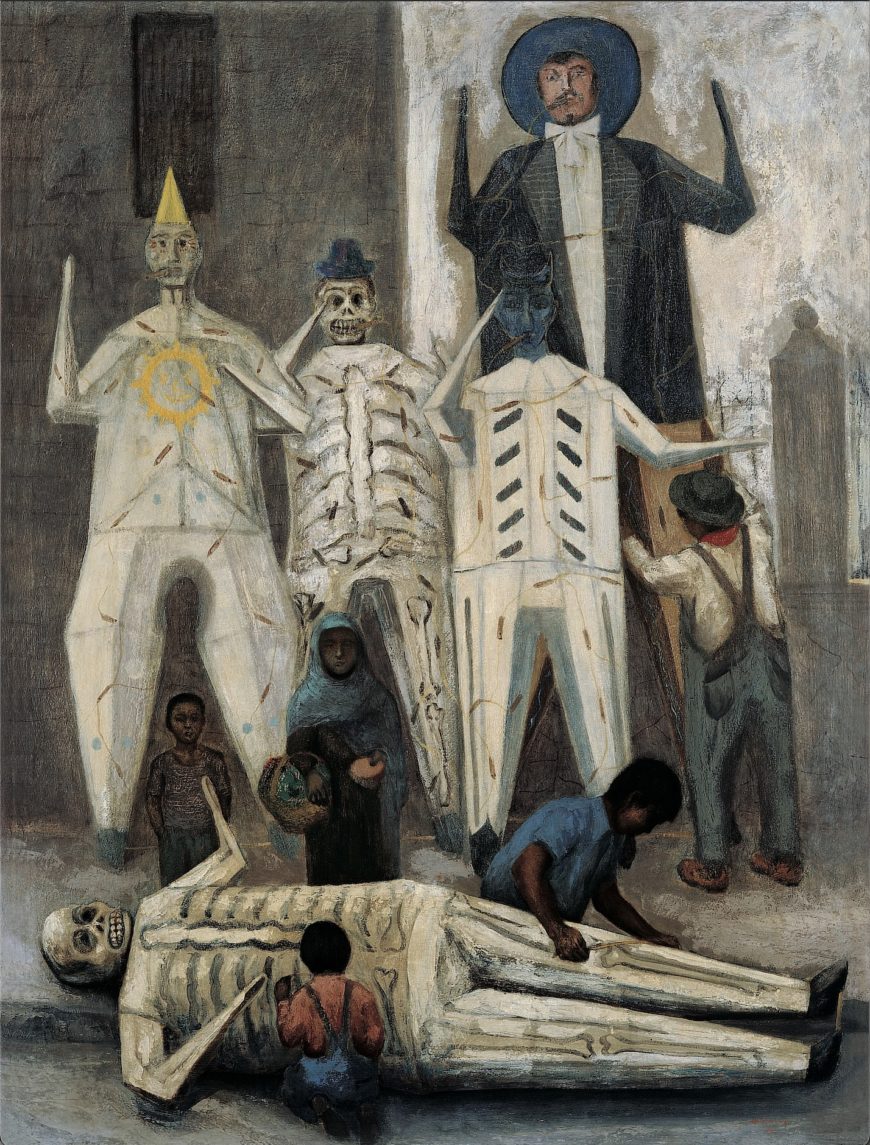

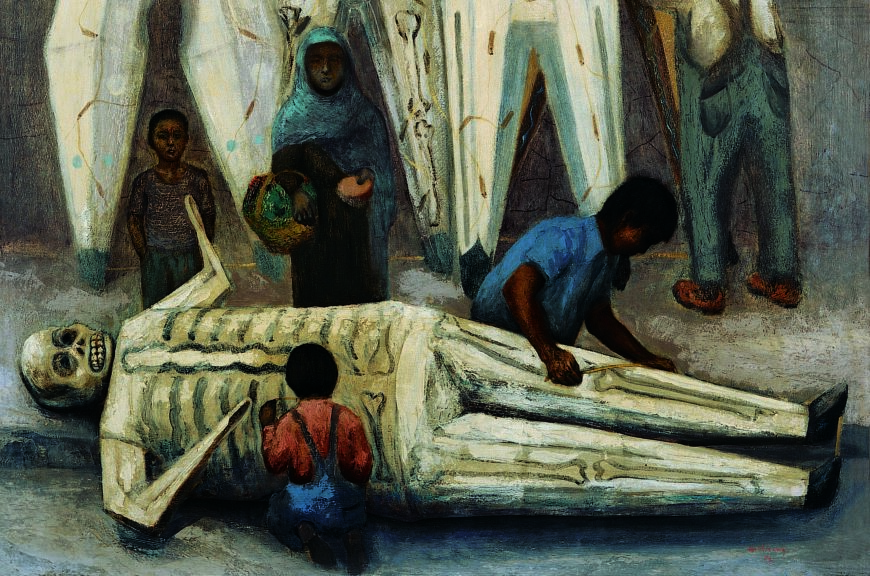

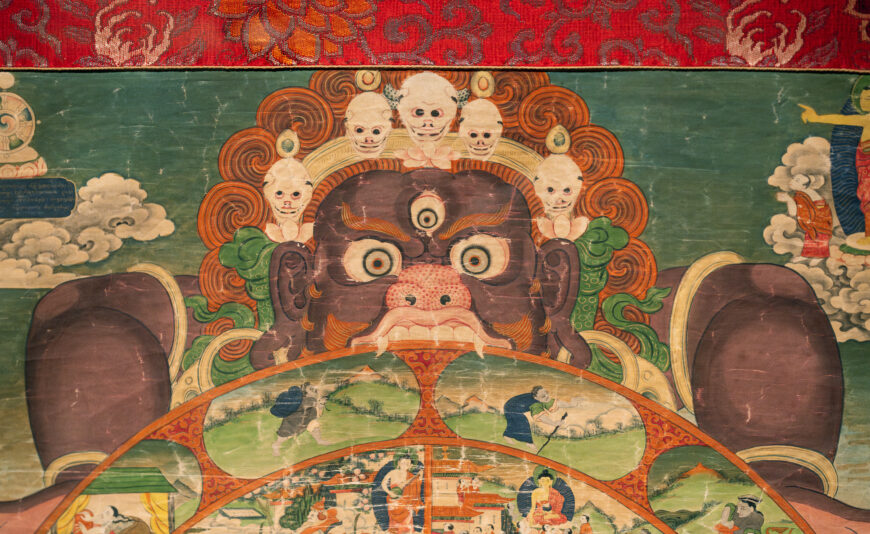

At first glance, if one is unfamiliar with Mexican popular culture, this painting may cause some bewilderment. What are the oversized skeletons doing? Who is the giant, stiff figure in the background? This artwork, titled Los juderos (The Judas Figures), was painted by the Japanese Mexican artist Luis Nishizawa in 1952. The unique subject is a product of cultural encounters—it depicts the Mexican custom of constructing large scale papier-mâché Judas figures to commemorate the biblical story of Judas. The creation and the subsequent burning of the papier-mâché figures that represent Judas (the apostle that betrayed Christ) are symbolic of religious purification and rejuvenation. Its intriguing subject matter reflects a Christian Easter ritual that was transformed into a popular Mexican tradition. Playing with proportion and scale to depict the scene, Luis Nishizawa creates a work of art that makes what is traditional modern, and what is European in origin, Mexican.

The volcano Iztaccíhuatl (White woman) is on the left, recognizable by the shape of a sleeping woman and Popocatépetl (Smoking mountain) is on the right. Luis Nishizawa, Sunset, c. 1990, suiboku ink on paper, 37 x 73 inches

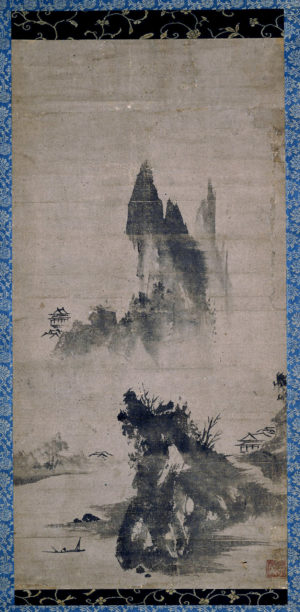

Nishizawa’s landscapes (discussed more below) also demonstrate cultural encounters, synthesizing Japanese aesthetics with a Mexican subject. In the 1960s, Nishizawa began to focus on painting the Mexican countryside as he traveled around the country, recalling his early childhood memories and his personal and spiritual connections to the natural world. In Sunset, Nishizawa utilizes suiboku (also called sumi-e ink) to depict the Valley of Mexico. The Japanese art of sumi-e combines calligraphy and ink painting to show gradations contrasting density and lighting, and is one that he used often in landscape paintings.

Nishizawa’s work conveys the convergence of the diverse cultures that constitute what it means to be Mexican. Many Mexican modernists like Nishizawa were keen to represent Mexican culture, traditions, and landscapes as a way of expressing national identity. The term mexicanidad (Mexicanness) describes this endeavor and reflects what it means to be Mexican embracing Mexican history, traditions, and culture. For the modernists, it was important to distinguish themselves from the Mexican elite society that had so often emulated European culture in the past. Nishizawa’s understanding of mexicanidad was complicated and enriched by his mixed-race background. For Nishizawa, mexicanidad encompassed the confluence of many cultures, not just European and Indigenous, but also Asian. Nishizawa’s genre and landscape paintings demonstrate various facets of these cultural convergences. This is reflected in his choice of subject matter as well as artistic materials.

Mestizaje and modernism

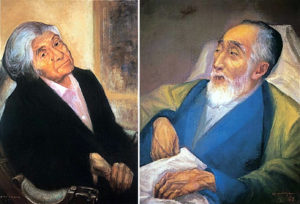

In family portraits from 1965 and 1967, Nishizawa depicts his aging parents with tenderness and simplicity. Luis Nishizawa, Mi madre (left), 1967, mixed media on canvas and wood, 70 x 48 cm; Mi padre en sus largos dias (right), 1965, mixed media, 64 x 51 cm

Nishizawa was born in Mexico to a Japanese father and Mexican mother. Relations between Japan and Mexico date back to the 1610s, when Japanese missions were sent to colonial New Spain (which included present-day Mexico) via the Manila Galleons (Spanish trading ships that sailed from the Philippines to the New World). Though a small number of Japanese settled in New Spain in the 17th and 18th centuries, it was not until the 19th century when more widespread migration of peoples occurred from East to West prompted by an opening up of trade and commerce. The first real phase of Japanese migration began during the Meiji era (1868–1912) when Emperor Meiji transformed the country from an agrarian economy to one that was industrial and capitalist.

Luis Nishizawa’s father, Kenji Nishizawa, arrived in Mexico in 1908 during this period, just a few years before the Mexican Revolution (1910–20). He soon married Luis’s mother, María de Jesús Flores, and the couple settled in San Mateo Ixtacalco, Mexico where Luis was born.

Nishizawa moved to Mexico City as a young boy and later trained at the Academy of San Carlos in the 1940s alongside the Mexican modernists, such as José Chávez Morado, Julio Castellanos, and Alfredo Zalce. He embraced the Mexican modernists’ passion for representing local customs and traditions in innovative ways. In his early career, Nishizawa admired the political spirit of the Mexican muralists, such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, and was captivated by social realism. Social realism is a term used to describe artwork that represents the socio-political conditions experienced by the working classes. Social realists were critical of the power structures that enabled and sustained social and racial hierarchies. For example, in Los Juderos, Nishizawa purposefully portrays the Indigenous artisans industriously constructing the effigies emphasizing the labor behind the tradition, not the fanfare of the ceremony itself.

The Burning of Judas

Nishizawa’s Los juderos celebrates the popular Mexican transformation of a European Christian ritual. Nishizawa met the famous Mexican muralist Diego Rivera while shopping for Judas figures at the Mercado Abelardo Rodríguez, a traditional public market. Both Nishizawa and Diego Rivera were fascinated by the Burning of Judas tradition and had a mutual respect for each other’s work. Today, visitors can see Rivera’s collection of Judas and Calavera figures at his former house and studio that he shared with his wife Frida Kahlo, now known as the Museo Estudio Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

The Burning of Judas ceremony is celebrated at Easter when effigies of Judas Iscariot are burned. Judas Iscariot was a disciple of Jesus Christ and one of his twelve apostles. According to the New Testament, Judas betrayed Christ, which led to Christ’s Crucifixion. The Burning of the Judas effigies is a symbol of cleansing oneself of evil and starting anew spiritually. The ritual is practiced in many Christian countries around the world although specific traditions have developed unique to distinct countries and cultures.

The “Quema de Judas,” as it is known in Mexico, is a particularly special event that dates to Spanish colonization. It was used as a tool to evangelize the Indigenous people, representing the triumph of good over evil. The tradition may also have origins in the executions during the Spanish inquisition that sought to eradicate heretics (people who did not conform to Catholicism). The ritual takes place on Sábado de Gloria or Holy Saturday, the Saturday before Easter Sunday. Initially, Judas figures were created out of hay and rags and then burned. Later, as new materials became available, the Judas figures were built out of cardboard and papier-mâché and stuffed with fireworks. They were paraded throughout towns, hung in public plazas, and burned to much fanfare. Other effigies besides Judas, such as devils, skeletons, and even political figures, were also constructed. This lively tradition continues to this day where artisans compete for the best Judas figures and theatrical reenactments of the biblical story are performed throughout Mexico.

In Los juderos, Nishizawa portrays five Judas effigies, including four oversized skeleton figures with masked faces and a large male figure, in the background. Three of the skeletons are standing upright, while the fourth is laying on the floor. Although the four oversized skeletons in Los Juderos share affinities in their body shapes and stiffness, Nishizawa gives them unique features, diverse masked faces, hats, and design details. The composition stands out for the varying and disproportionate scales of the figures. Although oversized themselves, the Judas skeletons are overshadowed by the enormous Judas figure in the background who mimics their rigid poses and saluting arm gestures. The standing Judas gazes directly outwards, inviting the viewer into the composition. The smallest figures are the Indigenous people working on the effigies. A mother and child walk among the them and seem to share the viewer’s role as spectators. The other three Indigenous figures are portrayed in action, bending over, fixing, and attending to the making of the effigies. Nishizawa honors their artistry by including them in the scene. By depicting the Mexican workers in the act of building the effigies, Nishizawa highlights the labor behind the tradition, a subject that had often been invisible and unrecognized, and was an important social realist theme.

The turn to the Mexican landscape

Luis Nishizawa, Sunset, c. 1990, suiboku ink on paper, 37 x 73 inches

In addition to genre paintings with social realist themes, Nishizawa also painted portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. He was outspoken about his mixed heritage, and the diverse cultural influences present in his work. Despite having a Mexican mother, being raised on a Mexican hacienda, and having studied at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City, Nishizawa was especially impacted by Japanese aesthetics and artistic techniques. He spoke frequently of how much he revered his Japanese father and how his father affected his artistic outlook. In the 1960s, Nishizawa traveled to Japan and worked with Japanese artists. He experimented with and embraced various Japanese artistic methods, such as ink wash painting and calligraphy. In the many art forms that he worked, including drawing, painting, printmaking, and ceramics, Nishizawa combined antique and modern elements, Indigenous, European, and Japanese techniques.

Dr. Atl, View of Popocatepetl, 1934, tempera and atl color on masonite, 100 x 125 cm (Colección Blaisten)

In the 1960s, Nishizawa turned to representing Mexico’s countryside, producing a large body of landscapes. Important influences include the 19th-century landscape painter José María Velasco and the 20th-century modernist, Dr. Atl. In several of his landscapes, such as Sunset, Nishizawa features the two volcanic mountains of Popocatéptl (Smoking Mountain) and Iztaccíhuatl (Sleeping or White Woman) which overlook the Valley of Mexico. The tragic love story of Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl is sometimes referred to as the Aztec Romeo and Juliet. Aztec legend has it that the princess Iztaccíhuatl fell in love with one of her father’s warriors, Popocatépetl, but her father was against their marriage. Popocatépetl was sent away to battle and while fighting, Iztaccíhuatl was given the false news that Popocatépetl had died. Upon hearing this terrible news, she died of grief. When Popocatépetl returned to the village and found that Iztaccíhuatl had died of a broken heart, he buried her body on the great mountain surrounding the valley. He then knelt beside her and also died of sadness. The gods touched by the young couple’s love for one another, turned their bodies into volcanoes. Iztaccíhuatl’s mountain is sometimes called Sleeping Woman or White Woman because the shape of the mountain resembles a reclining woman and is often covered in snow. Popocatépetl’s mountain is called Smoking Mountain because it regularly emits smoke to show he is still watching over his beloved. Together they are a symbol of everlasting love and mexicanidad.

Monochrome landscape. Sessō Tōyō, Haboku-style landscape, hanging scroll, 15th century, Muromachi period, Japan, 63.5 x 31.7 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

In utilizing sumi-e (ink painting) to create this landscape, Nishizawa emphasizes brushwork and texture. He creates the soft mountain peaks without firm outlines, instead contrasting brushstrokes, from gentle to rugged, to convey powerful expression. Sumi-e painting is a contemplative art form based on the principle that less equals more. It is a highly regarded Japanese painting style as the artist requires adept technical skill to control the brush and maintain the delicate balance between water and ink. The practice is demanding and meditative, necessitating discipline, persistence, and imagination. Departing from a traditional sumi-e monochrome black ink palette, Nishizawa infuses the composition with translucent blues and greens, invoking the Mexican valley’s essence and vitality.

Commitment to his communities

Nishizawa consistently and thoughtfully portrayed Mexican culture and traditions, such as juderos and Mexico City’s volcanic mountains, throughout his lifetime. At the Museo-Taller Luis Nishizawa, the museum dedicated to Nishizawa that was founded in Toluca, Mexico in 1992, museum staff continue to hold Judas competitions and actively participate with the community in parades throughout the city. The Burning of Judas ceremonies are important Mexican rituals that are still celebrated with great passion and fervor today. Until Nishizawa’s death in 2014, the jury that evaluated the Judas effigies was led by the artist himself, demonstrating his commitment to popular traditions and his community.